Short Redhead Reel Reviews for the week of June 24

Sun This Week

By Wendy Schadewald

June 23, 2022

https://www.hometownsource.com/sun_thisweek/free/short-redhead-reel-reviews-for-the-week-of-june-24/article_bad78618-f32e-11ec-a1f2-37945ed3047d.html

Rating system: (4=Don’t miss, 3=Good, 2=Worth a look, 1=Forget it)

www.shortredheadreelreviews.com

For more reviews, click here.

“The Black Phone” (R) (3) [Violence, bloody images,a some drug use, and language.] [Opens June 24 in theaters.] — When a smart, bullied, doggedly determined, 13-year-old baseball pitcher (Mason Thames), who lives with an abusive, alcoholic. widowed father (Jeremy Davies) and his feisty, psychic sister (Madeleine McGraw), who sees visions in her dreams, is kidnapped by a devil-mask-wearing killer (Ethan Hawke) known as the Grabber and held in a soundproof basement in North Denver in 1978 in Scott Derrickson’s taut, original, tension-filled, well-acted, suspenseful, twisting, 102-minute, 2021 thriller based on Joe Hill’s 2004 short story, he quickly starts to receive calls from a disconnected black phone the killer’s previous victims (Tristan Pravong, Miguel Cazarez Mora, Jacob “Gaven” Wilde, Jordan Isaiah White, and Brady Hepner) who give him advice and tips on escaping while detectives (E. Roger Mitchell and Robert Fortunato) search for the missing Colorado students.

“Cured” (NR) (3.5) [Played June 17 as part of AARP’s Movies for Grownups and available on Amazon Prime Video and various VOD platforms.] — Patrick Sammon and Bennett Singer’s gripping, award-winning, eye-opening, educational, powerful, candid, insightful, 80-minute, 2020 documentary that examines homosexuality as a mental illness, the use of various treatments to cure the condition, and the American Psychiatric Association’s decision in 1973 to remove it as a mental disorder in the “Diagnostic and Statistical Manual” and consists of archival photographs, film clips, and interview snippets with minister and activist Dr. Magora Kennedy, APA Nomenclature Committee member Robert Campbell, psychiatrists (such as Dr. Lawrence Hartmann, Dr. Richard Pillard, Dr. Richard Green, Dr. Charles Socarides [archival footage], Dr. Irving Bieber, Dr. Judd Marmor [archival footage], and Dr. Jerry Lewis [archival footage]), APA CEO and medical director Dr. Saul Levin, psychologist Dr. Evelyn Hooker (archival footage), electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) patients Rick Stokes and Sally Duplaix, photographer and activist Kay Lahusen, writer and activist Gary Alinder, activists Don Kilhefner and Barbara Gittings (voiceover and archival footage), astronomer and activist Dr. Frank Kameny (voiceover and archival footage), journalist and activist Ronald Gold, Dr. Charles Socarides’ son Richard Socarides, Dr. John Fryer’s friend Harry Adamson, Dr. John Fryer (voiceover and archival footage), and psychologist, activist, and former schoolteacher Charles Silverstein.

“Elvis” (PG-13) (3.5) [Suggestive material, smoking, substance abuse, and strong language.] [Opens June 24 in theaters.] — Superb acting, costumes, and makeup dominate Baz Luhrmann’s entertaining, factually inspired, captivating, over-the-top, well-written, star-studded (David Wenham, Kodi Smit-McPhee, Anthony LaPaglia, Xavier Samuel, Luke Bracey, Kate Mulvany, and Nicholas Bell), 159-minute biographical film in which legendary, talented, charismatic, gyrating, rock’n’roll singer Elvis Presley grows up as an inquisitive boy (Chaydon Jay) in a Black neighborhood in Tupelo, Miss., with his alcoholic mother (Helen Thomson) and felon father (Richard Roxburgh); Black influences on his music and his rise to fame orchestrated by his dysfunctional relationship as an outspoken singer (Austin Butler) with Carnival-educated, gambling-addicted, duplicitous manager Colonel Tom Parker (Tom Hanks) who cheated him financially for more than 20 years; and his marriage to Priscilla Presley (Olivia DeJonge) who he met overseas while in the Army.

“Escape the Field” (R) (2) [Violence and language.] [Available June 21 on DVD and Blue-Ray.] — After six frightened strangers (Shane West, Jordan Claire Robbins, Theo Rossi, Tahirah Sharif, Elena Juatco, and Julian Feder) suddenly regain consciousness in a remote, perpetual, trap-filled cornfield, which is guarded by a creepy scarecrow, with sirens blaring and left with only a single-bullet gun, a container of matches, a lantern, a knife, a compass, and a flask of water in Emerson Moore’s convoluted, tension-filled, violent, 88-minute psychological thriller with overly dark visuals, they struggle to work together to find a way out while being stalked by a menacing, mysterious creature (Dillon Jagersky) at every turn.

“Fast Five” (R) (3) [Intense sequences of violence and action, sexual content, and language.] [DVD and VOD only] — While a hulking, tenacious, special FBI agent (Dwayne Johnson) and his task force team up with a rookie Brazilian cop (Elsa Pataky) to track down an escaped convict in Brazil after three agents are murdered during a three-car heist from a moving train in this frenetic-paced, action-filled, entertaining film packed with car crashes and stunning choreography, three felon professional drivers (Vin Diesel, Paul Walker, and Jordana Brewster) and their cohorts (Tyrese Gibson, Ludacris, Matt Schulze, Sung Kang, Gal-Gadot, et al.) plan an elaborate, dangerous $100 million robbery from a ruthless drug dealer (Joaquim de Almeida) and his henchmen (Michael Irby, et al.) in Rio de Janeiro.

“Jumping the Broom” (PG-13) (2.5) [Some sexual content.] [DVD and VOD only]— Tensions escalate, tempers flare, secrets are revealed, and nuptials are threatened in this engaging, predictable, romantic, star-studded (Julie Brown, T.D. Jakes, Gary Dourdan, Pooch Hall, et al.) click-flick drama when a widowed, feisty postal worker (Loretta Devine) with anger management issues leaves Brooklyn with her best friend (Tasha Smith), her flirty brother-in-law (Mike Epps), and the best man (DeRay Davis) to meet the beautiful fiancée (Paula Patton) her handsome, successful son (Laz Alonso) is about to marry, along with the bride’s wealthy parents (Angela Bassett and Brian Stokes Mitchell) and other wedding guests (Meagan Good, Valarie Pettiford, Romeo, et al.) during a weekend of celebratory festivities before the wedding on Martha’s Vineyard.

“Paid in Blood” (R) (3) [Subtitled] [Available June 26 on various digital platforms.] — Bodies drop like flies in Yoon Youngbin’s gripping, action-packed, fast-paced, dark, blood-soaked, violent, 118-minute, 2021 noir crime thriller with awesome fight choreography in which a ruthless, ambitious, power-hungry, former South Korean assassin (Jang Hyuk) from Seoul pits rival gangs against each other when he decides to challenge powerful, knife-wielding members (Yoo Oh Sung, Oh Dae Hwan, et al.) of a crime ring in 2017 after he learns that they are building the largest casino in Asia in Gangneung, and the crime lord (Kim Se Joon) then puts a target on his back while a Korean lieutenant detective (Park Sung Keun) tries to protect his gangster friend and to control the escalating mayhem and murders.

“Potato Dreams of America” (NR) (3) [Available June 21 on Blu-ray™.] — Wes Hurley’s weird, factually based, award-winning, coming-of-age, arty, twist-filled, wit-dotted, unpredictable, 95-minute, 2021 autobiographical comedy in which a struggling, wannabe-actor, movie-loving, gay student (Hersh Powers/Carter Coonrod) grows up in the USSR in the 1980s with his compassionate, open-minded, prison doctor/actress mother (Sera Barbieri) and ends up as a teenager (Tyler Bocock) moving with her to Seattle to the disappointment of his father (Michael Place) and grandmother (Lauren Tewes) when she becomes a mail-order bride (Marya Sea Kaminski) to a duplicitous, conservative American (Dan Lauria) and finds happiness with various lovers (Nick Sage Palmieri, Cameron Lee Price, Aaron Jin, Bailey Thiel, Dexter Morgenstern, Drew Highlands, Dylan Smith, and Randy Phillips) after he comes out of the closet and is free to be himself.

“Swedish Auto” (NR) (3) [DVD and VOD only]— A touching, sad, 2006 film in which a shy, music-loving mechanic (Lukas Haas), who works with the kindhearted owner (Lee Weaver) and an African-American mechanic (Christ Williams) at a small-town garage in California, pines for an out-of-reach violinist (Brianne Davis) while getting closer to a beautiful waitress (January Jones) who lives with her mother (Anne Brown) and her abusive, cancer-stricken boyfriend (Tim De Zarn).

“There Be Dragons” (PG-13) (3) [Violence and combat sequences, some language, and thematic elements.] [DVD and VOD only]— While a journalist (Dougray Scott) travels to Madrid to gather information for a historical epic set against the violent backdrop of the Spanish Civil War in 1918 about the life of St. Josemaría Escrivá de Balaguer (Charlie Fox), who founded the Roman Catholic Opus Dei and was later canonized by Pope John Paul II in 2002, in this poignant, compelling, factually inspired, colorful, 2-hour film highlighted by striking cinematography, he is shocked to learn that his own terminally-ill, estranged father (Wes Bentley) was a childhood friend of the priest who sought peace through the beauty of everyday life, but they became bitter enemies when he fought as a soldier in war-torn Spain and ended up being driven by his jealous anger after becoming smitten with and rejected by a gorgeous Hungarian (Olga Kurylenko) who falls for another Spaniard (Rodrigo Santoro).

“This Prison Where I Live” (NR) (3) [DVD and VOD only] — Veteran documentarian filmmaker Rex Bloomstein narrates his eye-opening, informative, poignant 2010 documentary about popular, feisty, courageous, outspoken standup Burmese comedian, film star, poet, and playwright Zarganar (aka Maung Thura) from Yangon, Burma, who was sentenced by the oppressive military junta in Sept. 2007 to serve 3 weeks in prison for his support of the monks during the Saffron Revolution and again in 2008 to serve 59 years (reduced to 35 years) for his continual satire of the tyrannical government, censorship, life in Burma, and speaking to the press about the government’s shortcomings after Hurricane Nargis; famous standup German comedian Michael Mittermeier joins the filmmaker in a return to Burma to gain further insight to Zarganar’s current plight and to showcase Myitkyina Prison in which he now resides.

“Twisted Roots” (NR) (3) [Subtitled] [DVD and VOD only] — While a suicidal, terminally-ill, Finnish antiques store owner (Pertti Sveholm), who has a free-spirited 16-year-old daughter (Emma Louhivuori) and an imaginative, adopted daughter (Silva Robbins) from China, tries to tell his biological children about his inherited, debilitating, degenerative disease and to reconnect with his estranged adult son (Niko Saarela) and young grandson (Leo Leppäaho) in this gut-wrenching, down-to-earth, 2009 film, his distraught, financially strapped wife (Milka Ahlroth) tries to figure out to raise $150,000 Euros due to the reckless spending of her brother (Jarkko Pajunen) without burdening her husband.

The following films play June 23-30 at BAMcinemaFest 2022 at BAM Rose Cinemas; for more information, log on to https://www.bam.org/programs/2022/bamcinemafest:

“Actual People” (NR) (2.5) — Kit Zauhar’s realistic, down-to-earth, low-budget, predictable, 84-minute, 2021 film in which an apathetic, emotionally distraught, anxious, constantly complaining, philosophy major, biracial Asian-American college student (Kit Zauhar), who was dumped by her boyfriend (Randall Palmer) of three years in New York City and then asked by her roommate (Henry Fulton Winship) to move out, wastes time partying and hanging out in bars, engaging in one-night stands, and pursuing an Asian man (Scott Albrecht) from her hometown of Philadelphia rather than trying to keep focused to finish her coursework in order to graduate and make plans for the future and not causing her concerned parents (Shirley Huang and Richard Lyntton) more worry.

“Alma’s Rainbow” (NR) (3) — When her eccentric, wild, free-spirited lounge singing aunt (Mizan Kirby) unexpectedly shows up after spending 10 years performing in Paris in Ayoka Chenzira’s engaging, multifaceted, well-acted, coming-of-age, humorous, 90-minute, 1993 film highlighted by terrific costumes, a feisty, rebellious, Brooklyn student (Victoria Gabrielle Platt), who gets into trouble with the nuns at the Catholic school, entering puberty gets help and advice from her estranged aunt in her relationship struggles with her strict, conservative, straitlaced salon owner mother (Kim Weston-Moran) and about a boy (Lee Dobson) she likes.

“The Body Is a House of Familiar Rooms” (NR) (3.5) — Stunning imagery dominates Eloise Sherrid and Lauryn Welch’s compelling, colorful, creative, imaginative, artistic, informative, 10-minute, 2021 documentary that intertwines gorgeous artwork by painter Lauryn Welch, live-action footage, and commentary by Eloise Sherrid and girlfriend Lauryn to try describe the day-to-day life of Samuel Geiger who has Ehlers-Danlos Syndrome, which affects connective tissue and nerves in the body that “vibrates with pain” and the smoking of marijuana that partially relieves his symptoms and improves mobility and functionality.

“Chee$e” (NR) (3) [Subtitled] — After an ambitious, perpetually broke apprentice cheesemaker (Akil Williams) learns his craft from a kindhearted master cheesemaker (Piero Guerini) in Trinidad and Tobago and then discovers that his girlfriend (Yidah Leonard), who is the daughter of a religious restaurant owner (Binta Ford), is pregnant in Damian Marcano’s quirky, award-winning, well-acted, humor-dotted, 105-minute film highlighted by wonderful cinematography, he must abandon his dream of leaving the island and concocts a plan to work with the local drug dealer (Trevison Pantin) to earn money by selling marijuana with his friend (Julio Prince) by hiding it in blocks of cheese while becoming suspicious targets of a tenacious police sergeant (Kevin Ash).

“Crows Are White” (NR) (3) — Amazing cinematography and landscapes highlight Ahsen Nadeem’s captivating, poignant, touching, thought-provoking, educational, 97-minute documentary in which L.A.-based filmmaker goes to mist-enveloped monastery atop Mt. Hiei near Kyoto, Japan, to gain insight, answers, and direction from Tendai “marathon” monks, including head Buddhist monk Kamahori, who put their bodies and minds through unimaginable, tortuous suffering and pain, such as the Kaihōgyō ritual where monks walk 1,000 days without food or sleep, to reach Nirvana, regarding his personal struggles with life and religion and his dishonesty and conflict with his estranged devout-Muslim Pakistani parents who live in Ireland and are unaware of his 3-year marriage to his patient, non-Muslim wife (Dawn Light Blackman) and gains a meaningful friendship with wannabe-sheep-farming, heavy-metal-loving, dessert-obsessed, calligraphy-writing, unorthodox, apprentice monk Ryushin when his is expelled from the 1,200-year-old monastery.

“The Feeling of Being Close to You” (NR) (3) [Partially subtitled] — Ash Goh Hua’s engaging, heartbreaking, realistic, poignant, heartwarming, 12-minute autobiographical film in which the Singapore filmmaker examines the longtime dysfunction in her family while growing up with her abusive mother she was unable to hug and now tries to connect both physically and emotionally through the use of intimate conversations, phone calls, and videotapes with her distant mother that she was unable to do as a young girl.

“Ferny & Luca” (NR) (1) — The plot takes a backseat in Andrew Infante’s bizarre, slow-paced, award-winning, avant-garde, redundant, low-budget, 70-minute, 2021 film in which a handsome, unemployed, money-strapped Brooklynite (Leonidas Ocampo) falls for a free-spirited, ambitious, wannabe singer DJ (Lauren Kelisha Muller), who commiserates about her troubles with a close friend (Alexa Harrington), but their tumultuous relationship seems to go nowhere.

“Happer’s Comet” (NR) (1) — Nothing happens in Tyler Taormina’s experimental, nonsensical, dialogue-free, oddball, surreal, dark, 62-minute film that follows an eclectic group of people, including a woman (Gianina Galatro) meeting a lover (Jax Terry) in a cornfield, a dog-walking insomniac (Dan Carolan), an old woman (Grace Berlino) resting at her kitchen table, a driver (Michael Guglielmo) falling asleep at the wheel, a rollerskater (Tim Sullivan) going around the neighborhood, and a rollerblader (Tyler Taormina) traversing the sidewalks, in the middle of the night on Long Island.

“Last Days of August” (NR) (2) — Rodrigo Ojeda-Beck and Robert Machoian’s morose, award-winning, depressing, arty, unexpected, 13-minute documentary that showcases dilapidated stores and broken down vehicles to emphasize the death of small towns in Nebraska as residents discuss their frustration, anger, and helplessness from experiencing the pain of life passing them by and the realization that they are powerless to combat the many things that are making life miserable, which causes some people to turn to religion, crackpot theories, and blaming others, and how big box stores such as Walmart and Costco, the advent of the Internet, and the rise of Amazon have put a dagger in the heart of small towns.

“ᎤᏕᏲᏅ (Udeyonv) (What They’ve Been Taught)” (NR) (3.5) — Awesome scenery and cinematography dominate Brit Hensel’s intriguing, heartwarming, inspirational, educational, 9-minute documentary, which was filmed on the Qualla Boundary in North Carolina and in the Cherokee Nation in Oklahoma, that examines through storyteller Thomas Belt how the Cherokee people try to be responsible as they live in this world so that it’s a give and take with nature.

“Portal” (NR) (3.5) — Rodney Evans’ captivating, poetic, down-to-earth, poignant, candid, 12-minute documentary that follows single filmmaker Rodney Evans who used striking poetry to stay connected with the outside world and his friend Homay King used other communication venues while she struggled with loneliness and isolation as she recovered from unconfirmed COVID-19 during the pandemic in 2020.

“Shut Up and Paint” (NR) (3) — Titus Kaphar and Alex Mallis’ engaging, award-winning, original, inspirational, 20-minute documentary that showcases the historically relevant paintings of talented African-American artist Titus Kaphar and the futile efforts of art critics to stop the activist who is involved in promoting racial justice and equality from speaking out through his artwork and includes commentary by Yale philosophy professor Jason Stanley.

“Sirens” (NR) (2.5) — Heavy trash metal music highlights Rita Baghdadi’s award-winning, insightful, inspirational, behind-the-scenes, 78-minute vérité style documentary that follows the friendship and struggles of twentysomething songwriters and guitarists Lilas Mayassi, who has a Syrian girlfriend Alaa, and Shery Bechara who cofounded the five-member (guitarist Lilas Mayassi, guitarist Shery Bechara, vocalist Maya Khairallah, bassist Alma Doumani, and drummer Tatyana Boughaba), heavy thrash metal Lebanese band Slave to Sirens in Beirut, Lebanon, amidst political turmoil, explosions, homophobia, ongoing anti-government protests, and culture constraints.

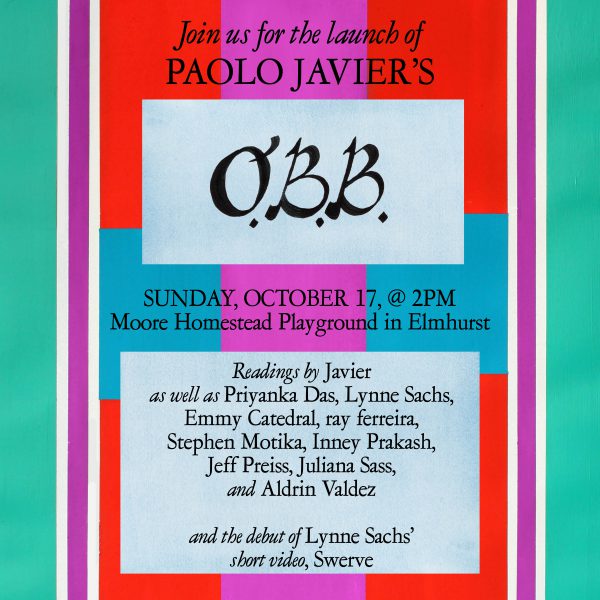

“Swerve” (NR) (3) [Subtitled] — Lynne Sachs’ intriguing, original, arty, well-written, 8-minute film in which performers Emmy Catedral, Ray Ferreira, Inney Prakash, Jeff Preiss, and Juliana Sass recite Paolo Javier’s Original Brown Boy poems from “Nightboat Books” as they wander around a food market and playground in Queens, New York.

“When It’s Good, It’s Good” (NR) (2.5) — Alejandra Vasquez’s educational, disheartening, gritty, down-to-earth, 16-minute documentary in which the filmmaker goes home to Denver City, Texas, to document the ups and downs of the fluctuating oil business and its devastating effect on the West Texas town’s population through interview clips with locals, including district attorney Bill Helwig, truck driver Arturo, teenager Dezy, and housewife Claudia.

“Winn” (NR) (3.5) — Joseph East and Erica Tanamachi’s gripping, educational, surprising, 17-minute documentary that chronicles the valiant efforts of Georgia activist and RestoreHER founder Pamela Winn, who was formerly incarcerated and pregnant, to pass in 2019 the HB345 Dignity Bill to legally stop the solitary confinement and shackling of imprisoned pregnant convicts in Georgia and in 2018 the First Step Act prohibiting shackling of pregnant women on the federal level.

Wendy Schadewald is a Burnsville resident.