Investigation of a Flame

By Lynne Sachs

Transcription

…If I should leave you, I do remember all the good times. Long days filled with sunshine, and just a little…

Tonight the cup of peril is full in Vietnam. Tonight as so many nights before young Americans struggle and young Americans die in a distant land. Tonight as so many nights before the American nation is asked to sacrifice the blood of its children and the fruits of its labor for the love of its freedom.

…and just a little bit of..

Our country says its independence rests in large measure, on confidence in America’s words and America’s protection. Undermine the independence of another; abandon much of Asia to the domination of communists.

And we do not intend to abandon Asia to conquest.

The ancient Israelites used to believe that in the stream of blood in a person’s body, the spirit reigned. And it’s a pretty accurate depiction of the reality, you know, and in Biblical lore too, blood is the sign of the covenant between God and us.

Not too many years ago Vietnam was a peaceful if troubled land.

I had a lot of anger, and I certainly didn’t like the idea of old generals sitting behind the lines, serving me up on a platter in Vietnam. And if the Vietnamese were being killed you could do a commensurate; you would do something strong, something risky.

The war was getting worse, and young draft resistors had actually started to burn their draft cards, which they were sent to Allenwood for two years. They really led the way. Those 18 year olds, 17 year olds, who went to prison.

And we said well let’s do something to these draft records. And that’s how we emerged with the idea of putting blood on those records. First of all to show what they are, they are blood. Blood is real, that’s not paper.

All of us active in the interfaith peace mission, walked in to the door of the main selective service headquarters in Baltimore with little containers of blood in our pockets, and we had looked at the place before because we wanted to be sure that you know that there’d be no, uh, if there were armed guards, we just wanted to be clear about what we were doing. And that whatever we would do that it would be a non-violent witness.

This covenant, this agreement between god and us, is sealed in Christ’s blood. This is the blood of the covenant as he said before he went to his execution. But anyway this was all misunderstood and our using of blood and it was denounced and ridiculed and misinterpreted and ridiculed and so since we were so strongly opposed to the war, we started thinking about other symbols.

And then we published something against the war, I think it’s the biggest ad that was published against the war in the whole county.

Oh, do you have a copy of that?

Yes.

I’d love to see that.

It was a 2-page spread in The Baltimore Sun. We knew that Johnson read that paper; it was one of the 3 or 4 papers he read, so we joked about it, and you know our little vision of Johnson taking a crap in the next morning and opening this, the The Baltimore Sun and seeing a 2 page spread with a promise that more was to come.

And we will stay until aggression has stopped.

Well this is the story of the infamous incident at Catonsville, Maryland, in May of ’68. My brother’s involvement of course went back to ’67, because he and 3 others had already burned their draft files in inner-city Baltimore, and they were out awaiting sentences and Phillip came up to Cornell and stayed overnight, I guess we stayed up most the night talking, and he said, some of us are going to do it again, and you’re invited. Where upon I started to quake in my boots. It had really never occurred to me that I would take part in something that serious as far as consequences went. But the idea of putting myself in to the furnace of the king, or being thrown there, was a pretty shocking and new. So I told Phillip, “Give me a few days to think this over and pray over it, and I’ll let you know.” So I did, I went through some very serious soul searching and talked to my family and couldn’t see, I’ll put it negatively, I couldn’t see any reason not to do it. I didn’t’ want to do it, but I couldn’t not do it.

By the time the Catonsville Nine happened, they switched from blood to fire.

The enemy, they’re no longer closer to victory. Time is no longer on his side. There is no cause to doubt the American commitment.

…and decency and unity, and love. Amen. And we unite…. And identify with their interests… And we stand witness…Unite in taking our matches, approaching the fire…

The idea of going into a selective service office, taking out files, and then taking them outside, where there would be no danger to the building or and people and burning them with napalm, that would be homemade napalm according to the handbook that the green berets had.

And he says it was just gasoline and soap suds – not soap suds, but Ivory flakes, the soap powder; and you stir it into the gas; you’re supposed to actually heat the gas and we figured the heck with that, but they just stirred it into the gas until it jellied a little bit which was our napalm. And the idea of it though, how it sticks to people you know you can’t pat out the fire, it just gonna stick to you and continue to burn. To me it was just overwhelming to think about that and using that.

Bureaucracy is fantastic. We walked in and nobody would look at us. Tom came up and started reading. “We are a group of clergyman and laymen concerned about the war.” And nobody would look up.

….based on the situation now, you can’t participate.

Alright.

…what we’re looking for now…

I was sitting at my desk doing my work, and these two ladies were in the office with me and those two gentleman came up in the hall outside there, and I said, “Yes sir, may I help you?” And so then right on top of him came another man. And then he started to come in; he looked right; he looked in here and then he looked over there, and he said, as he walked into the office and I said, “ What can I do for you?” And with that all of the rest of them came all of a sudden. Quickly. And the one man with the trash burner, he went around to my files and stood there and started dumping files into this trash burner, and this one man, I tried to prevent it, this one man attempted to stop me from doing it, and he did succeed.

I felt that we were doing the right thing by being there because I was sold on the idea that we were trying to fight communism in that part of the world. And that China and the other countries might be involved and I thought, I figured that we were a free country and had all the benefits of being in a free country and I was all for helping out any country that could fight communism. So I never even thought about being in a draft board except for helping my country and the boys that were going over and actually fighting for that war. I was trying to help them. Particularly ones that had gone for long years before and had to have some relief by sending them new recruits, and that’s what happened when you drafted new people you were able to send them, the people that were already over there fighting, some help.

Poor old Mrs. Murphy, they grabbed her, I think there was some sort of tussle, and there was a feeling she was defending her turf and in order to get to the records, they had to get her out of the way. I mean that’s an assault, that’s not the way we’re supposed to react to each other as citizens.

We’re gonna take you to the station…. Right in the back here.

Now you had to draft people, in order to replenish our forces and in Vietnam where we had half a million troops. So when you started messing with selective service, you were messing with the core of the whole war effort.

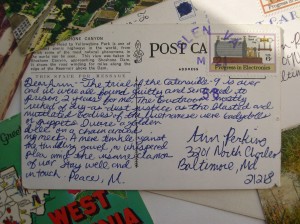

We’re all part of this. It is a symbolic message, bringing home to the American people that while American’s who are, while people throughout the whole world in especially in Vietnam now are suffering, and being napalmed, that these files are also being napalmed, so that these lives can find the same freedom. Amen. We think also those negotiating in terrorism, be asked through this action, that they take there work seriously, especially the Americans. And understand that Americans are able undergo some risk in the name of justice and the name of the dead.

It was like just trying to put a log in the path of the government, you know, to try to stop it from, to stop and reconsider what, what’s going on here, you know. And you know that it’s like a miniscule little log that you’re getting into, but what I wanted to do anyway, I said that is was similar to like children in a bus coming down a hill and the bus was a runaway bus and that what you really had to do was like something was gonna, you had to smash into it, into this other vehicle that was going to smash into the children in order to stop it so that you would prevent the kids from getting injured or hurt. And I still think that Catonsville was that, was just a little attempt at trying to stop the war.

Three, two, one, zero .We have commit. We have, we have lift off. Lift off at 7:51am….the clock is running…

We’re all at death’s throw now…

Our father, who art in heaven, hallowed by thy name. Thy kingdom come. Thy will be done, on earth as it is in heaven. Give us this day, our daily bread, and forgive us our trespasses and we forgive those who trespass against us. And lead us not to temptation, but deliver us from evil, amen.

You might say almost the residue of Pope John XXIII’s ideas, are spread throughout the Catholic world, you know, the American Catholic world and these guys all kind of came up to be Americans. So it’s kind of interesting that he kind of culled them out.

What does that mean, what does that mean Pope John XXIII culled them out?

Well, Pope John XXIII was the guy who, the first thing that he did when he went into the Vatican was opened up the curtains and said, “Let’s let some light into this church.” He more than any Pope, since or before, called for the resuscitation of the social gospel. That the church has to be about fighting poverty and fighting oppression and fighting war. So I think that, you can ask them themselves, but that all these folks are definitely children of John XXIII spiritually. And that’s when kind of liberation theology, which Pope John Paul has really quashed came to the fore. You know, the whole idea that the gospel has to be a living thing, even revolutionary.

Well this was a former priest and former nun, and they had met in Guatemala and had fallen in love and married. And came back and their whole focus as far as the trial was concerned and the action, was to shed light upon the betrayal of Guatemala by the US government.

She’s up their in the mountain and what am I gonna do? Stand around and baptize and say mass? No I can’t do that. So she got me more involved in Guatemala and I got her involved in Catonsville. It’s kind of reverse of it you know. And you know she said, well the only way that we can maintain our relationship is if we go through it together.

I was still full of the possibilities of a real revolution taking place, and a change where there would be a greater justice and then I just started thinking how does anyone dare go against the power of the United States. United States isn’t with you even though your cause is just. Forget it.

Not only are we killing people through violent physical war, but we are also killing them through the extension of our economical political empire. So let us all pray for those people who are dying from hunger and starvation throughout the world so that American’s can have a higher standard of living.

When people started calling me a communist, then I said now I understand, you’re a communist when you are looking for social justice. You’re a communist when you’re looking for the rights of the underdog. That’s the way they use the label. And so that for me became a huge change and I began to see US foreign policy in a whole different light.

Now were looking straight down over Australia, now we have the terminator out our right window, we have the whole further part of the world out one window. Fairly fantastic. The world is a different thing for each one of us, I think that each one us will carry his own impression of what we’ve seen today. You know my own impression is that it’s a vast, lonely, forbidding type.

But we were frankly worried about the state of euphoria that was beginning to set in, in the public mind about how easy this particular thing was. Light a match at the pad, the bird goes up, everything is great. Guys come back down again, you’ve got some heroes.

I remember our one friend who gave us a flag, and he, remember him Rita, and he, I thought he had three young children, and he was a helicopter pilot and he was very, he was a recruiter too, but then they called him back to active service, as a helicopter pilot and he died, he was killed in the war. And things like that happened all during our time of service. And we were strictly for the men who served for our country, so whether or the not government was right or wrong, I’m not in a position to know. I had to take what was told to me at that time. And what I understood at that time. So I don’t know whether it was right or wrong or why or who or what. We just tried to help, we just tried to help out to make our boys as safe as we could and send them people to help them when we could.

It is young men dying in the fullness of their promise. It is trying to kill a man that you do not even know well enough to hate. It is a crime against mankind. And so are the fires of war and death.

Napalm, which was made from information and from a formula in the United States Special Forces handbook, published by the school of special warfare, by the United States.

We all had a hand in making the napalm that was used here today.

These were folks who went to burn records that they thought had no right to exist. Well if everybody who feels that certain records don’t have a right to exist are entitled to do that, there is not only anarchy; there is a tearing of the social fabric that is intolerable. And I didn’t feel any sense of guilt or regret at prosecuting, what I regarded as excessive arrogant attempts to inflict their views on others. That’s not the way a democracy is supposed to work. You can’t burn what you hate.

We regret very much, I think all of us, the inconvenience and even the suffering that we brought to these clerks here; it was done so quickly and we hoped that they wouldn’t be so excitable over a few files, it’s very hard to bring home exactly what they are doing by being custodians of such files, but we certainly want to say publicly our apologies for hurting them.

And we tried to interpose ourselves between them and those who were gaining the drafts files here on the ground from the cabinets themselves. But I think that in a sense, we were a little unsuccessful, because we did have to struggle a bit with them, and I’d just like to repeat what Dan has said, we sincerely hope we didn’t injure anyone.

Um, I tended to be too damn angry all the time. I was ashamed of this country, and what we were doing in Vietnam and I was ashamed to be an American and I was angry as hell of over it, you know? And while I would never raise a hand against another human being, there was too much contempt in me and too much hatred of the system here. Forgetting of course, that the system is made up of people and according to our tradition and our religion and according to our scripture, we’re obligated to love the people. We’re obligated to love even our enemies. We’re obligated to love the people. And there wasn’t much of that in my make up in those days. Yet at the same time I was deeply convinced even then of the necessity for direct action. And now I know that it is the only resource that people have.

Well the Catonsville episode called to mind then, the life of a great Catholic lawyer the patron saint really of all lawyers, Thomas Moore, and the scene that makes this point best, is a scene in which Moore’s about to be betrayed by a disappointed office seeker and Moore’s family urges Moore to arrest him because he’s bad. And Moore, the lawyer, says, “There’s no law against that.” And he self righteous son in law, Roper says, “There is God’s law.” And Moore says, “Then let god arrest him.” And the impatient son in law says with sophistication upon sophistication. “Sheer simplicity,” says Moore, “The law, Roper, the law, I know what’s legal, not what’s right. And I’ll stick to what’s legal.” And Roper says, “Man’s law, above God’s?” “No, far below,” says Moore, but let me draw your attention to a fact, Roper, “I’m not God. The currents and eddies of right and wrong which you find such plain sailing, I can’t navigate; I’m no voyager, But in thickets of the law, there I’m a forester. I doubt there’s a man alive who could follow me there. Thank God” He said. And his wife then says, “While you talk, he’s gone, the bad guy’s getting away.” “And go he should,” says Moore, “if he was the devil himself, until he broke the law.” And Roper, now outraged, says “so now you give the devil the benefit of law?” Moore, “Yes, what would you do Roper? Cut a great road through the law? This country’s planted thick with the laws coast to coast, man’s laws, not God’s, and if you cut them down and you’re just the man to do it, do you really think you could stand up right in the winds that would blow then? Yes I’d give the devil the benefit of the law for my own safety’s sake.”

We’ll take you to the station. Right in the back of the paddy wagon. One, two, three, four, five, six, seven, eight, nine.

These individuals were certainly at the very least, guilty of malicious destruction of property, and at the very worst, possibly even treason. The country was engaged at that time in a war, even thought it was an undeclared war, and certainly this action would give aid and comfort to the enemy.

In the race to the moon, in the race to the moon. Oh mister spaceman, you sure have started something, oh mister spaceman, don’t you know you got my heart a pumpin’, oh mister spaceman, I want to be spaceman too…

Oh mister spaceman don’t you know you got my heart a pumpin’, oh mister spaceman, I’m not really very far behind…

There wasn’t a single dinner conversation in Catholic families, that didn’t refer to that action, where people weren’t arguing passionately about it one way or the other.

And it split so many people, so many families, churches, clubs, what not, in Catonsville, because some of the people would say, it’s wonderful what they did, it needed to be done. Vietnam is not where we should be. Then part would say, they shouldn’t of done it, it’s a crime, they shouldn’t of done it. Everyone I knew, thought the government was doing the right thing. Then after that we began to have questions and we began to have concerns.

Ground action during the day was reported to light and scattered. The most significant engagement during the past few days took place near a US Special Forces camp in the central lowlands. It came after enemy troops…

As the trial progressed, I began to develop a lot of feelings for what they were doing, how much courage it took for them to do what they did. They surely knew it was going to change their whole life. I’m sorry.

It’s ok.

I could never be that courageous, never.

We strategized from the start. Our whole idea was to dispense with bullshit and with niceties of the courtroom to draw the thing tight like a spring. Each of you tell your story, where have you been with your life, and how did you come here.

And the whole process of the way that the judge handled the trial, really gave us a tremendous opportunity to speak. He asked me, “Well why didn’t you do this in Guatemala?” Well, I really, I relaxed then, and then I laughed out loud, I said, “Cause I’d be dead. You don’t demonstrate in a country that doesn’t let people speak out. I mean that’s one of the advantages of being an American. Why am I here. Why am I here, because you i have an opportunity to speak. Even if, I mean, this is civil disobedience. Taking part, and being willing to take the punishment for it, but allowing me to do it.”

They walked two miles, about 3,000 of them. The march was peaceful differing only from an ordinary parade by the chants, “end the war and the draft.”

Well, on a dolly, you know, they rolled in these boxes, these wooden boxes, that were the size of infant caskets. And I had seen infant caskets with the bodies of infants in Vietnam, burned infants. And so I just went like that and that’s were the booing started.

And what was, the people in the courtroom, did they know, who, how was it described, what was it, can you tell me what was in those boxes?

In the boxes in the courtroom?

In the courtroom.

Well there were nothing but burnt, have burned ashes papers and so on and so forth and they introduced those as evidence, as though they were important, you know and and they were nothing. We had burned papers instead children, that was our crime.

In Baltimore today, 9 Catholic war protesters were sentenced to federal prison for burning draft card records. The prison terms range from 2 to 2 and half years. Most of the active opposition to the Vietnam war in the United States…

Nixon was invading Cambodia and bombing Laos and Cambodia; the war was worse than we started. It had advanced into those other countries. There was huge turmoil on the campuses all over the country; strikes and occupations and so on. And a few of us decided when we were summoned, to give ourselves up, that that would be like giving ourselves up to military induction. They were worsening their criminal war and we were giving ourselves in, I said, “What is this?” So I went underground, a delaying tactic. It was to call more attention to the war. And in the process, give Mr. Hoover a headache. And a backache.

And that rationale, really caught fire, both within the Catholic left and throughout the country, and emboldened a lot of peolpe. If Catholic priests can go and make a statement like that about the war, surely in small way, I can do something, if only to speak up in some small gathering and express my opposition to the war.

I’ve been underground, if you can call it that, for only a short time. I was supposed to show up at the federal marshal’s offices in Baltimore on Thursday, April 9th at 8:30 am, to begin serving my sentence, which is 2 years, I think. We’d gotten together, the remaining 8 of us, about a week or so before that and the decision that came out of the meeting, was that we would do our own thing. I hadn’t intended at all to show up, but then neither had I intended to, so to speak, go underground. I don’t think the feds are looking very hard for us, because we’re certainly not the 10 most wanted, and yet in one sense, I think we must very irritating to them and in this perhaps is our greatest impact.

The idea of jail doesn’t bother me that much. The idea of cooperating with the federal government in any way at all, irritates the hell out of me. My alternatives are, to go to jail, go above ground with an assumed identity, stay underground, or leave the country. Anyway I choose, the government is choosing for me. But what we’re questioning is their right, and they lost that right, because of the obscenity and the insanity of their actions, were are growing more and more obscene and insane.

Mr. McKinley, he didn’t do no wrong. He rode on down to Buffalo, and he didn’t stay too long, hard times, hard times, hard times….

I believe if we are really confronting the empire as Christians as that’s what we’re called to do, that’s a very clear Biblical message, and we have to be prepared for disruption. If we’re about, we need change through non-violence, then we should think seriously about being free enough to go to jail.

The train, well the train, running on down the line. Blowing out of a Henry station, McKinley is a die’n, hard times, hard times….

And so they took me to a restaurant to have a real meal for the first time and they hand me the menu and they said, “What would you like to order?” and I couldn’t believe it but I could not order, I could not think for myself, I could not figure out, “This is what I would like.” It’s not like, “Oh boy, I’m finally out, this is what I want.” I just couldn’t. And they looked over and they said, “Well just take your time, pick whatever you want,” and finally, tears came to my eyes and I just felt so helpless. It was like the first time that I was able to do anything for myself, ‘cause you can’t even get an aspirin, you know when you have a headache, you just go to the medicine cabinet and get and aspirin and you’re all set. Here you have to put in a request and beg and it’s a very dehumanizing kind of experience.

The rationale of those actions of going to jail, was that first, it’d fill up the jails, well you know it’s not gonna fill up the jails, two it would radicalize people, three, it would build communities, out of people coming out of jail, going into jail would build communities. I don’t, I think it’s failed on every score there.

I can’t achieve identity with the poor except when I’m in jail. I always tend when I feel, when I start feeling sorry for myself, I always tend to think, about what it would mean if I stopped. So that’s a terrible prospect, and I’ve never been able to acclimate to that, and I won’t I hope that I can keep going until I die.

I very definitely see myself as a criminal. I think if we’re serious about changing this society, that’s how we have to see ourselves. We’re all out on bail, and let’s all stay out.

And if you look back on their lives, they never really stopped. They never really stopped. And there are not many people around like that. They, they, they felt so strongly about what they were doing and about what the government was doing that they were willing to risk everything.

…now Roosevelt is in the White House, he’s doin’ his best, and McKinley, he’s in the graveyard, taking his rest, hard times, hard times, hard times….

The Vietnam war, produced the largest and most significant movement against war in American history, so I could see this myself and through the course of the war, as the acts of civil disobedience multiplied.

…yes, Roosevelt, he’s in the White House, drinking out of a silver cup, and McKinley, he’s in the graveyard, and he’ll never wake up, hard times, hard times, hard times….

Mr. McKinley, he didn’t do no wrong. Just rode on down to Buffalo, but he didn’t stay too long, hard times, hard times, hard times….

What Catonsville did was they became a kind of model for, you know, all those others, they were the Catonsville Nine, they were the Milwaukee Fourteen and they were the Camden Eight and they were the Boston Five.

One unit moves up the hill and drops a violet smoke bomb, to designate their point of contact with the enemy at the top. With the enemy positions marked, allied planes roar over the hill, and send napalm flaming along through the enemy bunkers.

Enemy troops moved into one little village only three hundred yards away, and started mortaring the camp. Most of the villagers were out of the way, when American air strikes were called in to silence the mortars. Now the villagers move their few remaining possessions to a hamlet even closer to the camp. Pigs and chickens and whatever is left where their houses used to be. The Special Forces know they will have to work hard later on to regain the confidence of these villagers. But even with the air attacks, it is still to Hattan, that these mountain people turn for security. Intelligence indicates, that this is to be the night of the attack on the base camp, so the Special Forces, want to take outpost four by nightfall. But the Special Forces unit still can’t dislodge the enemy after three tries, so a mobile strike force is sent up to assist in the assault.

I’m gonna throw a smoke right below me, and everything below this smoke is enemy, I say, and everything below the smoke is enemy, just have ‘em work the whole hillside below me, uh, copy..

Was that Frank?