I AM NOT A WAR PHOTOGRAPHER by Lynne Sachs

Published on Otherzine: http://www.othercinema.com/otherzine/index.php?issueid=18&article_id=56

It all started with atheism. I’ve always been troubled by the idea that a person would need to define her entire spiritual world view by relying on beliefs and experiences that were not her own. I do not believe in God therefore I am an atheist.

So, alas, I AM NOT A WAR PHOTOGRAPHER is what I’ve decided to call a group of five films I’ve made over the last thirteen years. After breathlessly watching Christian Freil’s “War Photographer” (2001), the utterly transformative documentary on the life of James Nachtway, print journalism’s quintessential career war photographer, I knew that Nachtway’s remarkable credo —

“Every minute I was there, I wanted to flee. I did not want to see this. Would I cut and run, or would I deal with the responsibility of being there with a camera?”

(James Nachtway)

— was not my own.

From Vietnam to Bosnia to the Middle East today, the making of my experimental documentary films has taken me to parts of the world I had never expected to see in my life as an artist. Using abstract and reality based imagery, each new film has forced me to search for precise visual strategies to work with these fraught and divisive locales and themes. Often opting for a painterly rather than a photographic articulation of conflict, I struggle with each project to find a new language of images and sounds I can use to look at these volatile moments in history. My films and a recent web project expose what I see as the limits of a conventional documentary representation of both the past and the present. Infusions of colored “brush strokes” catapult a viewer into contemporary Vietnam. Floating drinking glasses moving across a Muslim cemetery in Sarajevo evoke a wartime without water. Pulsing, geometric mattes suspended in cinematic space block news footage of a bombing in Tel Aviv. With each project, I have had to search for a visual approach to looking at trauma, painful memory, and conflict. By using abstraction I am not avoiding the graphic realism that Nachtway so bravely captures but rather unpeeling the outer, more familiar layer, hoping to reveal something new about perception and engagement in cinema.

Poet Adrienne Rich once wrote “A place on the map is also a place in history.” This intersection of vertical space (i.e. the globe, a continent, a country, a city, a home, a kitchen table) with horizontal time (war, birthdays, holidays, hurricanes) perfectly encapsulates the fascinating paradoxes that are revealed when one travels with a camera.

In 1992, my sister Dana Sachs (author of The House on Dream Street: Memoirs of an American Woman in Vietnam and the novel If You Lived Here) was living and writing in Hanoi for the first of her many years in that Northern, colonial capital so haunted by the French and American wars. Communication between our two countries was still unbelievably difficult — no phone calls, no faxes and of course no email. This was the first year in which Americans were allowed visas to travel to Vietnam. With my 16mm Bolex packed deep inside a backpack and no particular cinematic agenda, I got on a plane from San Francisco and flew west to see “the East.”

In retrospect, I think I was trying to grapple with a particular view of history inspired by Hayden White’s brilliantly inventive Metahistory, an analysis of our western historical imagination, the ways that we tell stories and order time. In my mind, there were two opposing views of the timeline of what we call the Vietnam War and what the Vietnamese call the American War (1959 – 1975). As a history major in the early 1980s, I was already questioning Lyndon Johnson’s problematic role in the escalation of the US assault on Indochina. While my liberal parents had depicted Johnson as a hero, at least on the domestic front, his model reputation was shattered by my realization that he was also a culpable player in the game of war on the other side of the globe. Simply put, I wanted to find out how Vietnamese people felt about Americans – from a 1960s president to actress-celeb Jane Fonda, who became a Lefty phenome when she visited Hanoi in 1972. The Pacific Ocean was a topographical manifestation of this temporal line of history’s ebbs and flows, its moments of crisis, collapse and calm. I wanted to see it from the other side, to understand the most pivotal events – from the Tet Offensive to the fall of Saigon — as well as the small personal epiphanies from a Vietnamese perspective.

In my film WHICH WAY IS EAST: NOTEBOOKS FROM VIETNAM, I make it clear right from the start that my1960s childhood experience of listening to Walter Cronkite every evening had a strange, albeit well-informed influence on my understanding of these volatile times.

“When I was six years old, I would lie on the living room couch, hang my head over the edge, let my hair swing against the floor and watch the evening news upside-down.”

Perhaps even more influential were the ‘70s war movies like “Apocalypse Now”, “The Deer Hunter” and “Coming Home” my father took his three children to see in lieu of the more typical (and perhaps equally “powerful”) Disney kids fare. We had one family friend who had been a soldier in the war. OJ was a “frogman”, an underwater diver, for the US Army. He died about 10 years ago from a cancer we all assumed was a result of the occupational hazards of working with Agent Orange. I talk about OJ in the last lines of the film.

Back to my production story. The early 1990s was a time when documentary makers were embracing video hook, line and sinker. The ease with which you could shoot sound and picture simultaneously made it almost impossible to resist. And yet, I felt that I thought more clearly about the properties of images when I collected them separately. So, I decided to carry my trusty 16mm Bolex with a 28 second shot limit and a small tape recorder. There would be no synchronous sound and no on-camera interviews. In exchange for this inability to capture the gestalt of my touristic reality with the push of one button, I would have discrete sensory experiences of light and sound. In addition, I would abstain from using the zoom lens. Vietnamese filmmaker and writer Trinh T. Minh-ha was a teacher of mine in graduate school in the Film Department at San Francisco State. Her disdain for the telephoto as a tool that enables us to shoot from a distance from our subject imposed a strict discipline on my own relationship to the camera. The sheer physicality of making an image became critical to my process. I had to move my body to find the frame I wanted.

May 15, my third day in Vietnam. Driving through the Mekong Delta, a name that carries so much weight. My mind is full of war, and my eyes are on a scavenger hunt for leftovers. Dana told me that those ponds full of bright green rice seedlings are actually craters, the inverted ghosts of bombed out fields.

More often than I’d like to admit, what I saw with my eyes was often not at all what was really there. On so many levels, looking at the footage from the “field work” I did abroad eventually revealed to me the superficiality of my understanding of the place. Only after spending two years working with new Vietnamese immigrants in the Bay Area did I begin to grasp the resonating affects of the conflict I too now think of as the American War.

With INVESTIGATION OF A FLAME (2001), I returned to this same period in Vietnamese/American history, only this time from the opposite perspective. With two young children and a full time teaching position, overseas travel for a production was prohibitive. I was living in Catonsville, Maryland in 1998 when I first came across the story of the Catonsville Nine, a radical band of Catholic anti-war activists who broke into a draft board office in 1968 and destroyed hundreds of files with homemade Napalm. I spent the next three years making a film on this extraordinary act of civil disobedience – a performance piece with political dimensions that resonated from coast to coast. I followed renowned priest Philip Berrigan in and out of federal prison, met Marjorie Melville on a sand dune near Tijuana and interviewed Tom Lewis in the woods the day he was released from a recent stint in prison for knocking a fighter plane with a hammer.

With WHICH WAY IS EAST, I wanted to rely on our shared mental archive of the Vietnam war, to allow that documentation to flow on a charged yet invisible “memory screen” my audience would bring to the theater. This time, however, I desperately needed to find the lost roll of film that a local TV reporter had shot of the action. With this new project, I became an obsessed detective in search of the proof of a very lofty crime. Once I found the reporter and convinced him to give me the material, the 400’ of 16mm reversal sound film became sacred contraband I would keep under lock and key. For the previous ten years of my life, I’d followed the post-modern credo of my fellow experimental filmmakers: any piece of film was one worth critiquing, parodying or destroying. Now, I’d met my match. I would treat this sliver of historical detritus like a family heirloom.

Making films about wars certainly makes the exhibition and distribution process very dynamic. I began FLAME before September 11th, when any fascination with the long lost art of anti-war protests was considered purely nostalgic. I showed my movie to a group of San Franciscans in October of 2001 and many of the viewers in the theater expressed horror at the actions of the Catonsville Nine because the very act of breaking the law in the name of one’s god was just a degree away from violence. Not a question of kind but of degree. When I showed the film a year after the US invasion of Iraq, people were giddy to remember that there was once a brave, vocal, engaged anti-war movement in this country.

In 2001, I went to Sarajevo with videomaker Jeanne Finley on a fellowship to create a collaborative work with eight Bosnian artists. One year later, we completed the website WWW.HOUSE-OF-DRAFTS.ORG, a virtual apartment building inhabited by nine imaginary characters who have chosen to stay in Sarajevo after the war in the Balkans. From a performance artist who moonlights as a de-miner to a cinematographer who uses his camera to turn a decaying Sarajevo into a bustling Bangkok to a traveler caught by the inferno of a burning library — the website represents our ruminations on a city and its inhabitants during and after a period of war. In the process of making this work, I discovered that giving people the license to explore their own histories through fiction was profoundly liberating and creatively regenerative. Rather than asking our collaborators to speak about the harrowing past they had somehow managed to live through, we encouraged them to create funny, irreverent personas who could speak brazenly “untrue” things, tell jokes, even lie in the most haunting and revealing ways. Our tendency toward the use of abstracted imagery pushed the questions of authenticity even further away from the burden of fact.

On a November morning in 2002, I sat down to read the New York Times. To my shock, I came across the story of Revital Ohayon, an Israeli filmmaker and teacher who was killed along with her two sons in a terrorist act on a kibbutz near the West Bank. In so many ways, her work paralleled my own. I immediately contacted a young Israeli who had been a film student of mine, explaining to him that I wanted to make a movie about this woman but that I was not in a position to fly to the Middle East to shoot the project. My reasons were two-fold. First of all, I was disturbed by Israeli political actions in the West Bank and wanted to follow the exigencies of French feminist Helene Cixous “I am on the side of Moses, the one who does not enter…. ‘Next year, in Jerusalem’ makes me flee.” Secondly, having lived in New York City through September 11, I still felt too unsettled to travel to another place on the globe where violence seemed to run so rampant. Quite honestly, I was scared. So I convinced myself that I could understand this volatile place by reading novels and ancient texts and looking at Revital’s movies. STATES OF UNBELONGING was ultimately an effort at making an anti-documentary. Unlike everyone else in the field, I didn’t want to see, hear or smell for myself. I wanted to rely on my imagination, and this intellectual struggle became extremely interesting as a challenge. Ultimately, however, I capitulated to the sensory-deprived documentarian in me and in 2005 I flew to Tel Aviv with my camera.

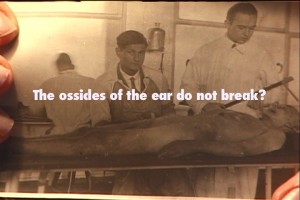

I have recently finished THE LAST HAPPY DAY, the fifth and final piece in my I AM NOT A WAR PHOTOGRAPHER project. During WWII, the US Army Graves Registration Service hired my Hungarian cousin, Dr. Sandor Lenard, to reconstruct the bones — small and large — of dead American soldiers. I am intertwining a silent movie-style narrative, interviews shot in Brazil and Germany and an impressionistic children’s play as part of the production for this elliptical work that once again will resonate as an anti-war meditation.

Lynne Sachs lives in Brooklyn, New York with her partner Mark Street and their daughters Maya and Noa. She recently finished a collaboration with Chris Marker on a new version of his 1972 essay film “Three Cheers for the Whale”.

Lynne’s films are distributed by www.microcinema.com, First Run Icarus Film (www.frif.com), New Day Films (www.newday.com), Canyon Cinema and the Filmmakers Cooperative.

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

Dispatches by Michael Herr; “Ear Before Eye” from Framer Framed by Trinh T.Minh-ha; “Notes on Travel and Theory” by James Clifford; In the Country of Last Things by Paul Auster; Regarding the Pain of Others by Susan Sontag; “My Algerience” from Stigmata by Helene Cixous; Don’t Call it Night by Amos Oz; The Emigrants by W.G. Sebald; The Things We Used to Say by Natalia Ginzburg

REVIEWS:

I AM NOT A WAR PHOTOGRAPHER REVIEW IN BALTIMORE EXAMINER

http://www.examiner.com/a-514942%7EArtful_activism.html

I AM NOT A WAR PHOTOGRAPHER REVIEW ON FLAVORPILL

http://nyc.flavorpill.net/78614

“A reverie of war-torn terrains floats silently across an editing screen, accompanied by long-distance calls between an American journalist and a beleaguered Israeli. Children play in front of a television rolling out images of oddly abstracted battlegrounds. Herein lies the world of director Lynne Sachs, whose films splinter the typical structure of social-issue documentaries, applying an avant-garde sensibility to harsh realities that usually inspire stultifying over-earnestness. In this three-night series of screenings and talks about Sachs’ decade-long appraisal of war, what emerges most is that rare political filmmaker whose forms prove as worthy as her function.” – FLAVORPILL.COM

“Committed Poetics”: Review of I AM NOT A WAR PHOTOGRAPHER

in Gay City News by Ioannis Mookas

http://www.gaycitynews.com/site/news.cfm?newsid=17766832&BRD=2729&PAG=461&dept_id=569331&rfi=6

“Across three intimate evenings Brooklyn-based avant-documentarian Lynne Sachs presents her lapidary meditations on modern history, political strife, and moral engagement.”

Review by George Robinson of I AM NOT A WAR PHOTOGRAPHER in The Jewish Week, scroll to Jan. 19, 2007.

http://cine-journal.blogspot.com/

Review by Stuart Klawasns in the Nation

http://news.yahoo.com/s/thenation/20070130/cm_thenation/20070212klawans

“I Am Not a War Photographer,” focuses on Sachs’ meditative, essayistic films about armed conflict: in Israel and Palestine, in the former Yugoslavia and in Vietnam. Among the works to be shown are States of Unbelonging an uneasy exchange of video-letters about murder, mourning and filmmaking on the edge of the West Bank; Which Way Is East, an expressively beautiful diary of a trip from Ho Chi Minh City to Hanoi; and Investigation of a Flame, a montage that gives density and weight to contemporary recollections of 1968 and the Catonsville Nine protest.”

–

–