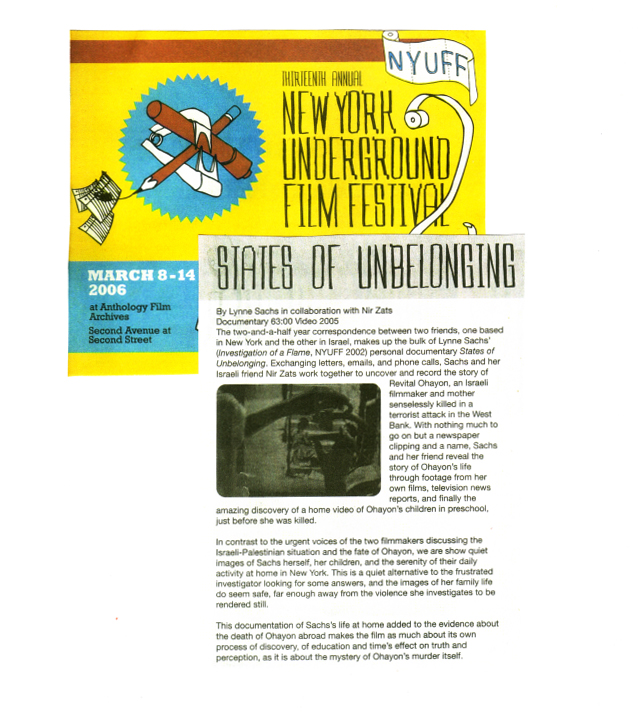

STATES OF UNBELONGING a film by LYNNE SACHS

in collaboration with NIR ZATS

63 minutes

Hebrew spoken by children

“When I am big and someone dies, I am going to go to the funeral.”

“You can put a doll on the grave, just like in the story.’

Dear Lynne,

I patiently wait for the sand to sink, for the water to get clear.

Israel is a very small place and in a way very isolated. Being surrounded by

hostility is definitely getting to me. The hostility of war and terror and the hostility of people’s aggressiveness toward each other. So much hatred.

It is hard for me to become involved as an activist. For now catching up with the headlines over coffee in the morning is enough.

Every now and then I consider coming back to New York, being a student again, carrying a camera.

Hope you are well,

Nir

Dear Nir,

Do you ever have the feeling that the history you are experiencing has no shape?

Even as a teenager I was obsessed with history’s shifts and ruptures. Wars helped us order time. A war established beginnings and endings. There is “before”. There is “during”. There is “after”.

Lynne

PHONE CONVERSATION

LYNNE: Hey, Nir, did I wake you up?

NIR: No, I’m fine.

LYNNE: I just wanted to tell you about this article I read today in the Times that upset me so much. It was about a woman who reminded me of myself. Her name was Revital Ohayon. She was a filmmaker, a teacher, a mother. She was killed on a Kibbutz, Kibbutz Metzer. What do you know about it?

NIR: Oh, yes, it was horrible. Have you heard the details of the story, what happened, that terrorists got into her home when she was at home at night with her two kids and actually shot them. I will think about it and right you more things.

LYNNE: Alright, bye for now.

NIR: Bye, bye.

_________________________________

On my map, Metzer is not far from Jenin, only a thumb’s distance from the kibbutz. Isn’t Jenin a Palestinian refugee camp, the site of killings? All I know is its destruction.

November 15, 2002

How are you Lynne?

Living in Israel is closely related to Buddhist thinking. The encounter with death is so immediate in Israel. You have to be prepared for your own death. As grim as it sounds, it’s just statistics.

Thoughts about death cross people’s minds on a minute to minute basis. Imagine the terror and fear in people’s minds on the other side of the Green Line, on the other side of the Wall.

Yes, I know about Revital. Everyone is talking about it. Did you know her husband heard the gun shots over the phone?

Yours, Nir

Dear Nir,

I’ve made so many phone calls to Kibbutz Metzer. Today I finally reached an elderly secretary. “Yes”, she told me, “this is the Kibbutz where Revital Ohayon lived and was killed.” The woman didn’t seem to know more than that.

I wonder what they make at the Kibbutz factory – jars of pickles, buttons, machine parts?

PHONE CONVERSATION

NIR: Hello Lynne, did I tell you that I saw Revital’s husband, it was on the news, on the weekend broadcast, and they interviewed him about what he was going through, and since you were interested in her I was trying to think about what he’s actually going through….

I have the number for her former husband, Avi Ohayon, the man who heard it all from his phone, as the killing happened.

PHONE CONVERSATION cont

NIR: ….for me usually it’s very alienated, you read the news, you see what happened, but you’re not going to the families of the casualties and asking how they feel, or putting yourself in their situation….

Dear Lynne

Did you know that this week is the Jerusalem Film Festival?

Parallel to it is the Ramallah International Film Festival. Ramallah is a big city on the Palestinian side of the border. I wish I could visit to show my films and also to see film in a theater over there. I would have a drink in the local Palestinian café. See a life that is so close to me and yet so far away. Separated and strange.

It exists as the Palestinian town from the news. I can only imagine, of course, since I have never visited myself. It is quite impossible for me as an Israeli to experience Ramallah.

Ramallah Dreaming.

Soon,Nir

�August 18, 2003

Dear Nir,

I need you to somehow get your hands on her movies, and also to photograph the land for me, as Revital would have experienced it – the kibbutz, Haifa where she grew up, the Northern coast, Tel Chai where she went to film school.

I am not asking you as a teacher, but as a friend. Did you know that I have never been to Israel? I missed those few moments of peace.

Lynne

�August 20, 2003

Lynne,

It sounds so sad when I read your words, “I missed the few years of peace.” Like missing an old relative that passed away and will never return. I was drafting a message to you when your mail arrived. How can I describe my feelings? It’s all not so clear. I remember the opening sentence from Burroughs’ Naked Lunch, “I can feel the heat closing in.”

Nir

Write soon, tell me what you can do, And, no, this isn’t another assignment, just a request from a friend. Really.

Lynne

By now I think I must have called at least fifty times, only to hear a series of Hebrew numbers recited to me, like a wall of digits forbidding my entrance. If Avi is not reachable, I tell myself that he wants nothing to do with the me, that he has withered with sadness, or that his phone has merely been turned off.

August 25, 2003

Nir,

I called Avi in Tel Aviv again this morning. He is so kind, almost at ease, willing to talk. Yes, he told me, she was just about to finish a film about the “generation gap.” There are so many gaps between us, she was only trying to fill one, with her filmmaking.

I’ve been waiting for eight months to see her movies. Will you go to his home, ask him for the tapes, talk to him, and yes, take your camera? Tell me what happens,

Lynne

Lynne,

I was walking by myself in Metzer this morning.

For a minute, I thought about the terrorist coming towards me.

I protected myself by holding the Super 8 camera in its pistol grip. Transformed

it into an Uzi machinegun.

Then, I came back to my senses, saw an old woman hoeing her garden. Behind the double barbed-wire fence the open fields spread wide open.

More soon,

Nir

I mention Revital’s story to my friend Deborah. I had no idea that she had a personal connection to the kibbutz. Thirty years ago she’d been one of those idealistic American Jewish youths looking for a new way of living, communally, in Israel. Deborah lived on Kibbutz Metzer in 1972, the same place, a very different time.

CONVERSATION W/ WOMAN WHO LIVED ON KIBBUTZ METZER IN 1973

I don’t think there are very many places where the Arab village and the kibbutz are truly living side by side. And there always was a really good relationship between village and the kibbutz. And the very first at had coffee was in the village at Muhammad’s mother’s house. Of course, in Arab house you are always offered coffee and you can’t say no and I have never drunk a cup of coffee before.

The kibbutz was built literally on the dividing line of the West Bank. In fact the and the banana groves we used to work in the banana groves sometimes picking the bananas we were actually in the west bank. And the way that the… the road bet Haifa and Tel Aviv was here. If you went left, you went straight into the village of Metzner and if you went straight and kind of to the right you went to the Kibbutz Metzer.

If the Arabs from the village came to the kibbutz there needed to be a reason for them to come to the kibbutz. Where as if the villagers walked passed the village – if the kibbutzniks walked passed the village they were just walking towards the bus stop.

Going into the west back then was an incredible thing.

[How?]

It was like going to a different country. I mean this was 1973 there was barely – they weren’t even occupied. I mean they were occupied in that Israel controlled them militarily but there were no Israelis there. I mean look at all these villages. There are so many villages. There’s tons and tons. And I bet most of them are gone. This is all around Jerusalem.

I don’t think that they’re anymore, this is all Israeli now.

And when they build this fence between the West Bank and Israel it will probably run right through those banana plantations unless they do what they probably will do which is make a road around them so that the Israelis get the banana plantations and the Arab farmers wont be able to cultivate their crops

Listen to this: Israeli -Arab armistices in 1949 partition. Palestine. Since June 1967, Israeli forces have occupied Sinai, Gaza, all of Jordan and most of the Jordan River and a small area in southwest Syria. So of course it is all of Jordan and most of the Jordan River that we are talking about. And Metzer was just on that border.

PHONE CONVERSATION BTWN NIR AND LYNNE

Hello Lynne. HI NIR. I finally met Avi, Revital’s husband, at the Kibbutz. YOUR KIDDING. Yes, he brought her tapes, and I brought my camera. YOU ACTUALLY MET AVI, YOU ACTUALLY GOT THE FILMS. IT’S BEEN A YEAR SINCE… THAT I’VE BEEN WAITING. I saw the kibbutz, the house was living, where she was killed. I CAN’T BELIEVE THIS.

INTERVIEW WITH AVI OHAYON

She was the kind of person that had to find the exactly right path for her that the way of life that she believes is the only way of life that is right. That is the only way of life that is correct and right for her to live in. And so she struggled are her life to create that path to be able to have a career and to have the most amazing children and to make a path that nothing would come – would hurt the other goal.

Her movie was about three girls that didn’t know each other that met in a coincidence one day. And they went together on a trip and it was the first time that each one of them realized that she doesn’t like what she does in her life. All three of them are living a life that someone else dictated to them. One of them was a married woman with 3 children. The other one had a shop. The third one was a secretary. They had to help one another and by that they understood about themselves.

Her movies will not give an answer at the end of the movie but will make you put a question mark in the right places. To think ok I saw but who do I relate to, who do I think I behave like, who do I think make the right decision for me as a viewer. And even more I think that the goal, as I know Revital, that whatever choice you make it’s the right choice.

September 10, 2003

Dear Lynne

Now I’m testing my senses and trying to capture images of my living environment. Sending it oversees to you. Like caging wild animals.

Nir

Yossi: So where would you like me to begin?

Lynne: Maybe who she was.

Yossi: Who she was? I think I realized who she was only after the funeral. There were SO many people…. throughout sitting Shiva.

I keep thinking Yossi might have been a man I’ve walked past on the sidewalk, rubbed elbows with on the subway. If I could actually hear the tragedy of a violent death caused by hate, the gunshot, the explosion, months later in the minds of a family-member, would I be able to detect such an emotion as I sit next to a stranger? I ask him why Revital chose to live so close to the border of the West Bank. I’m contemplating the degrees by which we measure danger. She might have wondered why I stay in New York City with my 2 girls after September 11th. What does it mean to call a place home, like a squirrel burrowed in a tree she knows is just a leap from the hole of a fox.

DAY CARE CENTER AFTER FUNERAL, CREATING A MEMORIAL, CANDLES

TRANSLATION FROM HEBREW

TEACHER: Yesterday I was at the funeral for Matan and Noam. Do you know what a funeral is? The word funeral comes from Lelavot, to accompany. We accompany the dead to their grave. Then we bury them.

BOY: A grave is only in the ground.

TEACHER: What does a grave look like? When you bury someone what do you cover it with?

GIRL: A grave is only made of dirt. If someone dies, you don’t leave them at home. There is too much blood.

BOY: You need to dig a hole in the earth. You cover them with dirt just like you cover carrot seeds. Then you put a sign with their names on the grave.

BOY: I saw the terrorist who killed Noam and Matan on TV. Do you want to hear something about the terrorist? He has a brain of a chickadee and the common sense of a dog. LAUGHTER

I met a girl in summer camp in 1971. She was tall, lanky with blonde hair, very nice, quiet. One August afternoon, around my birthday, she confided to me that her father had been shot down in an air force plane in Vietnam. It was as if she’d told me that she had leprosy. I was so terrified I really couldn’t talk to her, or even stand near her, the rest of the summer.

TEACHER: We have things of Matam and Noam here. We have their dolls, their pacifiers, their drawings, tooth brushes.

CHILD: We have to take the stuff out so we can remember them, so that we don’t worry about them.

GIRL: If I take things out it will make me sad.

BOY: We are going to see the story again tonight on the news.

September 12, 2003

Lynne,

Now is the month of Elul, a time of repentance and reconciliation before Yom Kippur.

Such an intense period of prayer – -Selihot — a request for forgiveness.

There is this custom of lighting Ner Neshama (a soul candle) on Yom Kippur. A candle for the dead that lasts for 24 hours.

Yona Wallach wrote about it:

“My awareness is fading away, like a soul candle ….”

I like the way her poems sound in Hebrew.

(Yamim Noraim — DAYS OF AWE)

I wonder what this all means to you.

Soon,

Nir

Today I started to read Allen Ginsberg’s Kaddish. Do you know it? I got the book a long time ago for 99 cents on St. Marks Place. Why did I start reading it today all of a sudden?

VOICE OF REVITAL COMFORTING HER SON IN HEBREW

AVI: She was lucky to go with them and maybe even luck was not the issue here because there’s no other way, there’s no other possibility that they would have gone without her or that she would have one without them. All three of them were one all the time.

February 24, 2004

Nir,

This morning I finally met Revital’s mother at Yossi’s apartment here in New York. She offered me a delicious cup of berry tea she brought from her home in Haifa. It’s divine, with such a powerful aroma like walking in a field.

Lynne

�REVITAL’S MOTHER IN HEBREW: She believed that everything that is happening was not supposed to happen. That expressions from our nation could show the world that this is nonsense. This isn’t supposed to be happening. It’s very important that peace pervades. She took care of people at work, in the army. She wanted everything to be perfect.

YOSSI (R”S BROTHER): I asked her how she could possibly live in this country. I mean this constant stress is unbelievable. So she just created her own bubble and she used that bubble with her two little boys and she blocked herself to the environment and she moved to that little kibbutz where she has a little garden and they plant trees and flowers and she doesn’t read the news, she doesn’t watch the news,. I mean she doesn’t watch the news. And unless something close happenedd to them, the rest she is just oblivious to it.

That Passover was, was one of the bloodiest times of the Intifadah, the uprising. There was a terror attack almost on a daily basis, sometimes two times a day. How can you raise kids in this kind of atmosphere. They knew so much about what was going on.

She tried to keep herself separated from this whole craziness and yet she ended up being a casualty of war.

MOTHER: Well first of all the way it happened, he, the terrorist, managed to jump into her most intimate room where she was with her kids. She covered her kids with her body. They don’t want to give us the details. We didn’t see the pictures but what we heard was that she was screaming “Don’t kill them, just kill me!” That’s what the neighbors heard. They found her hugging her kids. I think that was the most tragic image, the one that moved the world. The Minister of Media sent that image around the world.

As a teenager, Revital used to go to the Judah Desert to learn about and photograph foxes and wolves. She was so interested in science. We thought that would be the direction she would go.

September 23, 2004

Lynne,

I keep growing here in Israel. Many things I would like to talk to you about. Did you know that the murderer of Revital was killed by the IDF, the Israeli Defense Force? I actually saw Avi Ohayon, Revital’s husband a few times on TV today.

The circle of grief hasn’t finished turning.

I learn and watch new aspects of reality every day. By living in my small environment I hope to generate a wave of sanity. I start inwards then I hope to get it out there one day.

Hope you are well,

Nir

Dear Nir,

I’ve been to Bosnia and Vietnam with my camera, made films there, looking for tell-tale signs of conflicts I’d never known. But those wars were over by the time I got there.

The difference between the peacefulness of the images you’re sending me and the hostility simmering outside the frame is so apparent to me. Are you trying to protect me, Nir? . The bombing of a tourist hotel in the Sinai a few months ago, the destruction of a home in the West Bank, the explosion yesterday in a Tel Aviv nightclub. Lynne

December 12, 2004

Lynne,

Today is Tu Bishvat, the birthday of the trees. An almond tree is blooming on Rotchild boulevard. It has white flowers and a really sweet smell.

I think that the olive tree grows very slowly. It has a long history here in Israel. Some are very old. Some have been here since before the country was even established. It has a very unique trunk, like sculpture, the color of bronze. The branch itself is mentioned in the Bible.

In the forest there are Cyprus and Pine and it seems as if they have been there forever, but in reality they were planted by a foundation. The making of a forest. A nation established. The concept of a nation to stay. Marking territory.

My bible teacher used to point to Jewish law: if a soldier needs to cut down an olive tree, he must have permission from a very highly ranked officer in the army.

In my head I compare the status of a person and a tree…. you don’t need special permission to shoot someone if there is a threat, but you need high authority to damage an olive tree. Olive is the color of the soldier’s uniform.

Nir

AVI: My children were four and five. They loved to hear the Muezzin from the village next to Metzer.

�BROADCAST ABOUT WEST BANK WALL

Some go through the bottom others go over the top or squeeze through the middle of the wall Israel is building to stop suicide bombers from getting into Jerusalem.

So far, all the wall does, say the Palestinians of Abu Dis where the wall cuts their village in half, has ruined their lives. Israel’s plan is a combined wall and fence to run about 350 miles around most of the West Bank patrolled by police chiefs this part will run 38 miles near eastern Jerusalem with electronic sensors. Rada Audi who has breast cancer must sneak through the wall to get to her clinic and to get to work but it will get worse one day she won’t able to even do that.

RADA: They are forcing us to hate them and it is a very bad thing.

BYSTANDER (off camera): There has to be a better way than to split a village

Eventually the wall won’t only split Abu Dis and it won’t only cut Palestinians off from Israel. Through large parts of the West Bank it will cut off Palestinians from Palestinians.

This is the land that devours it own, I’ve read and read again in the Bible. The land of hyenas and jackals and doves, perpetually dry or consumed by water. It is a land I know now, but only anciently. At last, I can follow the green line with my finger, but I have yet to feel its actual bumps and crevices.

Hello Lynne

When I was 14 yrs old, I took a trip with a summer camp to Ein Gedi, a nature preserve in the desert, next to the Dead Sea. Our bus stopped at a slaughter house to pick up a brown cardboard box filled with little, weak, yellow chicks. As the sun was going down, we drove into the wilderness of the desert. In the darkness, we let the chicks loose and stepped away. Then we illuminated the area with light and waited with binoculars. The night animals started to show up. First the wolves, then the foxes, and when they were done the hyenas and the vultures came to eat the leftovers.

Nir

I’ve been reading the Bible incessantly, compulsively, looking for those few phrases that might give credence to a landscape that makes normal people go mad.

.

AVI OHAYON: Last summer they went to the seashore with Revital. There was a fight between Arabs and Israelis at the beach. One of the guys from the Arab group was hurt and he was bleeding. He ran to the parking where Revital and the children just arrived. She immediately started to call; she rushed him in the car and took him to the hospital. When I heard about it, when she told me what happened, I asked her, “Are you crazy?”

NEWS REPORT FROM CONFLICTS BTWN ISRAELIS AND PALESTINIANS

REVITAL’S MOTHER: She really didn’t have a childhood. She missed adolescence. She matured very quickly. At our house there was no middle ground, she had to do everything fully. No easy ways to do things. No compromises.

February 27, 2005

Nir,

I’m watching Haifa now, imagining Revital’s childhood in this city, the place where you’ve told me a Jewish girl and an Arab girl might have played together.

Bombs are exploding everywhere this afternoon. The sound is deafening but I can’t hear a thing. Israel. Istanbul. Iraq. Any shake-up on the surface of the earth dislodges my sense of equilibrium.

Newspapers drape us with the numbers of another person’s death. When scanning a page of horrors, I do not grope for mirrors. An open window onto the spectacle of killing. A gust of wind and I almost smell it.

Lynne

TEACHER: Nora can’t have Matan and Noam’s things under her bed. At a certain point, we have to separate from Matan and Noam. We have to collect their things. What can we do with them? What are they?

CHILDREN: Animals

TEACHER: We will have to ask their father what he wants to do with them. What are we going to do with their sheets, pillows, drawings? Do you have any ideas?

GIRL: Give them to their father so he has them in his house.

We can’t leave them outside.

AVI:The pain is so big but still you do not know where to put it ‘ cause you don’t know that kind of pain. You never felt if before. I never felt it before. I couldn’t relate to it in myself because I didn’t know where to put it. It is a different kind of pain you don’t know from before..

R’S MOTHER: During the whole month of sitting Shiva and also during the funeral, it always rained, but every time we arrived at the grave, it would stop raining.

YOSSI (R’S BROTHER) : It happened to us in the funeral. It happened to us in the seven days of the unveiling and it also happened in the 11 months. And the day of the anniversary, we went to the cemetery, the rain stopped. three pigeons actually that landed on the stone, the tombstones, while we were there, while we were saying the prayer for the anniversary… it was like a message from our sister, sending three doves onto the tombstone…

March 1, 2005

I‘ve stopped watching television all together, Nir. I have a rock to put on her grave. I arrive in Tel Aviv on Wednesday at 3:55 PM. Lynne

TITLE:AS I AM HEADING OUT THE DOOR TO THE AIRPORT, MAYA ASKS ME “IS THERE A WAR IN ISRAEL, MOM?”

“NO, NOT TODAY.” I TELL HER.

This is the land that devours it own, I’ve read and read again in the Bible. The land of hyenas and jackals and doves, perpetually dry or consumed by water. It is a land I know now, but only anciently. At last, I can follow the green line with my finger, but I have yet to feel its actual bumps and crevices.

Hello Lynne

When I was 14 yrs old, I took a trip with a summer camp to Ein Gedi, a nature preserve in the desert, next to the Dead Sea. Our bus stopped at a slaughter house to pick up a brown cardboard box filled with little, weak, yellow chicks. As the sun was going down, we drove into the wilderness of the desert. In the darkness, we let the chicks loose and stepped away. Then we illuminated the area with light and waited with binoculars. The night animals started to show up. First the wolves, then the foxes, and when they were done the hyenas and the vultures came to eat the leftovers.

Nir

I’ve been reading the Bible incessantly, compulsively, looking for those few phrases that might give credence to a landscape that makes normal people go mad.

.

AVI OHAYON: Last summer they went to the seashore with Revital. There was a fight between Arabs and Israelis at the beach. One of the guys from the Arab group was hurt and he was bleeding. He ran to the parking where Revital and the children just arrived. She immediately started to call; she rushed him in the car and took him to the hospital. When I heard about it, when she told me what happened, I asked her, “Are you crazy?”

NEWS REPORT FROM CONFLICTS BTWN ISRAELIS AND PALESTINIANS

REVITAL’S MOTHER: She really didn’t have a childhood. She missed adolescence. She matured very quickly. At our house there was no middle ground, she had to do everything fully. No easy ways to do things. No compromises.

February 27, 2005

Nir,

I’m watching Haifa now, imagining Revital’s childhood in this city, the place where you’ve told me a Jewish girl and an Arab girl might have played together.

Bombs are exploding everywhere this afternoon. The sound is deafening but I can’t hear a thing. Israel. Istanbul. Iraq. Any shake-up on the surface of the earth dislodges my sense of equilibrium.

Newspapers drape us with the numbers of another person’s death. When scanning a page of horrors, I do not grope for mirrors. An open window onto the spectacle of killing. A gust of wind and I almost smell it. Lynne

TEACHER: Nora can’t have Matan and Noam’s things under her bed. At a certain point, we have to separate from Matan and Noam. We have to collect their things. What can we do with them? What are they?

CHILDREN: Animals

TEACHER: We will have to ask their father what he wants to do with them. What are we going to do with their sheets, pillows, drawings? Do you have any ideas?

GIRL: Give them to their father so he has them in his house.

We can’t leave them outside.

AVI:The pain is so big but still you do not know where to put it ‘ cause you don’t know that kind of pain. You never felt if before. I never felt it before. I couldn’t relate to it in myself because I didn’t know where to put it. It is a different kind of pain you don’t know from before..

R’S MOTHER: During the whole month of sitting Shiva and also during the funeral, it always rained, but every time we arrived at the grave, it would stop raining.

YOSSI (R’S BROTHER) : It happened to us in the funeral. It happened to us in the seven days of the unveiling and it also happened in the 11 months. And the day of the anniversary, we went to the cemetery, the rain stopped. three pigeons actually that landed on the stone, the tombstones, while we were there, while we were saying the prayer for the anniversary… it was like a message from our sister, sending three doves onto the tombstone…

March 1, 2005

I‘ve stopped watching television all together, Nir. I have a rock to put on her grave. I arrive in Tel Aviv on Wednesday at 3:55 PM. Lynne

TITLE:AS I AM HEADING OUT THE DOOR TO THE AIRPORT, MAYA ASKS ME “IS THERE A WAR IN ISRAEL, MOM?”

“NO, NOT TODAY.” I TELL HER.

NIR & LYNNE TOGETHER

NIR:A group of a hundred or more religious men are marching down the street, chanting loudly. Can you hear it? The time is 6pm on a Friday evening, quite an unusual sound to hear at this time, something alarming about it, like a revolution.

Time is so poignant now. The right wing blocked a highway on Tuesday ,

Tomorrow the left wing is having a support demonstration at city hall.

LYNNE: It is warm, so peaceful in Tel Aviv, and yet as the sun comes down I hear that unusual chant of prayer from the street. What does it mean?

YOSSI

We just finished the 30 days mourning. It was raining, it was like a message from my sister, sending three doves into the tombstone. By the time we got back home, we received a phone call from the military spokeswoman who gave us the good… I don’t know if it’s good or bad, gave us the news that the murderer who killed my sister and two nephews was ambushed and killed.

AVI: I think Revital knew about life, knew what’s important in life, what I only learned after they went. I think I had to suffer the loss of all three of them to start understanding what she already knew. It’s like the place you’re coming from, trying to do something that is very personal. When you see those pictures coming from Israel each and every day, you stop looking at it as something that happens to people; and you start approaching it as a big thing that goes over in a small corner of the world, but there’s people involved.

If the geographic farness makes you numb and you can’t feel it, it will reach you too. It will happen in Iraq, in Iran, in Syria, in New York, in Madrid, in Ireland, and it will only stop when we start going back to our feelings, and try to relate to the fact that there is a person that could have been my friend, that could have been the brother or sister of someone who just rode with me on the subway. It could be me.

Dear Nir,

I cannot remember if the sun was shining or if I was wearing a sweater, or if I had a cup of tea in my hand when I picked up the newspaper on November 12, 2002. I only know that I saw anguish. My daughters heard the story of Abraham and his two sons this morning for Rosh Hashonah .

LYNNE’S DAUGHTER TELLS STORY OF ABRAHAM, SARAH, HAGAR, ISAAC AND ISHMAEL:

NOA: Abraham wanted a child so badly. He was 100 years old as was his wife Sarah, and there didn’t seem to be a chance. So Abraham decided to take matters into his own hands. He had a son with Hagar, the Arab maid. They named him Ishmael. Then, miraculously, Sarah too became pregnant and gave birth to Abraham’s second son, Isaac. Sarah was jealous of Hagar whose son would always be able to lay claim to being Abraham’s first born. So Abraham asked God to send Hagar and her baby boy to a far off land. God said to Abraham: “It is through Isaac that your offspring will be reckoned. I will make the son of the maidservant into a nation.”

NOA: Since his son had to go in the desert, he must have been really sort of mad.

LYNNE: Who was mad?

NOA: Abraham.

LYNNE: Abraham was mad…

NOA: …because his son had to go in the desert.

LYNNE: Yeah, and how do you think the brothers’ felt that they were separated?

NOA: How do you think?

LYNNE: I think they could have gotten along and lived in the same house together even though they both had different mothers.

NOA: Did, umm, did, did,…who sent them into the desert?

———-

All the best, Lynne

CREDITS

�