Time and Light : Gunvor Nelson’s Vision of Editing

by Lynne Sachs

M a T e R i A L cinema

Issue #30 – Otherzine

Spring 2016

http://www.othercinema.com/otherzine/time-and-light-gunvor-nelson%CA%BCs-vision-of-editing/

Gunvor Nelson was an extremely influential teacher of mine. Between 1985 and 1995 I lived in San Francisco and was deeply inspired and supported by other artists and curators in the Bay Area experimental film community including Trinh T. Minh-ha, Karen Holmes, Steve Anker, Kathy Geritz, Jeanne Finley, Craig Baldwin, and George Kuchar. It was in San Francisco that I met Mark Street my soulmate and collaborator. In 2015, I traveled to Sweden with Mark to visit and shoot film with Guvnor Nelson in her home studio, two decades after she had left the Bay Area.

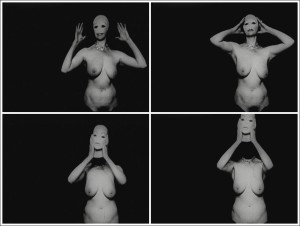

Gunvor Nelson is a moving image artist whose work makes you think about everything from the taste of a shiny green apple to the mortal coil. She was my teacher between 1987 and 1989 in the Master of Fine Arts program at the San Francisco Art Institute, a period in my life when I was first discovering the wonders of avant-garde film. Growing up in Memphis, Tennessee, I certainly did not have the kind of childhood where I was able to see experimental film in my local theater or even in the town museum. As a college student, I resisted film classes because the professors only seemed interested in the semiotics of Hollywood feature films. Not until I spent a year in Paris in 1981 did I discover that cinema could be a personal art like painting, poetry or photography. In fact, making movies allowed me to bring my love of all three of these mediums into one place of expression. It was also during this time that I first became aware that a person who wanted to make a film did not necessarily need to be a “director” of an entire cast and crew, but rather could have her hands on every element of the process. So, as you can see, I was ready to learn from a mentor who would share her own creative process with me, ultimately guiding me toward my own lifeʼs work as a filmmaker.

In 1985, I moved from the east to the west coast to begin graduate studies in the Film Department at the San Francisco Art Institute where I was able to work with some of the greatest filmmakers of the Avant-Garde: Ernie Gehr, Larry Jordan, George Kuchar, Carolee Schneemann and, of course Gunvor Nelson. Gunvor was the Chair of the department at that time. For two years, I sat with her for hours and hours in front of a 16mm editing machine watching my films in process (Note the word “process” not “progress”, as we never knew if the films were getting better, only that they were evolving). These long stretches of one-on-one time gave me the chance to learn from a brilliant, committed artist who had embraced all aspects of film production and post-production. From using a motion picture light meter and camera to working with the laboratory on the timing lights of a release print, Gunvor mastered every aspect of her art and was always willing to share this knowledge with her students. With this teacher-student relationship in mind, I have decided to travel back in time by revisiting Gunvorʼs famous editing treatise. In this way, I will try to look at my own 25-year career as a filmmaker through the lens of this ingenious guideline to editing. (You can view and download Guvnor’s original editing notes at the top of this page.)

“Before you shoot film, it is helpful to think through what style of editing would be most appropriate so that you will not leave out necessary liasons, steps and transitions.”

Gunvor encouraged her students to engage with their cameras as prescient editors who anticipated the needs of the film at all stages of production. Because we would have our hands on the trigger switch of the camera as well as the editing equipment, we had to think in both intellectual and physical ways about the movement and timing of a shot. Transitions were extremely important to Gunvor. She was always thinking about how to enter the front door of an image and how and when to get out. A shot was like an airport and the arrival and departure times of every single plane were critical, otherwise there might be too much chaos on the tarmac!

“Surprising solutions can be had with the most ʻdeficientʼ of material if you let it speak to you, if you learn what really is in the film …. Transitions help bridge potential disunity …. sharp jumps in the editing can be, at the right places, most exhilarating.”

One of the most lasting suggestions Gunvor made to me was that a filmmaker should always return to her outtakes just before she completes the edit of a film. Here, for example, you will find the moments when the film roll is just about to run out and beautiful fire-like orange flashes burst across the frame. I remember the time when my camera almost fell off the tripod during a shoot and so the film recorded what I originally saw as an ugly, embarrassing accident. According to Gunvor, these “mistakes” that were initially disregarded become extremely useful punctuation – like a period or an exclamation mark – that assists an editor in finding ways to complete a visual thought.

“A major aspect of editing involves finding the particular world of the film.”

To me, this statement implies that a good filmmaker edits from within the material and does not rely on a plot, narrative, script or rhetorical agenda. There is an organic integrity to the footage that guides the sculpting of the work.

“Repetition … is one method of building a memory within the film … of building its vocabulary.”

Because I identity so strongly with the precepts of experimental filmmaking, I have come to understand that the distinction between this kind of cinematic practice and that of a more conventional method of movie-making is the belief that each film must create its own specific idiom. A viewer of an experimental film will not speak this language prior to entering the theater but once the film is over, he or she will have been introduced to this unfamiliar mode of expression. As artists, we hope that our audience is both excited and happy about this experience and will come back for more “vocabulary lessons”. In this way, the spectator collaborates in the building of a cinematic memory that allows him or her to reference images found throughout the film. Like reading a poem, texture and rhythm are integral to all aspects of a visual and aural engagement.

Gunvor taught me to pay special attention to the energy that happens between two shots. Through the visualization and acceptance of this shift from one image to another, the spectator creates a particularly cinematic space that seems to exist within the cut itself. This is the reason why the viewing of an experimental film asks us to use our imaginations in order to create a surge or synapse of intellectual activity when we move temporally from one shot to the next. For a filmmaker like Gunvor, this change – whether it be a crash or a fluid shift – is nothing like the dialectic that Sergei Eisenstein wrote about in Film Sense, his famous materialist examination of film editing. Gunvorʼs interests are more aesthetic than political.

“The natural flow of the Western eye is left to right, which makes right to left motion have more

power.”

As most of us know, our readerʼs eye has been trained to move from the left side of the page to the right, over and over and over again. Thus, panning with a camera in the opposite direction feels absolutely unnatural. Even though we are not even talking about the act of reading, the repetitive gesture of that act has conditioned us to feel ill at ease with a movement that breaks this trajectory. For this reason, a right-to-left pan can appear very jarring, creating a fresh, surprising sense of unsettledness. Use this rupture from the norm to your advantage!

“Study … negative space.”

Like the French Post-Impressionist painter Paul Cézanne, Gunvor compelled her students to see the shapes that surround and transform objects. She wanted us to be aware of the way that the frameʼs aspect ratio interacted with the things that moved in and out of the image. Whether we were filming a human being performing a role, a beautiful glass bottle on a table, or a windmill on a hill, we had to be as aware of what was not there as we were of what was there. After working with Gunvor, I distinctly remember looking at a cloud formation in the sky one day. Most people search for animal shapes when they look up, but I could only stand in awe of the negative space.

“Pay attention to what kinds of colors are present … in what proportion do the colors exist and

play off of each other?”

I learned so much about color from Gunvor, too. She taught me to look at the world I had created in my images as a series of hues and intensities that could bounce against each other in the most stimulating of ways. Who cares about other content when you have color?

“How dark or light is the shot? Notice how sharp or soft an image is focused and also how the

contrast gives feeling to the photography.”

Eventually, while working with Gunvor, I realized that the editing schematic was often so important to her that it really did not matter what was actually on screen as long as I was able to construct a film with Nelson-approved visual integrity. Throughout the process, Gunvor taught me how to trace the shifts from dark to light and back to dark within and between shots so as to build a complex, unspoken, non-narrative cinematic universe. Sometimes we would disagree about an edit when I felt I had something specific to say or express and therefore needed to include a particular image that she believed did not meet her qualitative standards. These are the kinds of debates that are supposed to happen in an editing room.

“There are two divergent kinds of editing:

1) On one hand, where the cotton lays like padding around the structure – where one does not want to show the skeleton – to hide it – and not show how the film is made. The cut is as unnoticeable as possible.

2) On the other hand, where the cuts call attention to themselves and are featured, the structure is primary and forms the essential content.”

Experimental filmmaker Gregg Biermann was also a student of Gunvorʼs and remembers working with her:

“One thing that impressed me was showing her a rough cut of a film on a flatbed. She was critical of some of my editing; she thought it was sloppy. She didn’t say that I had to clean it up for the purpose of academic achievement but mentioned that she would never print a film that had those problems. There was a sequence toward the end of the film where I (unintentionally) flipped the optically printed image from right to left. Gunvor immediately zeroed in on this sequence of shots and interrogated me about it. Well, many years have passed since all of this but Gunvor might be happy to know that my work now is very, very precise.”

To understand Gunvorʼs theories of film editing, one must take the leap away from conventional narrative film where story is always at the forefront of a viewerʼs mind. Gunvor asked us to embrace the bumps, holes, and utter risks of the road – to relish in the form — rather than setting our sites on the more predictable pleasures of character and conflict. In this process, we can discover meaning within the frames of a formally adventurous experimental film.

After months or years of editing, the last step to making a 16mm film print requires the artist to communicate with a laboratory technician. Most filmmakers are completely baffled by the science of color and, therefore, have a difficult time articulating their desires in terms of the numerical changes in the cyan, magenta, yellow and black chromatic palette of each shot. Not so, Gunvor. She walked into the laboratory with a precise list of timing-light numbers.I remember hearing from several lab technicians that she understood the science of color printing better than any filmmaker they had ever met.

Gunvor concludes her guidelines to editing in this way:

“When you are really immersed, you, yourself, are totally interested in solving the ʻproblemʼ of the film, then you forget how much work you are giving to it, then the film emerges. Why did I not see it before?”

As Gunvor once explained to me, when you finish editing your beloved film, you will be ecstatic. Then the next morning you will feel a profound sense of loss. To be inside the editing of a film is an incredibly consuming fusion of the intellectual and the artistic. No matter what is going on in your home or in the world beyond, you have your film, and that, sometimes, is enough.

Note: This article was published in Sweden in the limited edition magazine OEI in Fall 2015, which is not online and is not available to readers outside of Sweden