Note: To watch the full film, click here or scroll to the bottom of this page.

by Lynne Sachs in Collaboration with Dana Sachs

33 min.

“A frog that sits at the bottom of a well thinks that the

whole sky is only as big as the lid of a pot.”

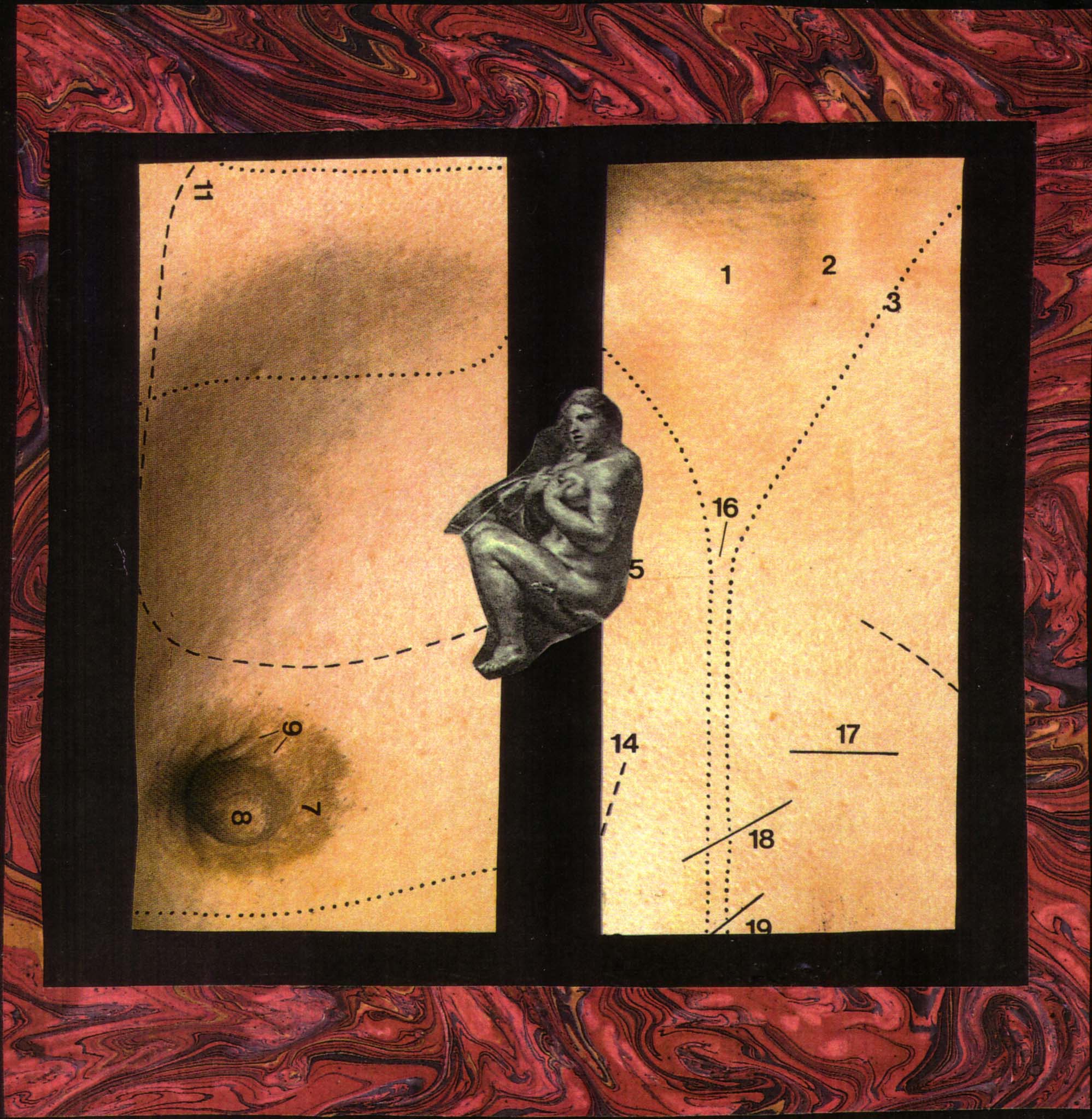

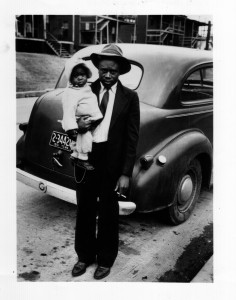

In 1994, two American sisters – a filmmaker and a writer — travel from Ho Chi Minh City to Hanoi. Together, they attempt to make a candid cinema portrait of the country they witness. Their conversations with Vietnamese strangers and friends reveal to them the flip side of a shared history. Lynne and Dana Sachs’ travel diary revels in the sounds, proverbs, and images of Vietnamese daily life. Both a culture clash and an historic inquiry, their film comes together with the warmth of a quilt, weaving together stories of people the sisters met with their own childhood memories of the war on TV.

When two American sisters travel north from Ho Chi Minh City to Hanoi, conversations with Vietnamese strangers and friends reveal to them the flip side of a shared history. Lynne and Dana Sachs’ travel diary of their trip to Vietnam is a collection of tourism, city life, culture clash, and historic inquiry that’s put together with the warmth of a quilt. “Which Way Is East” starts as a road trip and flowers into a political discourse. It combines Vietnamese parables, history and memories of the people the sisters met, as well as their own childhood memories of the war on TV. To Americans for whom “Vietnam” ended in 1975, “Which Way Is East” is a reminder that Vietnam is a country, not a war. The film has a combination of qualities: compassion, acute observational skills, an understanding of history’s scope, and a critical ability to discern what’s missing from the textbooks and TV news.

from The Independent Film and Video Monthly, Susan Gerhard

“Captures the Vietnam experience with comprehension and compassion, squeezing a vast and incredible country into an intriguing film.”

Portland Tonic Magazine

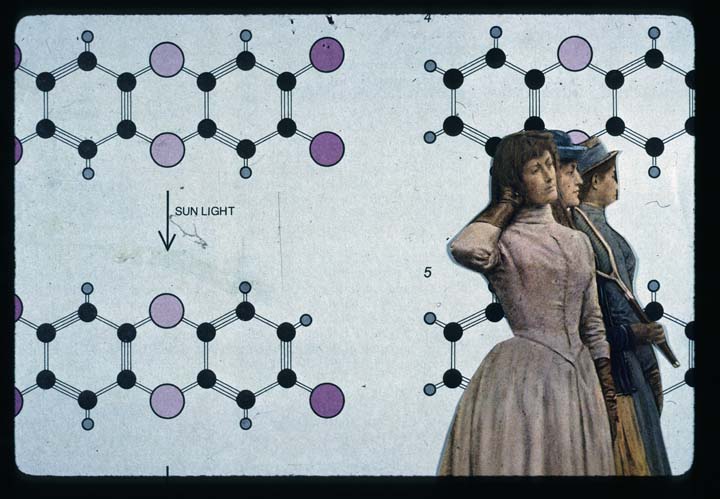

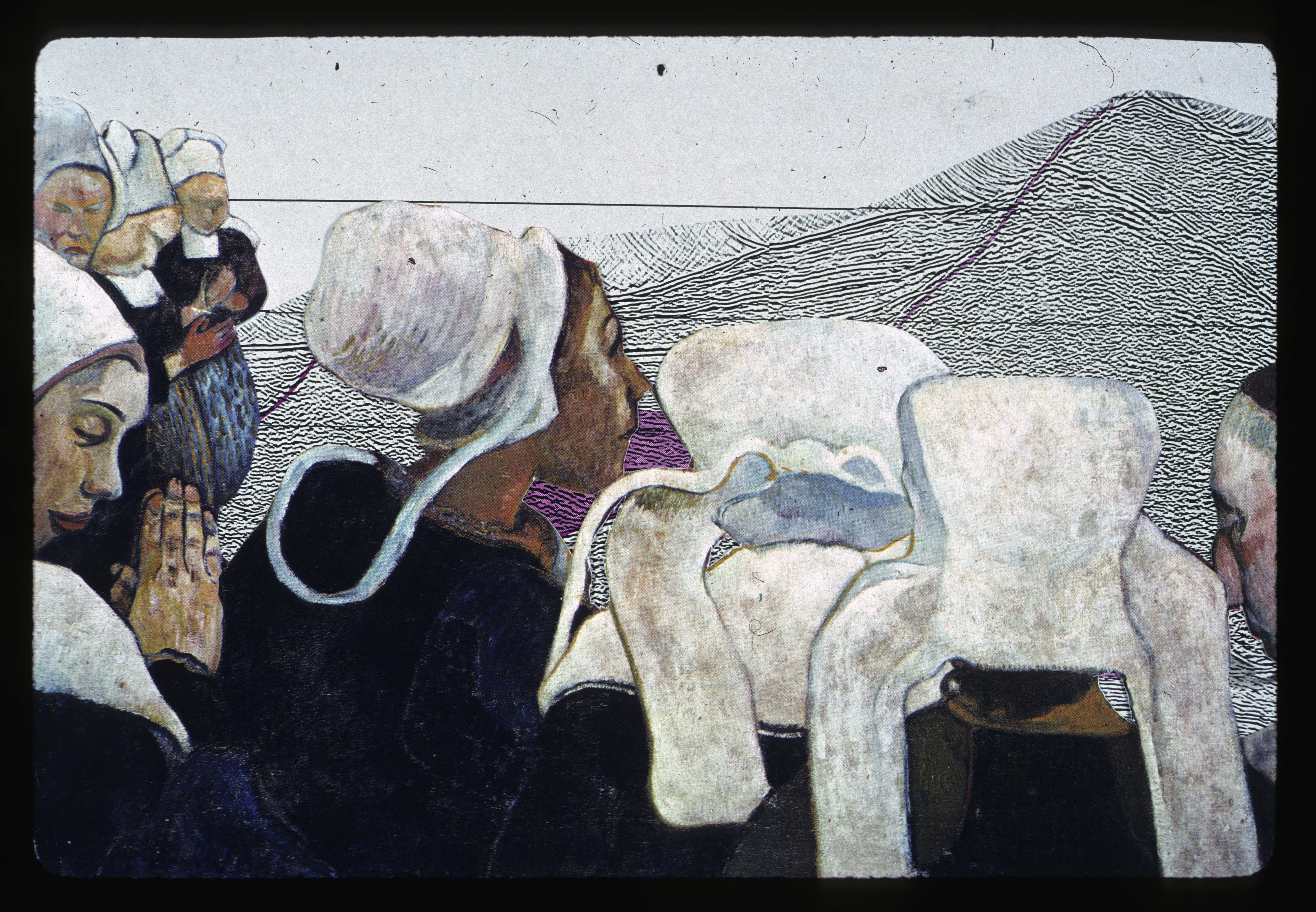

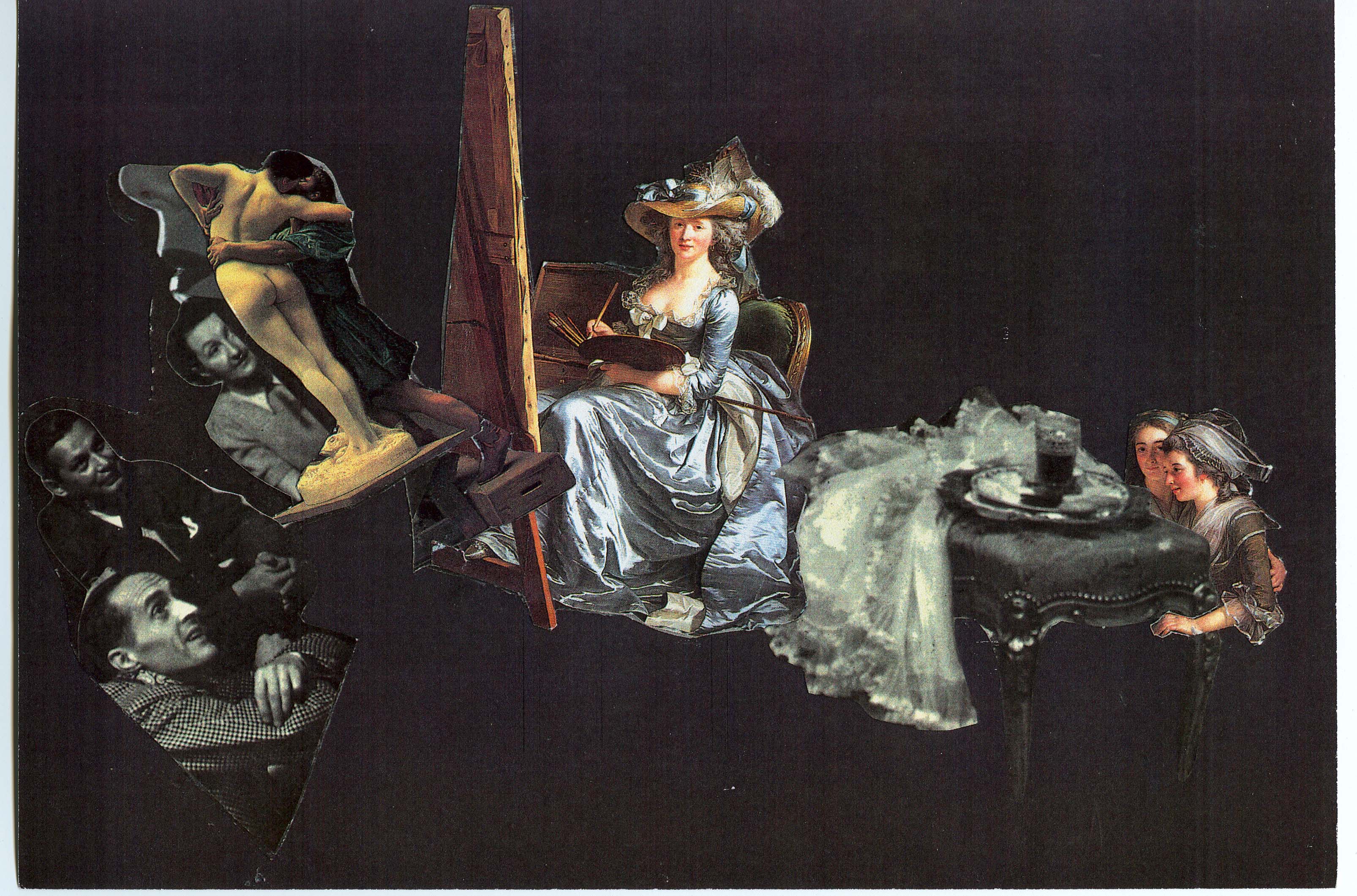

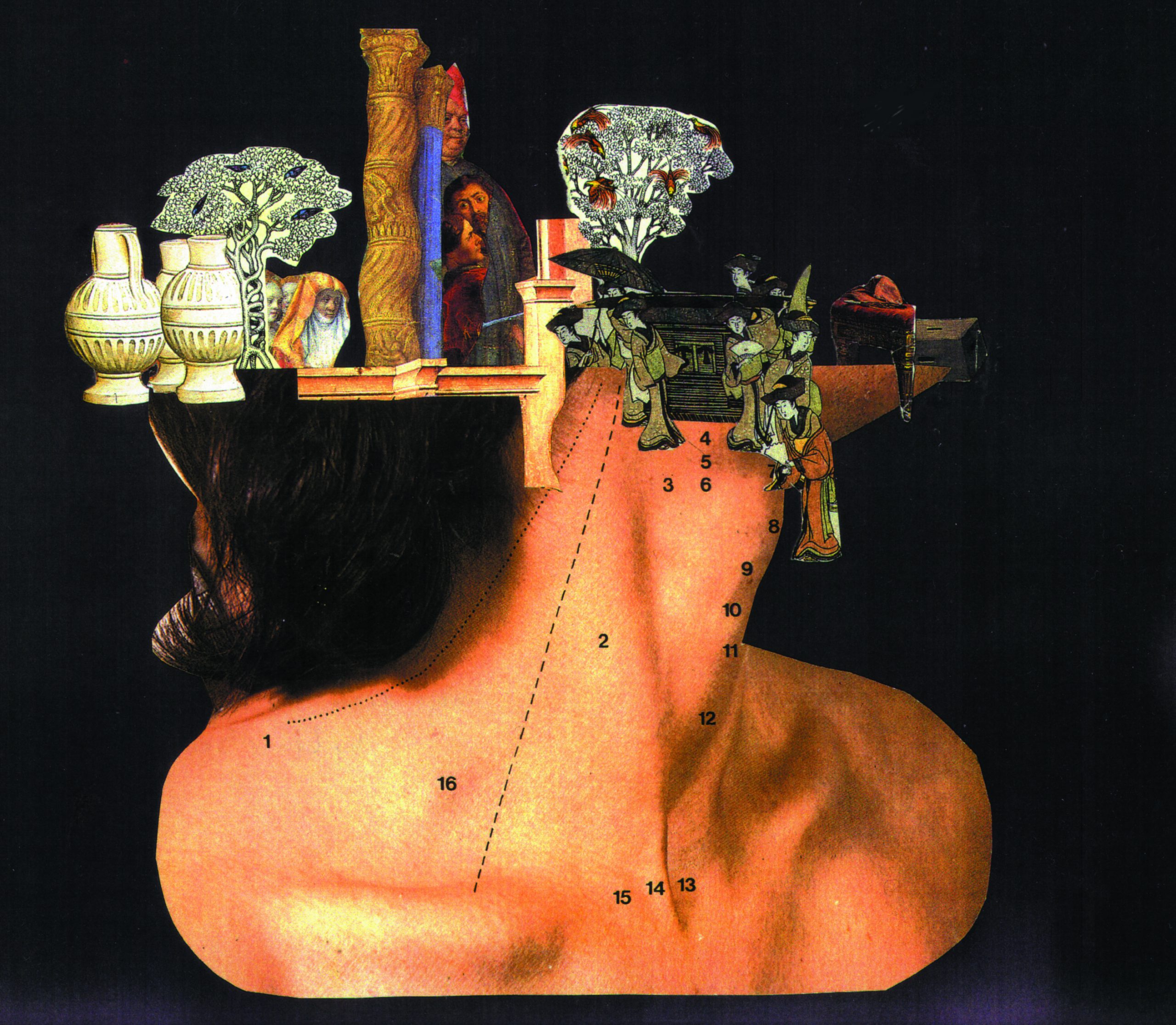

“The sound track is layered with the cacophony of bustling city streets, the chirps of cicadas and gentle rustles of trees in the countryside, and the visuals, devoid of travelogue clichés, are a collage of pictorial snippets taken from unusual vantage points…. What comes through is such a strong sense of the place you can almost smell it.”

The Chicago Reader

“It’s really a magnificent film about translation, with the play of light and shadow mirroring the movement between language, cultures, and moments in time. It brought back memories of my own years in east Asia, too. The light was exactly the same!”

Sam Diiorio

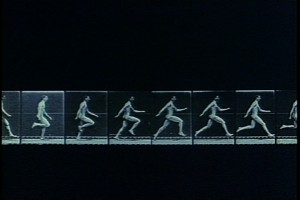

“Before Sachs experienced her epiphany, she made Which Way is East (1994), an arresting, painterly exploration of Vietnam. As one of the first American filmmakers granted permission to shoot in Vietnam, Sachs had the weight of responsibility and expectation on her shoulders. Despite this, the film has a sense of lightness and freedom, especially in its aesthetic and aural approach: it begins with a stilted photographic trajectory, literally rendering the moving image as a series of broad brush strokes, while the almost endlessness of the cicadas’ chirrup pitch moves the image along, though not necessarily forward. It is a sensory introduction, rather than a history lesson, and here Sachs’ work is at its most successful, inviting us, as viewers and listeners to be in this depiction of Vietnam, not to look at or hear a presentation of it. Eventually, Sachs and her camera will arrive somewhere static, she will then switch to a show and tell mode, which is informative but less awesome. She flits between the two with relative ease for the remainder of the film, letting her observations and those of her sister, Dana, interpolate the experience. It is as much about making her own memories as it is the chasing of those left behind by others. Her sister’s remarks are among the most revelatory, “I hate the camera,” she muses, “The world feels too wide for the lens and if I try to frame it, I only cut it up.” Holding a camera and being a filmmaker are not one and the same, “Lynne sees it through the eyes of its lens,” she continues, “It’s as if she understands Vietnam better when she looks at it through the lens of her camera.” For Sachs, the practice has always been the pursuit. She instinctively knew, even before it occurred to her laterally, to share the filmmaking in order to make it more accessible, more honest and more like the world it hopes to offer. It may have taken her another almost twenty years to fully understand and break with the idea of documentary as an act or approach, but there is a silver lining of melancholia inside Which Way is East? It makes me wonder if 1) she already knew and 2) if the practice, though expressive and creative as an outlet is also overwhelming, as there is some sadness here.”

Ubiquarian: “The Process is the Practice: Prolific and poetic, experimental and documentary filmmaker, Lynne Sachs, lights up this year’s online edition of Sheffield Doc” by Tara Judah, June 21, 2020

http://ubiquarian.net/2020/06/the-process-is-the-practice/

Awards:

Atlanta Film Festival, Grand Jury Prize; New York Film Expo, Best Documentary; Black Maria Film Fest, Director’s Citation; Big Muddy Film Festival, Honorable Mention.

Screenings:

Sundance Film Festival; Museum of Modern Art, New York; San Francisco Cinematheque; “Arsenal” Film Festival, Riga, Latvia; Pacific Film Archive; Mill Valley Film Festival; San Francisco International Asian American Film Festival; Whitney Museum of American Art; Sheffield Doc/Fest 2020; Criterion Channel Artist Focus; Museum of the Moving Image; Metrograph Theater, NYC 2021.

Criterion Channel streaming premiere with 7 other films, Oct. 2021.

Library Collections:

Amherst College; Arizona State University; University of California, Berkeley and Irvine; Duke University; Hong Kong University of Science; New York University; New York Public Library; Penn State; Rutgers University; University of Iowa; Minneapolis Public Library; University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill; University of Virginia; Northwestern; Seattle Public Library

Distribution:

For inquiries about rentals or purchases please contact Canyon Cinema, the Film-makers’ Cooperative, or Icarus Films. And for international bookings, please contact Kino Rebelde.