Working with Humanity Now: Direct Relief Program

Athens & Thessaloniki, Greece

July 2 – 12, 2017

Lynne Sachs

I am in Greece with my sister Dana Sachs, my brother-in-law Todd Berliner and friend Jennifer Maraveyais, as part of Humanity Now: Direct Refugee Relief program. While in Athens, I am teaching English and running a sunprint art workshop at Orange House, a center for refugees “with a focus on unaccompanied minors, single women, and mothers with children. United with volunteers from around the world, its guiding purpose is to assist refugees who are searching for a safe haven.”

I am in Greece with my sister Dana Sachs, my brother-in-law Todd Berliner and friend Jennifer Maraveyais, as part of Humanity Now: Direct Refugee Relief program. While in Athens, I am teaching English and running a sunprint art workshop at Orange House, a center for refugees “with a focus on unaccompanied minors, single women, and mothers with children. United with volunteers from around the world, its guiding purpose is to assist refugees who are searching for a safe haven.”

The first day, I taught English to two young fellows. This actually gave me the opportunity to hear their personal stories as a way to practice speaking. The first man was an Arabic-speaking Palestinian nurse who was about 30 years old. His name is Mohammad and he comes from a family of nine, all of whom are educated and live in Aleppo, Syria. They seem to have careers, like engineers, and administrators, etc. He is the only one who left, and he did this after 1 1/2 years in jail in Syria. We spent about five minutes talking about President Assad because he kept using the word “president,” and then I finally figured out that he was trying to say “prison.” After his release, he went to Turkey first and then tried to get on six different boats from there before he was able to make his way to Greece. By the way, I was correcting his English all the way through his story. He was giddy to learn from someone who was so attentive to his speaking, and he was able to make the corrections on the spot. I often interrupted his very dramatic story to explain how complicated English prepositions can be.

I also met a 19-year-old Afghan man. I gleaned from his very few words of spoken English that he is from a small town near Kabul, Afghanistan, speaks Farsi, is 19, and was born on Feb. 21. If I understood correctly, he has never been to school, so I was even more impressed by how determined he was to use his language workbook. His notebook indicated that he could tell the difference between the past and the past perfect. Impressive. Just from these two interactions, I learned so much about how developed Syrian society is (the intensity of the war there has not been as long) and how fragmented and chaotic Afghan society is (generations of war).

By the second day of my art workshop at Orange House, both children and parents participated while they were waiting for their own English, German or French lessons (depending on where they are anticipating having their families resettled in the future). One of my student participants is a young man named Anas Saidi from Syria who speaks English fluently and has already been resettled in Germany. He had returned to Athens for a few weeks to volunteer. He told me that he is an aspiring filmmaker, and that he wants to make a film about his own journey from Damascus, including the two weeks he lived in the woods in transit. We talked a lot about films we had seen and our own work. He is living in a small German town, so he is a bit frustrated because this is a place where actually very few people speak English and there is no film community. Then I impulsively asked if he is interested in coming to the United States, to which he answered very sweetly, “It is not possible for me to come to the US now.” Oh yes, how could I forget? You can see him holding his amazing sunprint below. Here are several images from the workshop. This is the translation of the Arabic words in Anas’s image: Love, Bread and Freedom.

By the second day of my art workshop at Orange House, both children and parents participated while they were waiting for their own English, German or French lessons (depending on where they are anticipating having their families resettled in the future). One of my student participants is a young man named Anas Saidi from Syria who speaks English fluently and has already been resettled in Germany. He had returned to Athens for a few weeks to volunteer. He told me that he is an aspiring filmmaker, and that he wants to make a film about his own journey from Damascus, including the two weeks he lived in the woods in transit. We talked a lot about films we had seen and our own work. He is living in a small German town, so he is a bit frustrated because this is a place where actually very few people speak English and there is no film community. Then I impulsively asked if he is interested in coming to the United States, to which he answered very sweetly, “It is not possible for me to come to the US now.” Oh yes, how could I forget? You can see him holding his amazing sunprint below. Here are several images from the workshop. This is the translation of the Arabic words in Anas’s image: Love, Bread and Freedom.

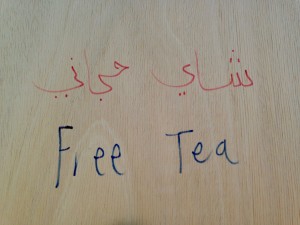

In the late afternoon, I went to a community center where we made 60 turkey sandwiches with some other volunteers — three British nurses, two 17-year-old Iraqi boys, one Iranian boy who is obsessed with film history, and the Albanian male organizer. A group of six of us walked around the center of Athens giving out sandwiches and cups of tea to homeless people, all of whom the Albanian man knows by face since he does this three times a week. The homeless people are mostly, but not all, refugees from neighboring countries in flux. One young Pakistani man was sleeping on a piece of cardboard in a city park. He had a fabulous, bouffant Elvis-like hairstyle, and skinny jeans, but he seemed quite delirious and had some sores on his arm, so one of the nurses in our group cared for him right there on the ground.

The other morning, I got up early and walked to the top of the Acropolis. There are, of course, thousands of tourists at this most famous spot. I am not sure how many of them realize the human turmoil that is swirling around them. It would be easy not to notice, strangely enough.

One day, we visited an abandoned farm about an hour and a half from Athens that could become a home for two refugee families who have recently arrived here. There were figs, quince, and pears growing among the shambles. As fecund as the land appeared to be, it looked to me as if the possible renter was wondering how he and his family might make a go of it in a rural area, far from their community and the access that a city allows. The project is an experiment in home building for people living in squats or on the street or in a camp, offering something new and full of possibility, like a new “used” shirt that is clean and ready-to-wear but somehow you feel may not suit you, that everyone says makes you look so good, but you know you will never feel comfortable wearing. We took a walk up a hill full of sage bushes and olive trees to a small bee hive that we were told had produced 12 kilos of honey. Everyone was so impressed, but perhaps learning this new skill might be intimidating to the family, perhaps they are scared of bees. I am not sure the father in the family was convinced that the property was really salvageable, at least for him. And so, the search for a home continues. Here you see me holding freshly picked herbs near the farm and sinks from a refugee camp that will be reused somehow. Everything is recycled. Everything.

One evening, Dana, Todd and I ate dinner with some Palestinian friends of hers. There was a wonderful mom from Syria who has five adorable, perky children. About a year ago, she traveled to Greece from Aleppo, Syria all by herself on a boat with a woman smuggler because her husband had already escaped the war with their oldest child and she and the younger ones were hoping to follow them. So far, that has not worked out. Through Dana’s translator, I learned that her family is originally from Palestine but that her grandparents had been forced to leave in 1948, at which time they made their way to Syria. The other man at our table comes from Gaza where his entire family still lives, but they are not able to leave and he is not able to return since Gaza is currently completely closed off. Both situations are directly connected to the history of Israel/ Palestine and, in many ways, were deeply disturbing to me.

In Greece, at least for me on this trip, you are asked to imagine how a place might have looked when there were once people there. Imagine, in the shadow of the columns at the Arcropolis, a symposium of supine thinkers relaxed on marble benches in 204 B.C.E. Imagine a thousand refugees in tents camped out on the grounds of a gas station near the village of Idomeni in the winter of 2016. Dana came to the Idomini refugee camp for two weeks in 2016 to help serve food and deliver much-needed clothing to thousands of Syrian men, women and children living in tents. Forced from their country by the ravages of a cruel chemical war, these displaced people were seeking asylum in Europe, attempting to pass through Greece across the northern border. They were stopped head-on just before the mountains of Macedonia, and so found themselves in a rural village in Greece that was completely unprepared for the magnitude of such an international crisis. Anyway, Dana was so moved by her witnessing of this situation that a year later she brought me and her fellow Humanity Now friend Jennifer back to Idomini, which is about an hour and a half north of Thessaloniki, to see the site of the camp where she learned to cut herbs, vegetables and other ingredients for savory soups for 5000.

Based on conversations we had over the last few days, I am starting to put together a mental image of this place since all we have now to remind us are a few leftover signs in Arabic and English. We made a special stop at the Eko Gas Station where hundreds of displaced families and single people set up camp. I chatted with a Greek woman who worked in the convenience store on the grounds, wondering how she felt about that intense disruption of their quiet lives. In her very few words of English, she told me how interesting it was for her to watch an impromptu Syrian cook make falafel in her kitchen. She seemed a bit sad that the excitement at the gas station is now over. We drove just a few miles away, down a desolate industrial road and stood outside the barbed wire fence of a smaller camp where the people who could not find passage to other parts of Europe or retreat to the urban squats of Athens are now living indefinitely in Isoboxes in an arid setting where, rumor has it, snakes are reported to rear their ever-threatening heads.

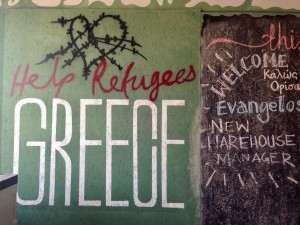

Thessaloniki is a lovely, “bohemian” (as the travel posters promote) city on the Aegean Sea, with a plethora of archeological ruins, student cafés and museums. It has also become a hub around which many refugee camps and volunteer services have appeared in the last two years. If you are not looking for these kinds of places, you would most definitely not find them accidently. We visited the Help Refugees/ Get Shit Done support center where 150 fresh, hot meals are prepared, a gymnasium-size room is filled with completely organized used clothing, wooden bicycles are designed, playground equipment is constructed and more, much more. You can see how this center of activity functions so fluidly, with almost no bureaucracy or NGO-style oversight. When need is determined or problems recognized, this group of about 50 people – mostly in their twenties from all over Europe — responds incredibly quickly.

Thessaloniki is a lovely, “bohemian” (as the travel posters promote) city on the Aegean Sea, with a plethora of archeological ruins, student cafés and museums. It has also become a hub around which many refugee camps and volunteer services have appeared in the last two years. If you are not looking for these kinds of places, you would most definitely not find them accidently. We visited the Help Refugees/ Get Shit Done support center where 150 fresh, hot meals are prepared, a gymnasium-size room is filled with completely organized used clothing, wooden bicycles are designed, playground equipment is constructed and more, much more. You can see how this center of activity functions so fluidly, with almost no bureaucracy or NGO-style oversight. When need is determined or problems recognized, this group of about 50 people – mostly in their twenties from all over Europe — responds incredibly quickly.

Visiting a temporary refugee camp is not like visiting a prison. I know this. I can see that the front gates to the grounds of the two camps on the industrial outskirts of Thessaloniki are not locked. But there are military guards and there is barbed wire along the fence. So, I am trying to reckon with the flow, the ostensibly free movement in and out. I visit two camps today with Jennifer to see what kinds of direct relief they could offer. Are there enough diapers for the babies? Is there any kind of communal space? Is there a playground which would give the children a reason to go out of doors? We are actually able to enter only one of the two camps. In some ways, guards are more tough on foreign outsiders, though it is not clear if they are protecting the “residents” from voyeurs or self-appointed reporters who might take pictures of things they don’t want the world to see. I really don’t know. One of the camps is actually set up inside an old factory, so the ceilings are very high and the acoustics are daunting. Each family has set up their make-shift home in a partitioned area that is about 10’ by 10’. Of course, you don’t look behind the curtain, but it is very moving to see the shoes outside the fabric covered doorway. In the back of the camp, we talked with people in a multi-purpose room where kids were making masks with their parents and college age volunteers from Europe and the US. Next to that was a surprisingly well appointed kitchen with about 20 stoves where women were preparing beautiful meals for their families. To my surprise, all of the tables were pushed to the side wall, clearly not used at all. One person explained to us that Syrian and Kurdish people prefer to prepare their meals on tables that are close to the ground, so it is awkward for them to cook with these donated tables. Luckily, we were walking with Jeni from the Get Shit Done Team. She said she would come back soon to cut the legs off all of the steel tables. No problem. No problem? Really.

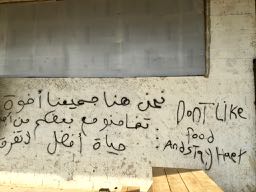

In our visit to another camp outside Thessaloniki, the situation seemed far less supportive and accommodating as revealed by the graffiti about food and water on the walls you can see here. It’s interesting to see the writing in both English and Arabic. Do people write on walls to express their feelings for themselves or for the passerby? Who is your audience? Who is reading? Who is taking pictures? Who is listening?

During my workshop at Orange House, I met Anas Saidi, an outgoing and talented young filmmaker from Damascus who decided to record the step-by-step process of our sunprint workshop with other refugees at the center. While he was shooting his time lapse images (which takes a long time), we had the chance to talk about his escape from the ravages of the war in his country. I asked Anas to write a short bio, and here it is along with his spectacular video:

“My name is Anas Saidi from Syria/ Damascus, I lived in Damascus my whole life. Three years ago I fled to Germany like other Syrian did in a death migration which we don’t know if it’s our last destination or not. I’ve lived and felt the near death experience in every inch of my body and my soul and it has totally changed my life. I am an actor and Filmmaker and my dream is to share everything I’ve seen to the world in a movie. I live in Germany now and I want to study filmmaking and make my dream come true, it’s too hard but I made it here, I make it everywhere.”