Alexander Lenard: A Life in Letters

by Lynne Sachs

Published in The Hungarian Quarterly VOLUME LI * No. 199 * Autumn 2010

http://www.hungarianquarterly.com

For over seventy years, a steady stream of letters was exchanged between Alexander Lenard and members of my family in Memphis, Tennessee. Most of these reflections on everything from stock market prices to family trips, to the legacy of war to the cost of cranberry seeds, were exchanged between Sandor (he was called in the family by his Hungarian first name, without the accent) and my great-uncle William (a.k.a. Bill) Goodman. Luckily for me, my prescient uncle had a heart-felt, insightful appreciation for the epistolary vision he saw in his cousin Sandor’s missives. He kept every letter that he received from Lenard, as well as copies of his own correspondence.

In the mid-1980s, I became fascinated with Alexander Lenard’s story, wondering to what extent it could give me insight into our family’s heritage in Europe before and after the horrors of WWII. Aunt Hallie Goodman, Uncle Bill’s wife, and later Eleanor, their daughter, knew that I had chosen filmmaking as my life’s work. They appreciated my curiosity about and commitment to Sandor’s story and eventually offered me the entire archive to fathom what I could of this rich and troubling tale of hardship and survival. In 2009, I completed The Last Happy Day, an experimental documentary film inspired by the life of my distant cousin.

By interweaving excerpts from these letters into the visual and aural fabric of my film, I embrace the whimsy and the pathos that was Sandor Lenard. Always an exile, a victim of a kind of human “continental drift”, my cousin never felt “at home” in the synthesized post-war euro-culture he found in Brazil. Building a harpsichord on which to play Bach, reading thirteen languages and translating Winnie the Pooh into Latin allowed him to stay connected to an old-world life to which he would never return. The two decades I spent researching, traveling, shooting and editing my movie allowed me to explore the implicit paradoxes of a life both thwarted and nourished by the contradictions of a troubled time.

Interestingly enough, the Lenards were the only branch of our extended family that remained in Europe during World War II. In 2003, I travelled to Düsseldorf, Germany to meet Sandor’s son, Hansgerd Lenard, then in his late sixties. As I stood with my camera, he uncovered a trove of family diaries, letters and inscribed books from the 1920’s and 30’s. Inside each book, Sandor and his parents had meticulously transformed their obviously Jewish surname LEVY to a more Hungarian LENARD. Rather than destroying this direct reference to their hidden family identity, Sandor’s family, my sole remaining European relatives, meticulously erased. In their minds, the key to survival in early twentieth century Hungary would be pristine assimilation.

My own family, during that time, also refused to grasp fully the catastrophe that was Europe. With far less to lose, their methods of confronting imminent danger were similarly subtle. The earliest letters of our family correspondence begin around the turn of the century, but for our purposes, I will start with a letter between William’s father Abe offering help to Sandor’s father Eugene, a polyglot just like his son, in post-World-War I Hungary:

June 17, 1920, Dear Eugene: Our oldest son, William will graduate tomorrow at the University of Pennsylvania, the second is in military camp in Kentucky, the third is too small and is at home. Acting on your suggestion I am herewith enclosing you New York Exchange for $1,000.00 which from the figures that you gave me in your letter you can use to a very much better advantage in Budapest, than having this amount converted into Kronen in this country. I am sending this to you to use or invest, returnable in two or three years without interest.

Sincerely, Abe Goodman

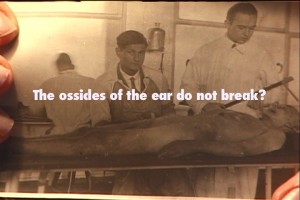

For the next 28 years, there did not appear to be a great deal of cross-Atlantic letter writing between the families, not until the end of World War II when William Goodman, now a successful Memphis attorney with four children, traveled with his wife Hallie to Rome where he made some remarkable discoveries about his cousin. During World War II, Sandor , a struggling doctor with Jewish lineage, had found refuge in Rome and had devised his own unique way to survive the traumatic world of occupied Italy. By 1948 he worked for the United States Army’s Graves Registration Service reconstructing the bodies of American soldiers killed in combat.

In a letter dated September 26, 1948, William and Hallie Goodman have just met Lenard for the first time. Together, they write to William’s mother Bobye Wolf who was directly related to the Lenard family through her mother Wilhelmina Levy, born in Worms, Germany in 1840. Here you will see Hallie refer to Lenard’s first son whom Lenard left in Germany with his German, Aryan, mother. She also refers to Lenarad’s second, Italian wife, Andrietta.

(Hallie) We went to Alexander’s home to see him, his wife and child. He’s a very intelligent man, but I am afraid not too practical. He doesn’t seem very anxious to come to the US even though they are destitute, and can barely manage to get along. Bill gave him a suit of clothes, and we took his wife Andrietta all our extra soap, a few pairs of hose, and a five-pound box of candy. Lenard says his son, Hansgerd, is almost starving in Germany and we promised to ask you to continue sending him boxes.

(William) Lenard was very easy to get along with –didn’t ask for a thing, which made me all the more anxious to try to help him. I arranged for the manager of Paramount in Italy to give him some translating work on subtitles.”

While making my films, I travelled to Sao Paolo, Brazil to film Sandor’s eighty-five-year-old wife, Andrietta. She described in vivid, almost dreamy, detail her husband’s macabre, medical work. I listened to her recounting his daily contact with the detritus of war, wondering to myself why we so rarely think about who is responsible for “cleaning up” the dead. In The Last Happy Day her graphic, realistic recollections stir visual ruminations on her husband’s futile act of posthumous, cosmetic surgery.

By the early 1950s, Sandor reaches out to William with a kind of forlorn intimacy one might not expect between two men who have only met once in their lives

March 25, 1950. Dear Cousin Bill, My conscience is the worst: I have still not completed the research (on our family), which is after all even more interesting for myself than for you… The fact is that after four years as a civil employee of the US Army I had to build a new base for my existence in medical writing. I wrote and published a book on children’s diseases and started one on painless childbirth. ….It’s the depressing present that renders looking into the past such a sorrowful undertaking. One hoped during the war that there would be a better world. It is hard to realize that the victims died so uselessly. Race hatred not only survived, but also came out stronger than ever. Europe and the world found a new and holy pretext for hate. I really hope that I am mistaken when I think the United States is becoming a dangerous place to live.

As Sandor’s world fell into a wartime state of hunger and decay, he delighted in the absurd and the arcane. His love of literature and language was his life raft, his potent means of resistance. Speaking, reading and writing Latin kept him from what Natalie Ginzburg, another writer trapped in occupied Italy, called “the fury of the waters and the corrosion of (our) time.”

Soon afterward, Sandor left for South America, never to return to the Europe that had so fed his imagination and his mind. In my film, I contrast the haunting confinement and violence Sandor experienced in Rome during the Nazi occupation with the verdant emptiness of his later life in remotest Brazil. I juxtapose Sandor’s fearless introspection in his unpublished letters with my imagined visualization of his idyllic life in his house in the woods. The geography of his NOW simultaneously saddens and protects him from the threats he fears are still percolating on the other side of the Atlantic.

Correspondence with my family does not resume again until a decade later in 1961, when Lenard publishes Winnie Ille Pu, his Latin translation of Winnie the Pooh, and enjoys surprising worldwide success. Goodman gets word of the publication and brazenly takes things into his own hands by writing this Feb. 6, 1961 letter to the Editor of Time Magazine in the Time and Life Building in New York City. Clearly, Goodman sees the story of his cousin as an intriguing mix of quixotic impulses and stubborn intellectualism.

In the spring of 1961, the two cousins finally make contact once again. Sandor writes a letter to Memphis, explaining his disappearance and his unexpected literary glory. Clearly, Lenard does not yet know that Goodman is not only well aware of his cousin’s publication but may also be responsible for the press coverage.

Dear Cousin William, ….On the long way from Rome into the forest of Santa Catarina, Brazil I had lost your home address and I had abandoned all hope of tracing you again. Now, by the strangest chance of the world, I have become a best-selling author – or at least translator. Thanks to Winnie Ille Pu. LIFE magazine has published an article about my life and work. A reporter visited me and sent notes to the USA. They wrote the piece as an editorial, a success story and the result is a hopeless mess of misunderstandings, half-truths and outright inventions. On the other hand, more than 100 papers have published reviews about my Bear – which seems on the way to relieve American children of the menace of irregular verbs and defective nouns. For the first time since 1938, I dream about a settled life. At present, this is only a dream, because even after the publication of 84,000 copies in the USA, I have not received a contract for the book, let alone a cent. Please let me know how you are getting on! I remember you had twins. They must be beyond Winnie the Pooh age by now! With love, your Sandor

Thrilled by his rejuvenated contact with his Hungarian distant cousin relocated to the forests of Brazil, my Uncle Bill responds immediately and practically to Sandor’s concerns about money. In addition, he describes his travels to Berlin, Moscow, Leningrad, Helsinki, Amsterdam, London and Paris with the family, giving Sandor a window into a wealthy American’s “if it’s Tuesday, it must be Moscow” itinerary.

Dear Sandor, It was shocking to learn that your royalty situation has not yet been straightened out. If I could be of the slightest assistance in working out your difficulties with the publisher, please let me hear from you. Sincerely yours, William

Months later, this letter arrives from Brazil on May 26, 1961, politely spelt in American English by Lenard:

Dear William, Traveling is wonderful if you do it in a voluntary basis. After having been shoved around half the globe, I got allergic to the outdoors. I think a travel agent would have an easier time selling a round trip of the Mediterranean to Odysseus himself than to me. The less I move from my hideout 80 miles inland from Blumenau (the nearest village) in the greenest most peaceful valley in the world, the more I enjoy letters which have traveled a long way. Winnie Ille Pu has brought me in contact with Latinists the world over. I certainly never thought my Bear would reach the best-seller list, where he now enjoys his life for the 12th week running. I still have not received a cent from my publisher. Should I really receive royalties some day, I am going to become a sort of millionaire – or at least return to the middle class our family left in 1938. In 23 years of existence as a “have-not”, I am ready to accept it for the rest of my life.

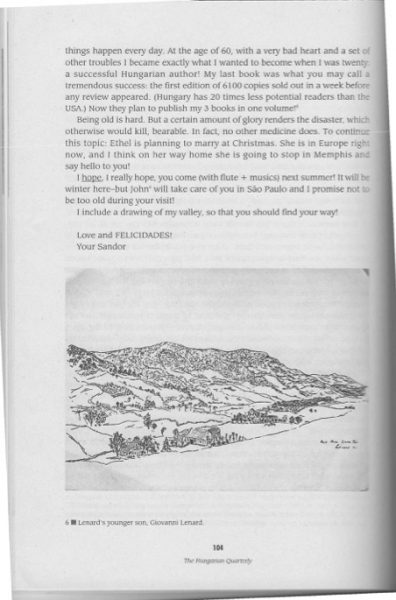

I have a wooden house, half way between cabin and castle, with such incredible objects as a bathroom and a piano (next bathroom: 20 miles away – next piano: 80 miles). The satellite I see flying occasionally across the evening sky is the only sign of the present. I am sure that you would enjoy the silence and the distance from worldly events. Translating modern books into Latin is not quite paradoxical here. Won’t you come and see for yourself? Your Sandor”

Because William is an attorney and is able to arrange the legal matters pertaining to Sandor’s royalties for his book, his next letter dated June 7, 1961 arrives with exactly the news Sandor wants to hear.

Dear Sandor, Your publisher confirms that you will receive the full 5% royalty and there will be no further arguments. Your valley certainly sounds attractive. As I get harassed by all the hour-to-hour difficulties of so-called civilization, your mode of living really becomes more inviting. Sincerely yours, William

Sandor’s subsequent July 12, 1961 letter, which is included here in its entirety, is a profound meditation on civilization and the ways Sandor has come to understand and perhaps reject it. In the letter he speaks about the joy of living amongst the flora, and his love of cranberries in particular. I remember hearing my Aunt Hallie’s stories about putting packages of these seeds inside a roll of newspaper and sending it off to our distant cousin in the southern hemisphere. How charming and eccentric we all thought this was, at the time, not yet having a sense of our distant cousin’s longings.

The early 1960s mark a time in the cousins’ correspondence in which letters seem to flow almost monthly. Sandor finally receives a check for $8000 and claims that he could now be the richest man in the valley, except for the fact that he cannot cash the check.

Dear William, I thank you very much for the seeds and have sown them with care. I also enjoyed the papers the seeds were wrapped in! It is nice to hear sometimes about the outside world. I love Brazil for all the space and freedom it gives and the more I hear about neutrons and rockets the more I love it, but you can’t ask for the advantages of uncivilization without some drawback. Absolute freedom and good bathrooms, space and chamber music are contradictions. I chose freedom and renounced the pleasures of a country where you pay with checks. Still, let me say to you again how happy I feel knowing that you represent my interests up there (in the U.S.). The bonds between our families outlasted the centuries and are still strong. Gratefully and with good wishes, Sandor

By 1962, life is good for Sandor, his wife and his second son Giovanni.

Dear William, The money arrived safely. Andrietta is refurnishing the house and I am buying a forest. I am busy writing an anti-fascist Roman cookbook, publishing a Latin translation of Francoise Sagan’s Bonjour Tristesse, and writing a novel in a secret almost dead language called Hungarian. So you see, I am happily planning for 1963, as if my coronaries would be fit for long term projects and the world were waiting for humanistic and gastronomical literature. As to the heart, I trust that big doses of silence will have some dilating effects upon the arteries. Very much cannot be achieved by medical means. The fact is that bullets that do not actually touch the body also hurt. The only medicine against world events is distance, safe distance. We are busily typing a list of more seeds we could like, so my ‘castle’ will be surrounded by flowers. My Bach cantatas have already changed the atmosphere of wilderness into something else. Your old Sandor

Sandor comes to live with my Uncle William’s family in Memphis for a few months in 1968, a time of palpable racial tension, street protests and nightly curfew, the same year Martin Luther King was assassinated in a small motel in our downtown. Upon his return to his cabin in Santa Catarina, he begins a correspondence with my cousin Eleanor, Uncle William’s daughter, then a senior in high school. His November 27, 1969 letter to Eleanor (here in its entirety) is an eloquent homage to youth, wonder and discovery.

In 1970, Sandor sends his own teenage son Giovanni to live for a few months with their American relatives in Memphis. Giovanni returns to Brazil relating that William’s own adult children have each begun families in homes near that of their parents.

Dear William, My son tells me that you are all living near to one another. Almost all of my life was a series of headaches and the rest was longing and homesickness. My headaches have passed but longing and homesickness are here more than ever and I envy those who can say ‘We are all at home.’ Abrasos, Sandor

To Eleanor, he writes another letter, offering a frank description of his own health.

Dear Eleanor, I am a very bad letter writer now. Though my right eye is far from good, I must finish the translation of my most recent Hungarian book into German. Despairing to get a new heart I’ll certainly try to make the old one function, with all its burdens. As soon as you realize you have a heart, there is something wrong with it. Take care, do not ever realize it! Sandor

On September 25, 1970, Sandor’s own doctor writes a personal letter to the family, stating that for the past few months Sandor’s working capacity has declined, and that he has lost his drive to write, study or read.

Soon afterward, he writes his own obituary and dies.

Lynne Sachs (www.lynnesachs.com)

is a filmmaker making experimental documentary films since the mid-1980s. In the The Last Happy Day she constructed a narrative triangle between Lenard, her Uncle William and herself. While their presence in the film is grounded in a dialogue from the past, her participation is more temporally and geographically fluid, creating an evolving relationship of distance and intimacy through voice and text. The film (available from the New York Film-makers Cooperative at www.film-makerscoop.com) premiered at the New York Film Festival and was shown by Duna Television on March 16, 2010, the 100th anniversary of Lenard’s birth.