Wanting to Get Closer: Traveling through History with a Bolex

MoMA Magazine

By Lynne Sachs, Sofia Gallisá Muriente, and Sophie Cavoulacos

August 9, 2023

https://www.moma.org/magazine/articles/936

Wanting to Get Closer: Traveling through History with a Bolex

Two filmmakers explore the connections between their work decades apart in Vietnam and Puerto Rico.

Sofia Gallisá Muriente, Lynne Sachs

Aug 9, 2023

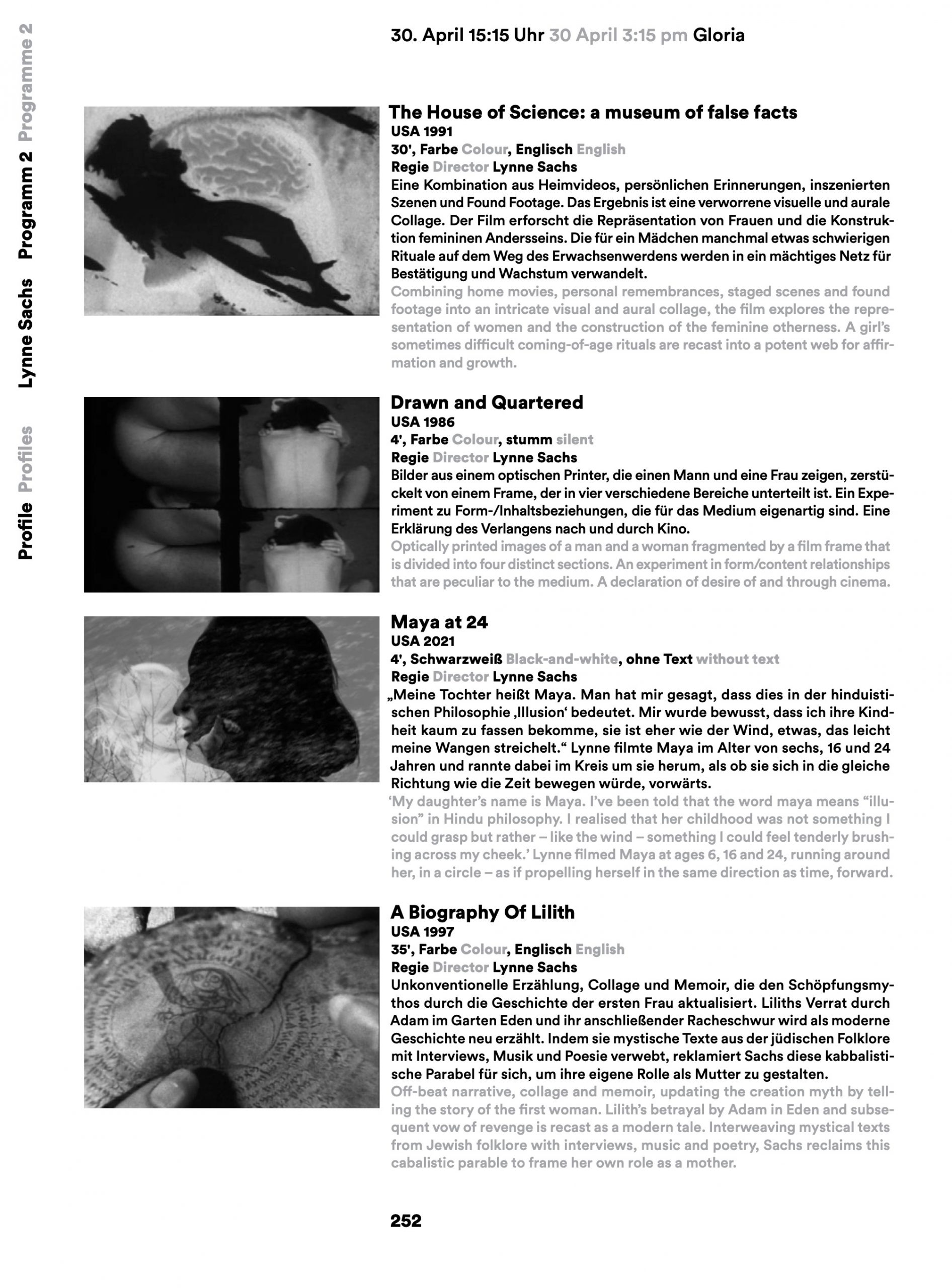

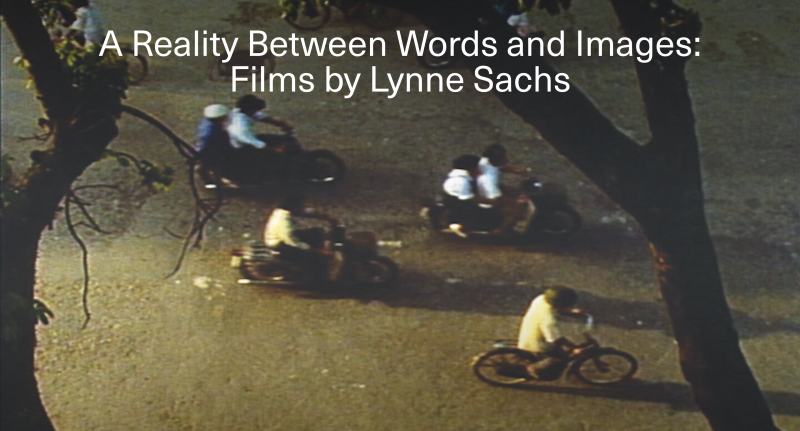

Lynne Sachs and Sofia Gallisá Muriente first met in the classroom over a decade and a half ago, and have been collaborators and interlocutors ever since. Sachs’s Which Way Is East: Notebooks from Vietnam (1992) was recently restored by MoMA, and Gallisá Muriente’s Celaje (Cloudscape) (2020) recently entered the Museum’s collection. As part of our summer of screenings drawn from the collection, they reflect on the pairing of their films kicking off the series Here and There: Journeying through Film on August 16 with a special screening in MoMA’s Sculpture Garden.

—Sophie Cavoulacos, Associate Curator, Department of Film

Sofia Gallisá Muriente: It’s such a beautiful opportunity to think of these two films in relation to each other. It’s not a combination I would have foreseen but it is obvious to me now that there are so many connections.

Lynne Sachs: I’ll start with the idea that these are both 16mm films, and that goes beyond the look of them. It has to do with the way that our bodies engage with the camera, a sensibility. I will say as a backdrop to making Which Way Is East, which I shot in 1992 in Vietnam, that video was fully available. It was extremely challenging to have access to Vietnam as an American. At that time the country had really just opened up. Having a video camera would have given me so much more time to explore with the camera running. Yet there was something about taking my Bolex camera, knowing that I would have to slow down, have a relationship with the light, record sound separately so my listening had to be really sharp. My travel load was much heavier carrying all that film in my backpack. It shifted the trip to be about observation and not about acquisition.

SGM: I’m thinking back on how I came to begin what is now Celaje (Cloudscape), which I started as my thesis project.

LS: In the film you say, “I wanted to make a film about my grandmother and the distance between her memories and my reality.”

SGM: Yeah, I had all these letters written by my grandmother, and I was filming with her in spaces that had to do with her life story. But the present reality of those places was so distant from the memories that she had that I felt like the film was a negotiation between her stories and my way of seeing her in those spaces. Time went on and I kept being interested in filming her and the ways in which I saw her life story as emblematic of, or embodying in some way, the larger narratives of Puerto Rico’s history.

I have a very strong memory of watching Which Way Is East in your class, and having that be part of finding my own voice, how I felt I could be making films. But obviously the big difference between our films is that I’m traveling through my own country and you’re traveling through Vietnam. You’re in Vietnam looking for how you are implicated in that history, for your country’s implication in that place. I love that line in the beginning, where you say, “My mind is full of war, and my eyes are on a scavenger hunt for leftovers.”

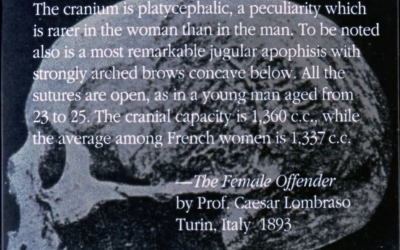

LS: In both of our films there are ghosts. For my generation, it’s the ghosts and the tragedy of war—what people from the United States called the Vietnam War, and what people in Vietnam call the American War—and the stories that were left untold. One thing I learned from making Which Way Is East is how important it is to become aware of what you’ve been taught about that place, the narratives that have insisted that we imagine it a certain way.

I tried to hearken back to lying on a couch and looking at the Vietnam War through black-and-white images, Walter Cronkite on the evening news, and whatever he said came with authority, and the images also came with authority.

SGM: That’s the very first line of the film, about how you would lie on the living room couch and watch the news upside down. It’s such an intimate, relatable moment. And at the same time, you’re already hinting at the fact that you would become a filmmaker, and that part of what you do in the world is to turn things on their side, or look at things from a different angle in order to gain some other understanding of them.

I had this footage that I had shot for the thesis film and abandoned. But then I started making a film in 2019 that for me was about the trace of all of these disasters that had happened. Around the moment when Hurricane Maria was happening, the earthquakes were happening, the protests were happening, the debt crisis was happening. One thing that I was clear about was that I didn’t feel compelled or interested in going out with a high-definition digital camera to make beautiful images of what was destroyed, or people suffering. I had just recently been gifted the Super 8 camera, and it was so light and automatic and easy.

But time passed, and you realize how quickly nature erases the trace of certain things. In the tropics especially, everything is always rotting, vegetation is always taking over. I wanted to make a film about the accumulation of traces of all of these different political processes and natural disasters.

LS: Right smack dab in the middle of Celaje you say, “I heard someone say there is no paradise without debt.”

SGM: I heard someone say that at a bar! It’s a take on a famous line from a salsa song that says without salsa there’s no paradise.

LS: And you have this shot down the main highway of San Juan leading to where all the big hotels are, but you don’t concede that, you won’t give in to those beautiful beaches.

SGM: Paradise is a construct built for tourism, right? And for a tourist gaze that is very superficial, you could almost switch one place for another as long as it’s a beautiful beach with palm trees. I think our films are also about challenging that superficial view and learning to see deeper. In your film, as a tourist in Vietnam, and even in my film, I’m going to film in places outside of San Juan that for the most part I have only experienced from a car. There are areas of the country where I think, I’ve never gotten out of the car in this town or in this neighborhood. This is a landscape that I’ve only seen from a highway, and what does it mean to slow down and actually get out of the car and get closer to things?

There’s a moment in the film where I’m in the salt fields in Cabo Rojo, with this pink water and mountains of salt. I almost didn’t include it in the film, because that’s such a well-known image in Puerto Rico. A very photographed, very visited place. But what blew me away was that someone explained to me that the Fish and Wildlife Service has to make sure that that salt field is commercially exploited, because even though it’s a natural reserve, they need to produce salt in order to sustain the ecosystem. The mineral extraction has been happening for centuries, for so long that the ecosystem depends on it.

And that just immediately changes how you look at that place. And since the film came out, because of erosion and earthquakes, that very site has been flooded with water and the salt farming is not happening as it should. We capture something with our cameras, and we have no idea how quickly it will change and how quickly that image will become a document of a past that we can no longer witness in person.

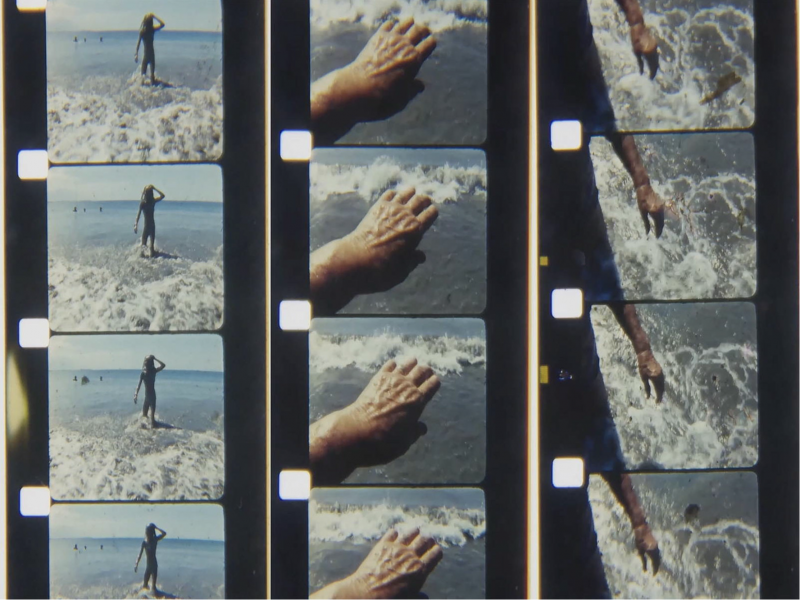

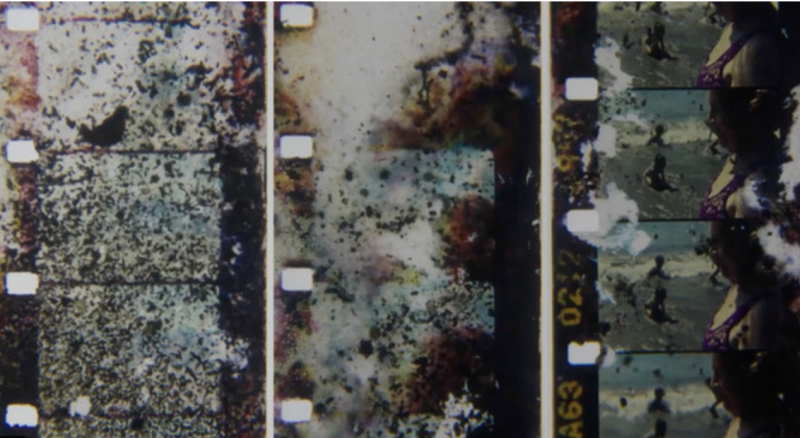

LS: Another way you work through that idea of impermanence is how you embrace the chemistry of filmmaking, not just to do it, to show off the sprockets. I felt that in your film you were dealing with the materiality of the medium. It is not digital, it will decay. It is affected by time, as the earth is, as the buildings in Puerto Rico have been. You know that there is a parallel between the material that you used and the land and the culture that you are exploring. The fragility of both what’s in front of the camera and what’s in the camera was very profound.

SGM: When Hurricane Maria happened I was really struggling in how I wanted to respond in my practice to what was happening. I felt like I had to reconsider how I wanted to relate to image making. I had all this film in my freezer, film I hadn’t shot and been wanting to work with for a long time, and suddenly it was decaying. Everything was decaying. Everything had been flooded. There was no power for a long time. It smelled like humidity everywhere. At the time I didn’t have a Bolex, so I couldn’t really work with the film that was rotting in my freezer, but I’d gotten deeply interested in biodeterioration and started playing with that. I started reading a lot about salt and collected salt from the fields we were talking about earlier in order to put my film in it. And the images of my grandmother on the beach that we shot together, I later buried those in her backyard. That ended up becoming a series of works of which Celaje is the final part. I was responding to a moment where climate was clearly conditioning memory and the survival of material evidence of history. Notions about conservation and preservation and archives that I had were really futile in the context of the tropics.

But then, at the same time, I was dealing with the death of my grandmother, of my father, sitting with grief and finding ways of processing: to be thinking about the country at the same time that I’m thinking about my family was a kind of affective approach to politics.

LS: We share this idea that making art is not completely separate from our lives—an osmosis of life into what could be a very hermetic space of filmmaking. I think that Sofia and I try to use the space of filmmaking to guide our lives.

In 1992, my sister Dana started living in Hanoi. The war had ended in 1975, but Americans had only recently been able to travel and live there. As a writer, she decided to immerse herself in the place so that she could describe the country as it was changing. She taught English, but also learned to speak Vietnamese. That same year, I traveled to Vietnam to visit her. I brought my Bolex 16mm camera, a backpack full of film, and an audio cassette recorder. We began our collaboration.

One of the things that happened when we were making Which Way Is East was that I realized that Dana and I see the world very differently. At first, that became kind of an overwhelming obstacle. She comes out of a storytelling background, while I come out of poetry and experimental filmmaking. That friction taught us something about our sensibilities. There’s a scene in Which Way Is East where I look up, and I see the light coming through this very large coil of incense hanging from a ceiling. We were inside a crowded temple and while I was filming I insisted that we wait for a long time until the light was just right. It was driving Dana crazy. She told me that for many years the government had discouraged the practice of religion and had recently loosened up. Now Vietnamese were returning to places of worship in great numbers. We were witnessing that change right there in the crowded temple. So, yes, you can look at the image and be awed by its beauty. But the beauty also speaks to something that’s been lost, and reveals how politics affect daily life in this very intimate way. An image that is aesthetically so-called “powerful” has its limitations unless there’s another layer underneath that helps you understand it in a deeper way.

After we shot the film, I came back to San Francisco. We didn’t have the Internet. Letters would take weeks and weeks if they arrived at all. But we were trying to write the voiceover sections at the same time, so she would write something, and then she would give it to a flight attendant who happened to be coming across the Pacific, and then they would give it to someone in a library, and then I would go pick it up. The world still felt really vast at that time.

SGM: I also do love that moment where you’re observing as a tourist but some people are also welcoming your gaze. It’s interesting how that offsets this constant wanting to speak about war that you have. What is there for you to encounter? I kept thinking about how I love all of these people that look straight into the lens and are smiling or posing. I think about the right to beauty that people in complicated contexts or who have been through experiences of violence have, because when we were talking earlier about this notion of paradise or the tourist gaze, I always wrestle with that a little bit. Yes, beauty needs to be complicated but at the same time, Puerto Ricans are very proud to live in a beautiful place, and we also love going to beautiful beaches and taking that photograph that is then used by the tourism department to sell the island. How do you hold both thoughts at the same time? How do you resist or complicate beauty while also claiming it as a value that you can also treasure, in a way, about the place where you are?

You’re constantly looking from inside to outside, looking from a balcony, looking through a window, looking from darkness, through a silhouette. In your framing, there’s this constant recognition in the film that you’re outside, but that you’re interested, that you’re curious, that you’re wanting to get closer.

Here and There: Journeying through Film is on view in MoMA’s theaters August 16–23. Sofia Gallisá Muriente’s work is also included in the current exhibition Chosen Memories: Contemporary Latin American Art from the Patricia Phelps de Cisneros Gift and Beyond.