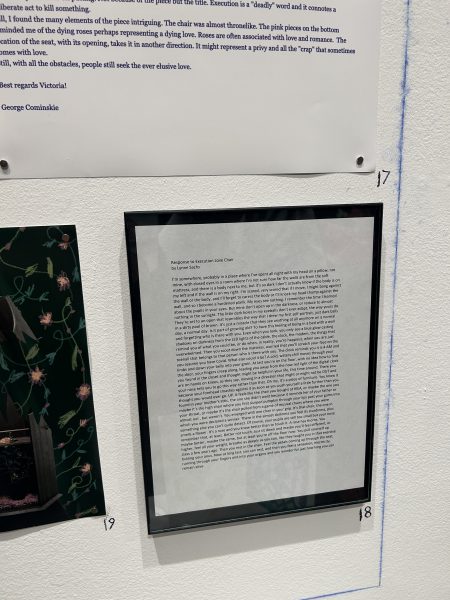

Assignment: Respond to this photo without any details.

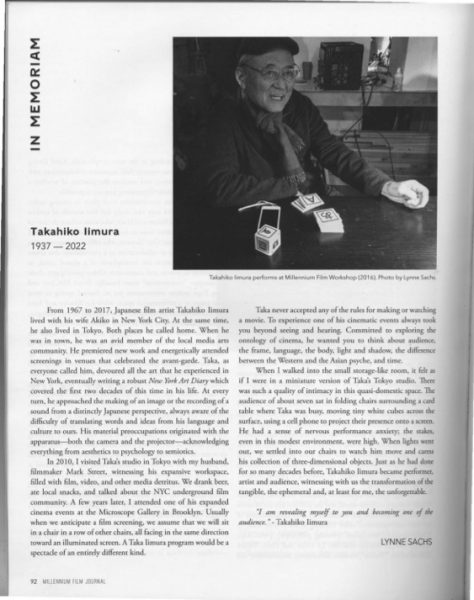

This is Not How I Imagine It But How It Is

Lynne Sachs, July 15, 2023

This is not how I imagine it but how it is. I’m somewhere, probably in a place where I’ve spent all night with my head on a pillow, not mine, with closed eyes in a room where I’m not sure how far the walls are from the soft mattress, and there is a body next to me, but it’s so dark I don’t actually know if the body is on my left and if the wall is on my right. I’m scared, very scared that if I move, I might bang against the wall or the body, and I’ll forget to caress the body or I’ll knock my head thump against the wall, and so I become a hardened plank. My eyes see nothing. I remember the time I learned about the pupils in your eyes. But mine don’t open up in the darkness, or reduce to almost nothing in the sunlight. The little dark holes in my eyeballs don’t ever adapt, the way yours do. They’re set to an open that resembles the way that I drew my first self-portrait, just dark balls in a dirty pool of brown. It’s just a miracle that they see anything at all anymore on a normal day, a normal day. Is it part of growing old? To have this feeling of being in a bed with a wall and forgetting who is there with you. Even when you look, you only see a blue glow casting shadows on darkness from the LED lights of the cable, the clock, the modem, the things that remind you of what you could be, or do when, in reality, you’re happiest, when you are just overwhelmed. Then you scoot down the mattress, worried that you’ll scratch your face on the toenail that belongs to that person who is there with you. The clock reminds you it is 4 AM and you assume you have Covid. What else could it be? A cold, watery chill moves through your limbs and down your belly into your groin. At last you’re on the floor, with no idea how to find the door, your fingers creep along, leading you away from the now red light of the digital clock you found in the closet and thought might be helpful in your life, this time around. There you are on hands on knees, as they say, moving in a direction that might or might not be OUT and your nose tells you to go this way rather than that. Oh my, it’s a piece of furniture. You know it because your forehead smashes against it as soon as you push yourself a little further than you thought you would ever go. UP. It feels like the chair you bought at IKEA, or maybe the one you found in your mother’s attic, the one she didn’t want because it reminds her of your father or maybe it’s the high chair where you first slurped pumpkin through your lips past your gums into your throat, or maybe it’s the chair pulled from a game of musical chairs where you were almost out , but weren’t. You emerged with one chair in your grip. It’s that chair, the one in which you were declared a winner. There in the almost darkness you feel its sturdiness, plus something else you can’t quite detect. Of course, your pupils are still too small but your nose smells a flower. It’s a rose and you know better than to touch it. A rose has thorns. You remember that, at least. Better not touch. Just sit down and maybe you’ll feel different, or maybe better, maybe the same, but at least you’re off the floor now. You pull yourself up higher, feel all your weight, breathe as deeply as you can, like they taught you in that exercise class a few years ago. Then you rest in the chair. Feel the petals coming up through the seat, tickling your anus. Now at long last, you can rest, and then you feel a sensation, electricity, running through your fingers and into your organs and you wonder for just how long you can remain alive.

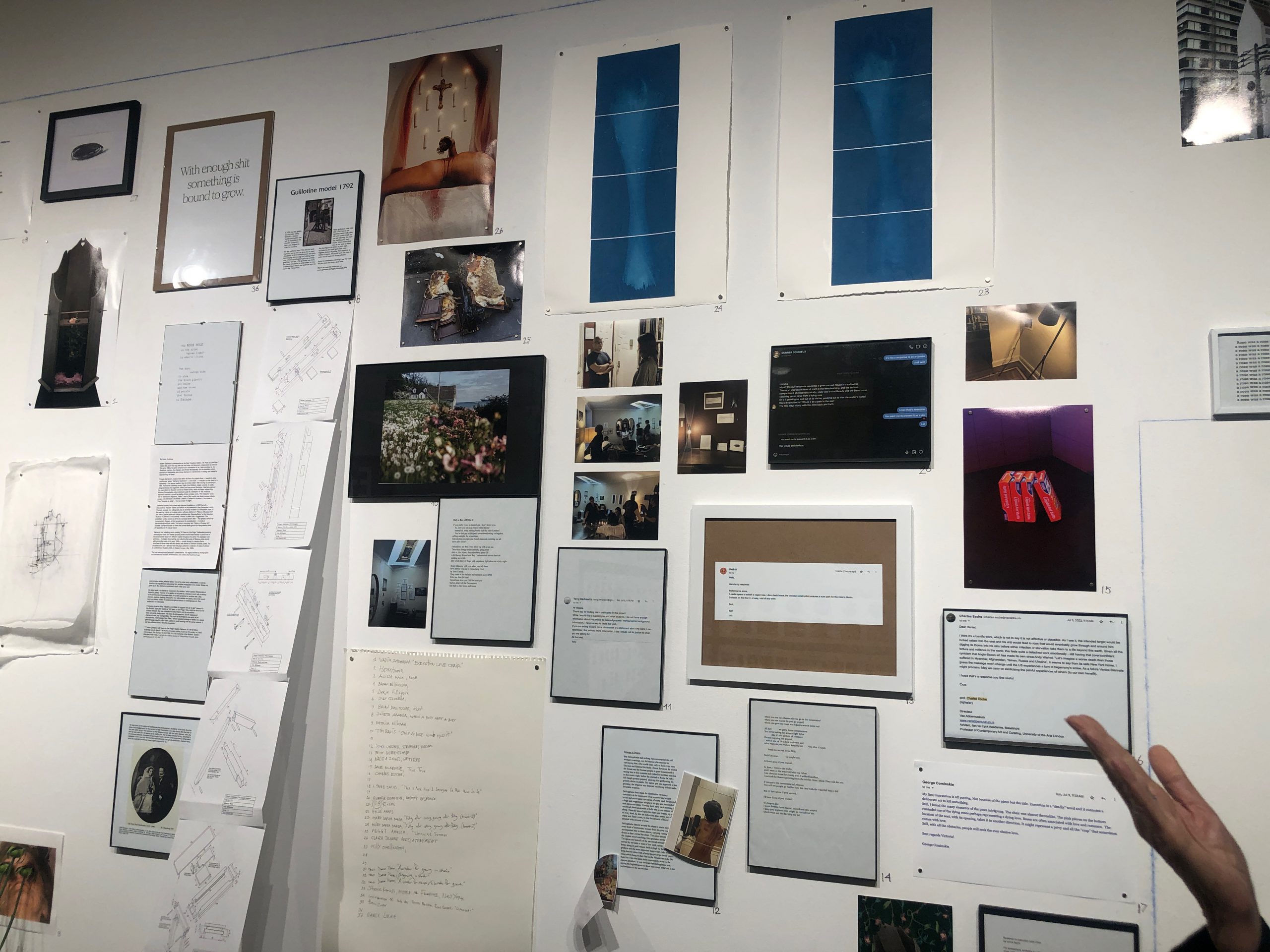

Distortions: Moscow Conceptualists Working Today

September 9 – October 28, 2023

https://www.205hudsongallery.org/calendar/2023/8/22/distortions-moscow-conceptualists-working-today

Hunter College Art Galleries: 205 Hudson Gallery

205 Hudson Street

New York, NY

Hours: Tuesday–Saturday, 12-6pm

Curated by Hunter College Professors Daniel Bozhkov and Joachim Pissarro with Dr. Olga Zaikina and Graduate Curatorial Fellow Victoria Borisova

Exhibition

Moscow Conceptualism began as an alternative underground art world in the late Soviet Union. Its unofficial status shaped its artistic methods and theoretical framework. The exhibition includes original objects, archival materials, and working models of original artworks, alongside new projects created by Moscow Conceptualists in collaboration with art and art history students and faculty at Hunter College. Thus, Distortions is an experiment in intergenerational and cross-cultural collaboration. It aims to transform the gallery into a two-month long forum exploring how existing artworks can be activated to create new living situations, and how documents can be used beyond the preservation of the past.

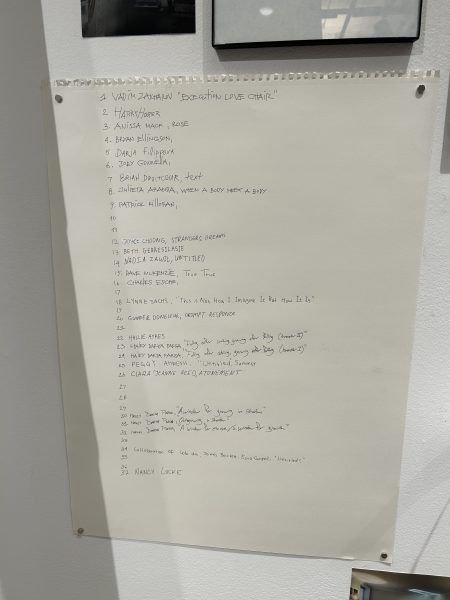

Participating artists and art groups:

Yuri Albert (born 1959 in Moscow, lives and works in Cologne)

Collective Actions (active 1976-present)

Gnezdo (active 1974-79)

Sabine Hänsgen (born 1955 in Dusseldorf, lives and works in Bochum, Germany)

Andrei Monastyrski (born 1949 in Pechenga, Russia, lives and works in Moscow),

Victor Skersis (born 1956 in Moscow, lives and works in Bethlehem, PA)

Nadezhda Stolpovskaya (born 1959 in Moscow, lives and works in Cologne, Germany)

SZ Group (active 1980-84, 1989, 1990)

Vadim Zakharov (born 1959 in Dushanbe, Tajikistan, lives and works in Berlin, Germany).

Distortions: Moscow Conceptualists Working Today was developed through a two-semester graduate curatorial seminar at Hunter College led by professors Daniel Bozhkov and Joachim Pissarro with Dr. Olga Zaikina. It included studio art students: Lauren Cline, Tucker Claxton, LeLe Dai, Paula De Martino, Alicia Ehni, Stevie Knauss, Milly Skelington, Johnny Sagan; and art history students: Caitlin Anklam, Victoria Borisova, Jay Bravo, Andrea Dauhajre, Curtis Eckley, Daniel Kuzinez, Jake Robinson. Visiting scholar: Virginia Marano, PhD Candidate, University of Zürich, Switzerland.