Text and design by Ximena Màrquez Orozco

Published in Casi Cielo / Almost Heaven on Medium | May 11, 2024

https://casicielomx.medium.com/biograf%C3%ADa-de-lilith-de-lynne-sachs-una-rese%C3%B1a-f6ddd58fc154

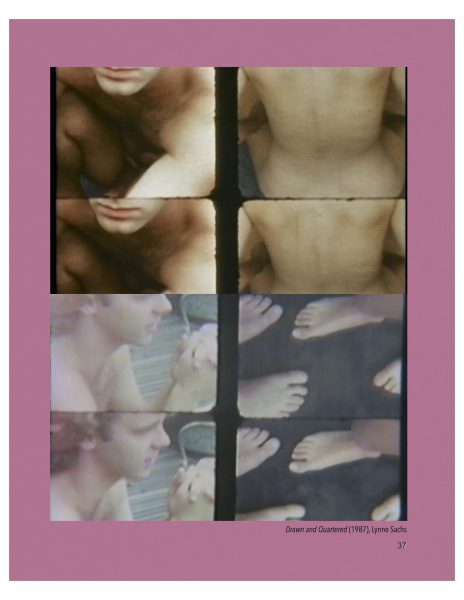

It is this short film that catapults Lynne Sachs and positions her as one of the first feminist filmmakers of experimental cinema.

Faust: who is she?

Mephistopheles: Look at her carefully. This is Lilith.

Faust: who?

Mephistopheles: Adam’s first wife. Beware of her beautiful hair, the only finery that she shows off, when she catches a young man with it she does not let him go easily.

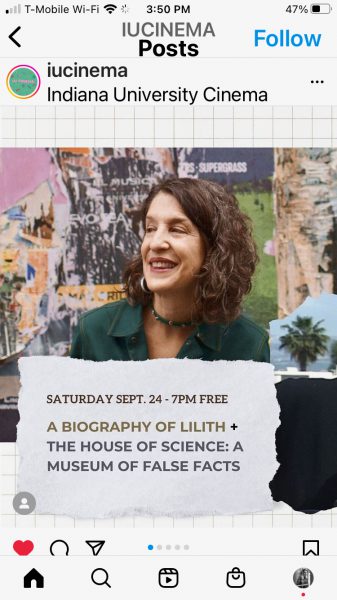

With a unique sensibility and poetic vision, Lynne Sachs is an American filmmaker who challenges the conventions of experimental cinema. Through her works, she explores themes such as identity, memory and family, creating intimate and emotional pieces that invite reflection. Her distinctive style and commitment to innovation have made her a leading figure in the world of independent film. In this review I will talk about one of the most significant shorts of her career: A Biography of Lilith . And I will speak of it as a maximum expression of semantics.

I met Lilith in my last year of high school, at a Catholic school. My approach to religion had been limited to wearing a skirt on Sunday mass until I was 7 years old. My dad stopped believing in institutions and I stopped believing in God. My interest in other beliefs was not above average, but everything changed when I heard her name.

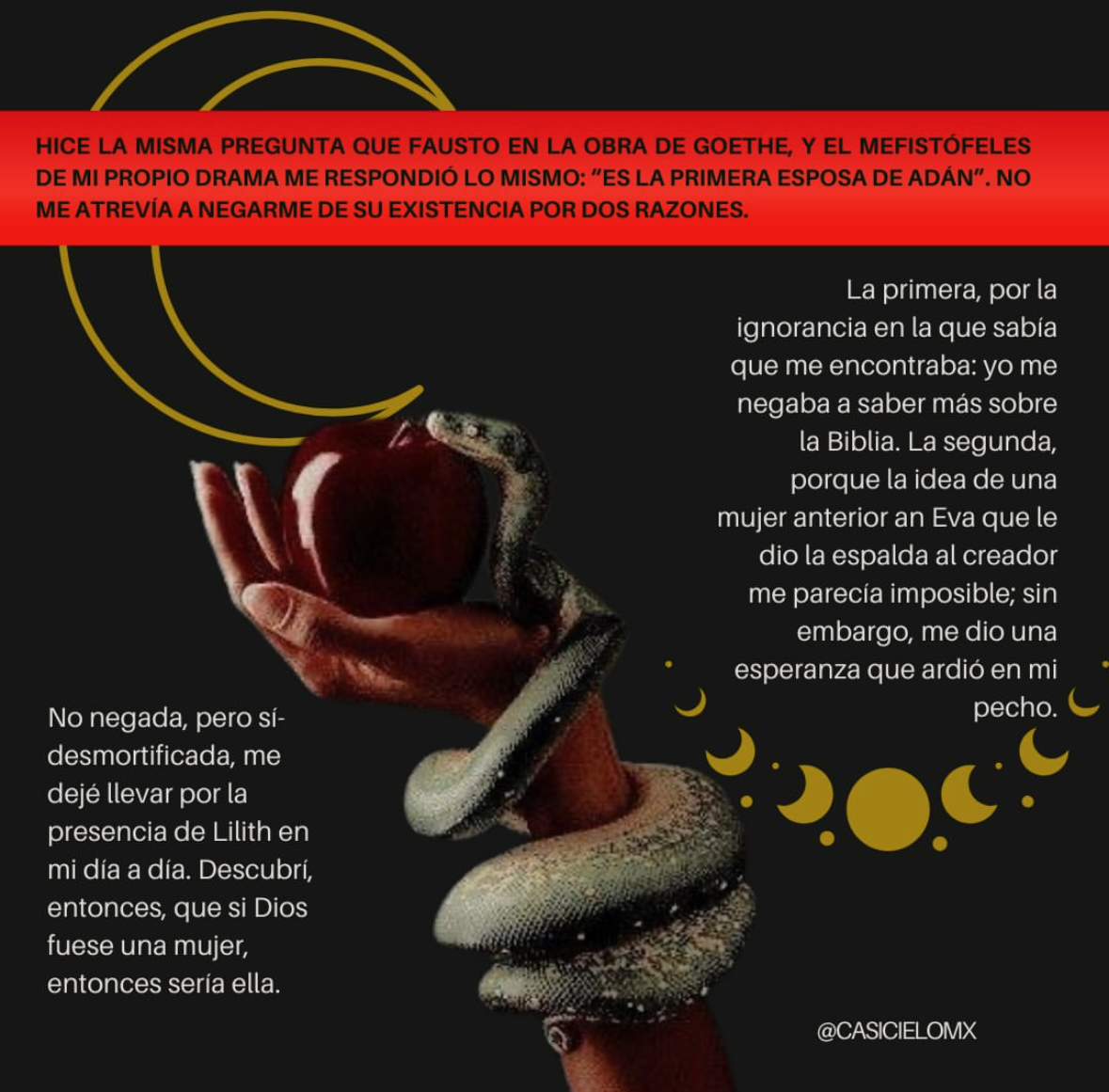

I asked the same question as Faust in Goethe’s play, and the Mephistopheles of my own drama answered the same: “she is Adam’s first wife.” I did not dare deny her existence for two reasons. The first, because of the ignorance in which I knew she found me: I refused to know more about the Bible; the second, because the idea of a woman before Eve who turned her back on the creator seemed impossible to me, however, it gave me a hope that burned in my chest. Not denied, but demortified, I let myself be carried away by Lilith’s presence in my daily life. I discovered, then, that if God were a woman, then it would be her.

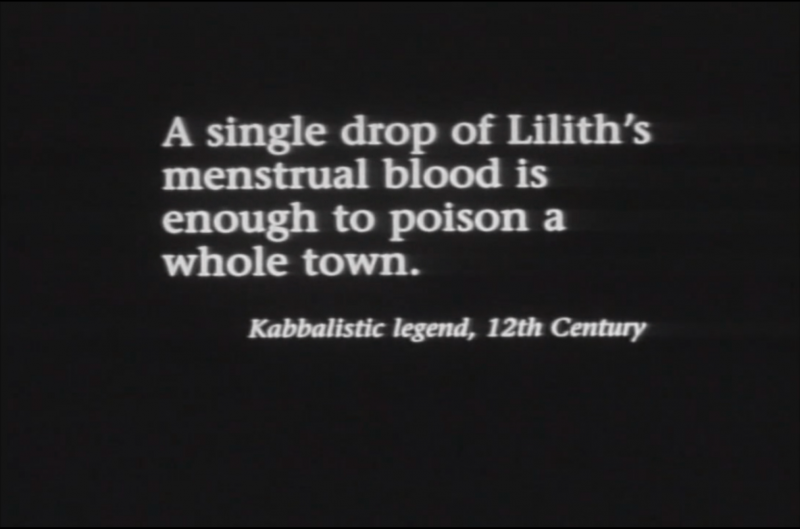

Mentioned by contemporary authors as “the first feminist woman,” Lilith is born from mud. God gives her Eden to him under the same limitations as her successor, but Lilith rebels against Adam’s desires, without him being able to understand that her pleasure also matters to her. Unlike Eve, Lilith is not born from Adam’s rib, so she thinks by and for herself. In the sexual act in which Lilith demands to get on top, Adam does not allow it and she flees to the Red Sea. She meets Lucifer, gives him wings and God gives her an opportunity to return, under the same conditions. Lilith chooses her freedom and, presumably, she is the one who disguises herself as the snake. As part of her punishment, she is condemned to be the infertile woman. Lilith grows and develops in today’s world as the witch who is guilty of the guilt of women of the same condition as hers, as well as the lust of men and also the cause of crib death.

Lilith becomes a fable, the monster who sleeps under the bed of adulterers and impious people, sometimes lulling the crib of a newborn. She is stripped of her own history. Lilith does not appear in The Bible, and yet she exists in the Catholic imagination. She appears for the first time as a literary figure in Goethe’s Faust , briefly (1808 years after The Creation) and begins, at a snail’s pace, to gain visibility . Today, Lilith is one of the greatest symbols of the feminist movement. We carry her in her chest and she burns inside us stronger than ever. It no longer appears only in intellectualism, nor only in books of canonical literature. She becomes Lucifer’s wife in television series, she is painted and sculpted in contemporary art, sociological theses are written under her own name, Drag Queens dress like her on reality shows . Lilith, today, is on everyone’s lips. But, as in Genesis, I think it is important to go back to the beginning to understand the feminist Lilith beyond her sexual liberation.

I remember when I finally discovered what the apple represented in the creation story. Clinging to the little interest she found in Catholicism, I discovered that the apple represents modesty in conservative discourses, which is why Eva covers her naked body. But, this didn’t make sense to me. If Lilith was the daughter of God and had disguised herself as a snake, why prohibit Eve from what freed her? In this same speech, I forgot that the characters in The Bible are, above all, human, and that the ultimate goal of this text is to talk about forgiveness and goodness. I also remembered that it was we who have distorted and polarized belief.

Then I understood that the apple actually represented knowledge, reason, the word. Lilith gave consciousness, first to Eve and then to Adam, about themselves and their surroundings. She gave them free will. And if man is in the image and likeness of God, it is because of his ability to create from the word. If words make reason, and if reason is what differentiates us from animals, then I had no choice but to conclude: if God is a woman, that woman is Lilith. She gave us the gift of knowledge.

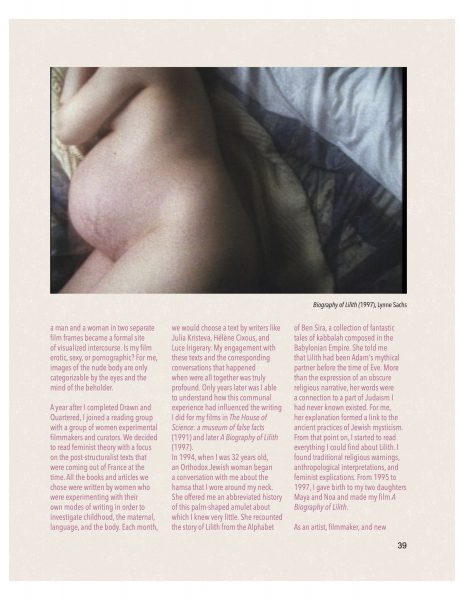

After this journey of reflection, which took me approximately 7 years, I keep coming across Lilith: a challenging woman. And this time she did it under the name Lynne Sachs. She understands, as much as I do (or at least I want to think so), the role that Lilith occupies both today and in history, our history. In her short film, A biography of Lilith, she shows us a bar dancer, Cherie Wallace, whom Sachs interviews about some ideas that, if in themselves are a topic to talk about today, in the early 2000s They were barely placed on the table. She talks about men who take refuge in women from the gallant life, from adoption, about women who belong to that world and who are forced to give birth. But the most surprising thing is that she does it from an intellectual and ethical maturity that little is expected of women in her context (and again, I repeat: much less in the early 2000s).

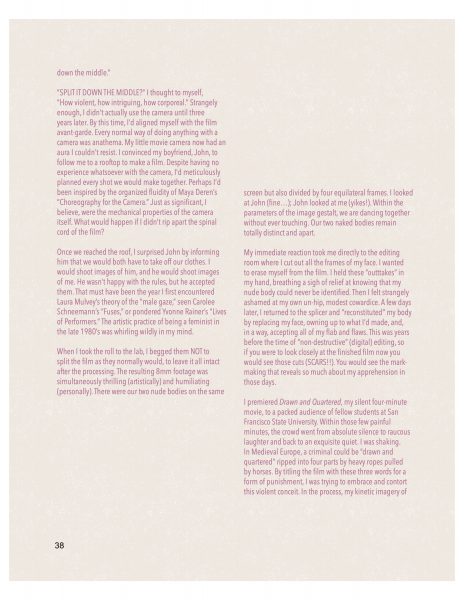

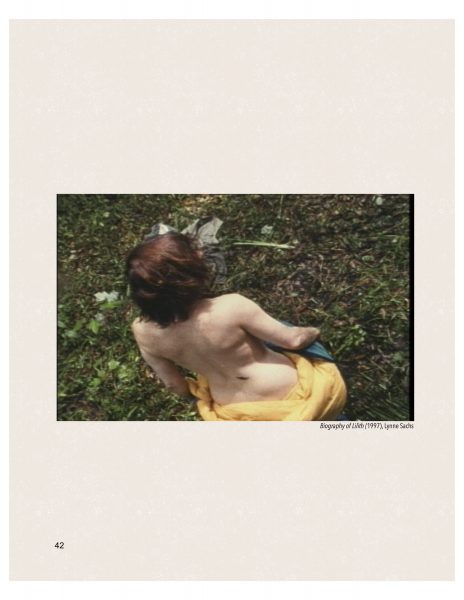

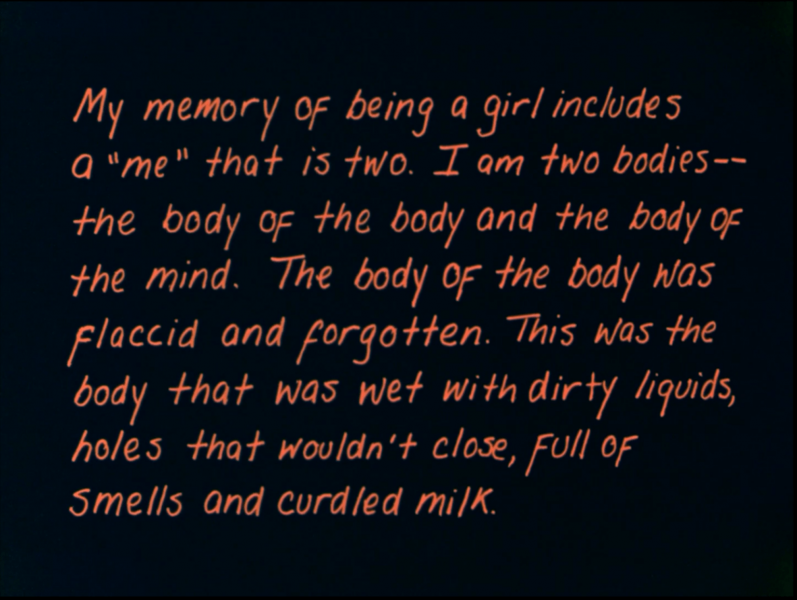

However, it is not the answers or the supposed interview (since we never hear the questions) that we focus on. They only help us understand Lynn’s Lilith. A narrating voice tells the story of Lilith, precisely the one that I have explained previously, but in the images we see representations of her if she belonged to our present day. We see a woman arriving naked to her Eden (which I interpreted as her backyard) full of branches, grass, and a man’s green areas.

So, when the narrator tells us about the relationship between Adam and Lilith, we see this previously naked woman wearing shorts and surrounded by pages, while the man generates approaches that she rejects. She wants to read. But he tries to deny the knowledge. Then, he runs away. Cherie is baptized in the black sea as she discovers her freedom. And somewhere between the present and the past, she becomes a dancer. All this while Sachs places passages of Lilith in the different conceptions that she has of her: witch, lust, stalker, infertile and child murderer. However, as we watch Sachs’ short, Cherie tells the demons accompanying her: “all the children in the world are my children.” Have we not all been guided by the same rule? (Or has teaching made me crazy and I agree with her?: All the children in the world are my children). She doesn’t embarrass us, or I think she shouldn’t embarrass us.

Machismo is not genetic, it is historical. Women and men were not molded by clay, no. We were shaped by our own circumstances. Exiled from Eden, with arms open to knowledge, this is how we wanted to do it. The difference is that women have carried the guilt, the sin… because that is how the beginning of the story tells it. We stay at home and dedicate ourselves to the family. And that is, I believe, our best historical quality: that above all things, we put life first. No, I am not talking about anti-abortion campaigns, but precisely the opposite. Cherie Wallace, in the Lynn Sachs short, basically says that she couldn’t give a child a decent life. She understands her job, she doesn’t intend to leave it, but she understands the weight of carrying a life, a life other than her own and one to which she would not like her baby to belong. So, she gives him up for adoption. Lynn Sachs makes the first approach to Lilith as a human character, as perhaps the Apostles once wanted to make it known.

Lynne Sachs understands the symbology of Lilith as much as feminist women do; not in the archaic text, but in her own life. In her short film Biography of Lilith (1997) we navigate the words of Cherie, who conveys in them a ring of social and emotional responsibility about being a woman in the current era, about the birth, desire and regret of the masculinized man. It is this short film that catapults Lynn Sachs and positions her as one of the first feminist filmmakers of experimental cinema. Sachs also compiles fragments of the fables of Lilith the witch, Lilith the child stalker, Lilith the female demon, Lilith lust, the sinful Lilith, the stormy Lilith, and the Lilith Pandora. Using voice-over narration and Wallace’s voice, he dismantles the metamorphoses of this mythological character, present in the religious imagination, to turn her into her last figure: Lilith, a woman free from male pleasure, a sorora woman who acquires and shares knowledge, woman who liberates her equal, condemned woman and, more than anything, woman of this and all the revolutions that come after.