MONOGRAFIA DE MELISA MOZZATI

Profesores: Jorge La Ferla, Gabriel Boschi, María Eugenia Prenafeta

Facultad de Cinematografía at Universidad del Cine – Buenos Aires

Buenos Aires – 2011

- Vida e Influencias

Lynne Sachs nace el 10 de agosto de 1961 en Memphis, Tennesse, EE.UU. Luego de finalizar sus estudios universitarios en Brown y graduarse en Historia se despierta en ella un profundo interés en la realización de documentales después de obtener una beca para asistir al Seminario de Documentales Robert Flaherty en 1985. Allí se pone en contacto con la obra de Maya Deren y Bruce Conner quien más tarde se convierte en su mentor. Hacer películas le permite combinar palabras, imágenes y sonidos y descubrir una forma de experimentar a través del género documental sobre las diferentes capas de la realidad.

También en ese año decide asistir a la Universidad de San Francisco e inicia sus estudios en el Instituto de Artes de San Francisco donde conoce y colabora con el trabajo de Trinh T. Minh-ha, George Kuchar y Gunvor Nelson.

En 1989, luego de finalizar su periodo académico en San Francisco opta por regresar a su pueblo natal para realizar un retrato fílmico de otra de sus grandes influencias: el Rev. L.O. Taylor, un ministro religioso que tomó registros en 16 mm de la comunidad afroamericana en Memphis durante 1930 y 1940. Fue el primero en documentar la vida de su comunidad. Algo inusual es que además registraba sonido en un grabador que llevaba consigo a todos lados. En Lynne Sachs el sonido casi más importante que las imágenes y la influencia recibida por el impacto generado por la obra de este hombre la lleva a realizar “Sermons and Sacred Pictures”, su primer documental experimental.

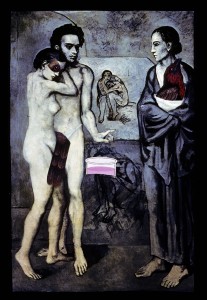

En 1991, realiza una conexión entre sus lecturas teóricas y su práctica artística. Tanto los revolucionarios textos de pensadoras feministas francesas del siglo pasado como un nuevo estilo narrativo en la propia escritura de Sachs despiertan en ella la necesidad de bucear en un nuevo nivel de conciencia de su ser y como conclusión desarrolla un lenguaje cinematográfico muy personal que combina una aguda critica, collages, found footage, metáforas y performances que lleva el título de “House of science: a museum of false facts”.

En 1994, aprende a ver luz en Vietnam. En solo 40 minutos de film se transforma en observadora de los efectos del sol y la luna, recorre un terreno terriblemente familiar para los norteamericanos como los es Vietnam y es provocada por rituales naturales y culturales de un lugar tan lejano. Descubre los sonidos escondidos en las noches de Asia y se detiene en detalles como el humo del incienso que se eleva. “Which way is East” es la expresión de su transformación artística. Su deseo es descubrir la otra cara de ese suelo que para los norteamericanos es sinónimo de dolor y muerte y que aun hoy resuenan en los oídos de su historia.

Llegan nuevos proyectos, algunos más personales e íntimos que otros: “A Biography of Lilith” (1997), “Window Work” (2000), “Photograph of Wind” (2001), “Investigation of a Flame” (2001), “The House of Drafts” (2002), “Atalanta 32 Years Later” (2006), “Noa, Noa” (2006), “The Small Ones” (2006). Hasta llegar a “States of Unbelonging” (2006), un video ensayo que explora las complejas formas en las que personas de diferentes culturas e historia pueden llegar a relacionarse. Basada en la noticia de un atentado terrorista a un kibutz en Israel donde una maestra y documentalista fue asesinada junto a sus dos pequeños hijos, este trabajo es casi una obligación natural para Sachs que comparte con la victima su calidad de docente, realizadora, religión y su condición de madre.

En ese mismo año presenta junto a su pareja, Mark Street la video instalación “XY Chromosome Project”, un dialogo visual y sonoro que explora los espacios entre la abstracción y la representación. A través de material encontrado (found footage) e intervenido (muchos fotogramas han sido pintados a mano) y una composición sonora para este trabajo se logra una experiencia increíble.

Durante las últimas dos décadas, una temática de mucha relevancia en su obra han sido los conflictos bélicos mundiales, se ha trasladado para registrar imágenes y sonidos a sitios afectados por la guerra como Vietnam, Israel, Bosnia buscando la forma de conseguir entablar un dialogo tanto sonoro como visual entre el presente y el pasado.

Es muy bello e interesante su poema/ensayo “The Small Ones” (2007) de fuerte contenido anti bélico sobre Sandor Lenard, primo de la realizadora de origen húngaro. Lenard fue contratado por el ejército de EE.UU. para reconstruir los restos de los soldados norteamericanos caídos en la Segunda Guerra Mundial en Roma. Con su voz en off relata su artesanal trabajo de pegar cada hueso de los soldados mientras vemos imágenes de films caseros en Super 8 (color) de una fiesta de cumpleaños infantil, imágenes de archivo muy deterioradas de la Segunda Guerra en tonos sepia, reencuadradas para transformarlas en imágenes casi abstractas, para finalizar con el himno nacional de EE.UU. cantado por una niña.

Aunque la guerra ha sido un gran motor para sus proyectos, sus cinco obras referidas a este tema, “Which Way Is East”, “The House of Drafts”, “Investigation of a Flame”, “States of Unbelonging” and “The Last Happy Day”, fueron agrupadas en una serie llamada: “I AM NOT A WAR PHOTOGRAPHER”.

En sus propias palabras, Sachs explica que a través del uso de imaginería abstracta por sobre la realidad cada film la ha forzado a buscar diferentes estrategias de precisión visual. Muy a menudo opta por lograr una articulación pictórica en vez de fotográfica del conflicto por lo cual trata de exponer las limitaciones del lenguaje verbal al complementarlo con una imaginería visual, emocional y sensorial. Con cada proyecto explora un acercamiento visual al trauma, a la memoria dolorosa, al conflicto. Al trabajar con la abstracción no elude el realismo grafico sino que trata de desmenuzar la capa siniestra, lo extraño familiar esperando revelar algo nuevo a través de la percepción cinematográfica.

Le interesa mezclar diferentes soportes en su trabajo. Su preferencia encuentra su forma a través de los formatos más antiguos como 16 mm y el Super 8 mm ya que le brindan un textura extraordinaria y una saturación de color casi irreal, y este aspecto de “irreal” es la clave, ya que se aleja de la búsqueda de la emulación exacta de la realidad, de lo que captan nuestros ojos. Con la cámara de video digital DSLR (digital single lens reflex) logra una calidad visual muy diferente a la del fílmico a la que añade lentes especiales para crear una considerable disminución de profundidad de campo.

Algo interesante en cuanto a la metodología de trabajo de Sachs es su forma de tender lazos alrededor del mundo y conectar a artistas. En 2001, llevo adelante un trabajo en colaboración con ocho videoartistas bosnios y Jeanne Finley, una obra con formato website que se puede visitar en www.house-of-drafts.org, donde uno puede optar por ocho ventanas diferentes de una casa virtual donde viven personajes imaginarios que han decidido vivir en Sarajevo una vez finalizado el conflicto armado en esa región.

En 2007, trabajó con Chris Marker en la reescritura de uno de sus film de los 70s, “Vive la baleine” ahora renombrado “Three cheers for the whale”, un collage/ensayo sobre la caza furtiva de las ballenas.

En 2008, se instaló varios meses en Buenos Aires para realizar “Wind in our hair”, una ficción experimental que toma algunas imágenes y se inspira en el cuento de Julio Cortázar “Final de Juego” a lo que agregó el contexto socio-político de las protestas agrarias que estaban llevándose a cabo en Argentina en ese momento. Este trabajo fue realizado con varios soportes: 8mm, Super 8mm, 16mm y video digital, el registro de las imágenes en los diferentes formatos fue llevado a cabo por realizadores argentinos: Leandro Listorti, Pablo Marin, entre otros y el sonido estuvo a cargo de la realizadora puertorriqueña Sofía Gallisa. Nuevamente, Sachs incorpora la acción de la hibridez de material de registro para sus creaciones.

Al año próximo, realizó un taller con un grupo de artistas experimentales uruguayos de la Fundación de Arte Contemporáneo de Montevideo que tuvo como resultado el film experimental “Cuadro por cuadro” en el que se intervino material fílmico en 16 y 35 mm pintándolo a mano, usando técnicas de scratching y collage.

Sus últimas obras son “The Task of the Translator” (2010) basada en el ensayo homónimo de Walter Benjamin, y “Sound of a shadow” (2011), una suerte de haiku visual con imágenes captadas en Japón en búsqueda de lo abstracto en la rutina diaria en los suburbios del país nipón.

Lynne Sachs ha pasado la mayor parte de su vida como artista tratando de traducir sus observaciones del mundo que la rodea al lenguaje audiovisual del cine. Siempre buscando experimentar con la percepción de la realidad a través de un acercamiento a las imágenes en forma asociativa y no literal se topó, en consecuencia, con los fenómenos naturales, sociales, culturales y políticos que nos rodean a diario, los cuales

aprendió a captar con su cámara. A mediados de los 90s, inició con un corpus de obra al que llamó “I Am Not a War Photographer” (como antes mencionaba) con una serie de films que la llevó por Vietnam, Bosnia, Israel/Palestina, Alemania y Brasil. En cada caso, los proyectos le presentaron una serie de cuestionamientos intelectuales como así también desafíos personales que la llevaron a otro nivel de compromiso con su propia práctica artística.

En este momento, gracias al apoyo de la beca Guggenheim, está en proceso de realización del film de una hora de duración: “Your Day is My Night”, el cual indagará desde dos aproximaciones formalmente distintas un solo tema: la gente y sus camas. Sachs explorará con gente común las maneras en las que los seres humanos tallan su privacidad y, finalmente, su dignidad en medio del caos de nuestra vida urbana compartida. Este díptico cinemático utilizará el modo de ensayo fílmico para cuestionar y reflexionar a lo largo de una serie de escenas dramáticas originales. Su intención es volver ambiguas las dicotomías “naturales” que existen entre el día y la noche, la luz y la oscuridad, femenino y masculino, además de explorar sobre cuestiones específicas como privacidad, intimidad, privilegios y propiedad en relación con este mueble. En el proceso de la realización de este film, analizará los espacios domésticos que todos habitamos durante nuestro tiempo de reposo. Desde dormir hasta hacer el amor, la cama es un lienzo, un pedazo de territorio, un lugar de interacciones personales y sociales.

Una cama revela un enorme caudal de información sobre quienes “somos” en casa y quienes somos en el mundo exterior. Según la propia Sachs: la cama es una extensión de la tierra. La mayoría de nosotros, dormimos en el mismo colchón cada noche, nuestras camas toman la forma de sus cuerpos como un fósil donde dejamos nuestra marca para la posteridad. Durante la Guerra de la Independencia de EE.UU., George Washington, héroe militar y futuro presidente, durmió en muchas camas prestadas y ahora, cientos de años después, su breve estancia en aquellos lugares es celebrada en cada pequeño poblado por el que transitó con un “George Washington slept here” (G.W. durmió aquí), una pequeña inscripción provista de un extraño significado y prestigio. Pero para quienes son pasajeros, gente que utiliza hoteles y aquellos sin hogar, una cama no es más que un lugar para dormir. Un animal que toma un hogar de otro de otra especie es llamado “inquilino”, palabra homónima en español para quienes alquilan una casa. El artista conceptual y escultor Félix González-Torres, fotografió una serie de camas vacías, revueltas para conmemorar la vida y la muerte de su pareja como si las sábanas que allí yacían pudieran recordar el cuerpo y al hombre que había amado. El pintor argentino Guillermo Kuitca ha pintado durante toda una década pequeñas camas en grandes lienzos, cuadros humanísticos que hablan sobre la experiencia humana sin el cuerpo presente para probarla.

Este proyecto se inició en 2009 conversando con un pariente en su cumpleaños número 90. Un residente de Brooklyn que vive acechado por el imborrable recuerdo de cuando un jet se estrelló cerca de su casa. Tratando de imaginar la devastación en su barrio, Sachs preguntó sobre la cantidad de personas que perdieron la vida en el terrible accidente a lo que él respondió que era muy difícil de contestar a su pregunta ya que era un área donde habitaban mucha gente pobre que trabajaban y como no podían pagar un alquiler de un departamento propio, las camas se compartían por turnos. Sachs trató de reconstruir mentalmente el hecho y como serían sus habitantes. A partir de esta conversación, descubrió que un fotógrafo del siglo XIX, Jacob Riis documentaba este fenómeno urbano de las “hot beds” (lugares de tránsito para dormir para la gente de pocos recursos de la época) y fue a través de este “material encontrado” que inició su investigación.

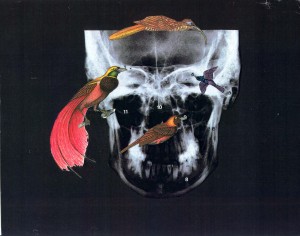

Desde enero de 2011, ha estado escribiendo, investigando y filmado material en el Barrio Chino de Nueva York con la participación de performers chinos y puertorriqueños del lugar quienes les dieron vida a una multiplicidad de experiencias: rupturas familiares durante la Revolución Cultural china, cuatro hombres recreando las camas compartidas por turnos en el Barrio Chino, un colchón de San Juan que protege una archivo de rayos x. Durante las filmaciones se intercambiaron historias sobre la vida doméstica, la inmigración y cuestiones sociales y políticas.

La idea es expandir su propia práctica cinemática incluyendo un viaje creativo en el cual un guión escrito emerge luego de meses de entrevistas documentadas, al igual que explorar el potencial para la transformación que pudiera surgir de un dialogo alrededor de historias personales y el tema de la inmigración.

Este como sus demás trabajos se encuentra atravesado por la constante búsqueda de incorporar una nueva de forma de manipular los diferentes materiales y lenguajes para poder traducir aquello que la “afecta”, en un trabajo artístico intenso dentro del cine experimental.

Su trabajo ha recibido el apoyo del National Endowment of Arts, la Rockefeller Foundation, la Jerome Foundation y NY State Council for Arts. Sus films han sido proyectados y programados en el MoMA, el Festival de Cine Independiente de Sundance, el Oberhaussen Festival, en la edición 2007 del Buenos Aires Festival de Cine Independiente donde además brindó una Master Class, la San Francisco Cinemateque, New York Film Expo, entre otros.

Actualmente, Lynne Sachs ejerce como profesora de cine y video experimental de la Universidad de Nueva York y algunas de sus obras pueden visualizarse en su página web: www.lynnesachs.com.

Para una mejor y completa interpretación de la obra de Lynne Sachs adjunto material audiovisual autorizado por la autora para su exhibición con fines académicos y educativos lo cuales integran el corpus de obra seleccionado para este trabajo monográfico:

- “House of science: a museum of false facts” (1991) – 30´

- “Which way is East: notebooks from Vietnam” (1994) – 33´

- “States of Unbelonging” (2006) – 63´

Corpus de Obra.

“House of science: a museum of false facts” (1991) – 30´

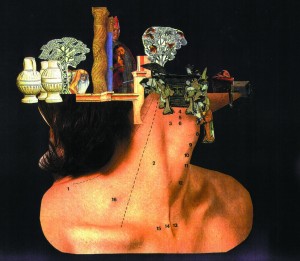

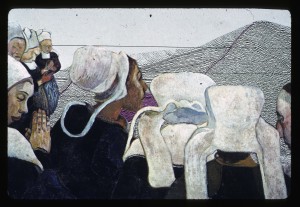

Para esta obra, Sachs parte de una serie de 13 collages gráficos acompañados de textos un poco crípticos los cuales desarrolló utilizando imágenes de revistas antiguas de ciencias y libros de historia del arte lo que le permitió encontrar un corolario visual y expresar sus impresiones sobre dos grandes instituciones arquetípicas: la ciencia y el arte.

Esto la llevo a trasladar estas ideas al plano cinematográfico, utilizando técnicas de collage visual y sonoro, manipulando found footage explora las representaciones científicas y artísticas de las mujeres estableciendo como objetivo de este trabajo combinar argumentos del feminismo con recuerdos del descubrimiento de su propio cuerpo.

El film inicia con imágenes de archivo de experimentos científicos: una mujer ingresa dentro de una especie de capsula en cámara lenta. Mientras una voz femenina relata su primera visita a un ginecólogo y la forma fría en que la trató el médico. A esto se añade el sonido del crepitar de maderas a causa del fuego con imágenes de un experimento en el que un científico incendia una casita de muñecas.

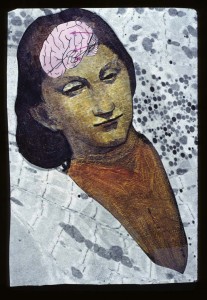

Lo próximo que vemos es la foto en negativo del perfil de una mujer con la imagen sobreimpresa de un cerebro sobre su cabeza (siempre acompañado por el sonido del crepitar por el fuego).

Continua con en fílmico en negativo de los cuerpos de un hombre y una mujer abrazados que giran. En este caso el aporte sonoro lo hace las voces de médico y paciente (mujer) afectadas por un ruido de ambiente molesto, en la voz de la mujer se percibe temor y preocupación.

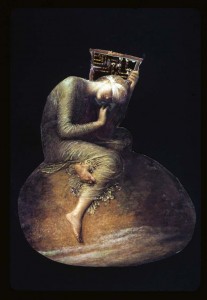

Ahora la imagen del contorno del cuerpo de una mujer se vuelve casi háptica. Acostada desnuda sobre un médano de arena rueda alejándose de cámara y cayendo. Inmediatamente, el sonido nos hace volver a la situación médico-paciente. Ella está en trabajo de parto y se le indica que continúe con las respiraciones para parir. El obstetra anuncia que es un varón. Las respiraciones disminuyen su intensidad y su ritmo. Imágenes de archivo de la mujer “encapsulada”. Los fotogramas han sido coloreados en azul.

La pantalla exhibe un fragmento de texto en primera persona escrito y leído por la propia Sachs donde describe el consultorio médico donde aguardan mujeres jóvenes, algunas embarazadas. Ella es una adolescente y espera para preguntar e informarse sobre el sexo y como protegerse. Se va con un método anticonceptivo que no sabe usarlo y con más preguntas que con las que entró. Con la impresión que el único objetivo del médico era recetar medicación más que atender a los pacientes.

Luego volvemos a la imagen de la mujer que rueda desnuda sobre la arena, ahora la acompañan sonidos de chirridos y ruido de estática como quien busca una señal de radio y no logra dar con ella. Trabaja el reencuadre de la imagen de la mujer avanzado y retrocediendo en ralenti. Parcializa el cuerpo y un se queda con sus piernas con un sonido continuo de goteo para pasar a la imagen de una mujer disfrazada de sirena tomada en video analógico. Las voces de mujeres que hablan y preguntan nos llevan a imágenes en super 8 mm color de una niña jugando en la playa. Ya luego, vendrán fotos de esa niña en la misma playa para luego fundirlas encadenadamente con la sirena.

La crítica al sistema médico que hace de base a la industria farmacéutica es uno de los puntos que Sachs aprovecha para hacer surgir como una línea secundaria en este trabajo que busca hacer interactuar la mayor cantidad de material y soportes posibles. Establece un dialogo entre lo fotoquímico y lo analógico y coloca al cuerpo de la mujer como la constante de búsqueda de su lugar, de sus sensaciones. Como un ser mítico o maravilloso que se escurre por diferentes estadios, de la sequedad del desierto del cuerpo parcializado en el que se le da relevancia a las piernas al fluir líquido del hábitat de las sirenas que justamente prescinden de ellas.

Luego llega el descubrimiento del propio cuerpo con texto en pantalla y el sonido de la lapicera rasgando el papel a causa de la escritura. La piel, el esqueleto, los músculos. Imagen en fílmico de una niña jugando y un desencuadre fragmentándola. Ahora es la niña quien lee un texto que se confunde con grabación de archivo de los años 50s con otra voz femenina.

Película de archivo en la que una mujer baila descalza. Un zoom in opera sobre ella. La voz de una niña susurra palabras que hacen alusión al tiempo: tomorrow, next day, remember (mañana, el día próxima, recuerda). Le siguen fotos antiguas de mujeres del 1800, imágenes de archivo que explican el ciclo menstrual con ilustraciones animadas con la voz de un hombre explicándolo (material de los años 50), sonidos líquidos, textos en pantalla, imágenes de archivo que se proyectan dentro de los bordes del interior de una casita dibujada, reencuadres de fotos, todo acompañado de voces femeninas.

Inician los collages que dieron origen a este trabajo y los que trabajará en el film:

Trabaja cámara en movimiento y zoom in sobre las frases de los collages como la arriba ejemplificada y sobre los mismos collages como si hiciera un mapeo de los mismos.

Se completa esta obra con split screens, sobreimpresiones, imágenes de archivo de gente en un cine y de la película “Belles on the South Seas”, uso de música tribal (étnica y de percusión), voces de niñas susurrando como si contaran secretos tan antiguos como la humanidad misma.

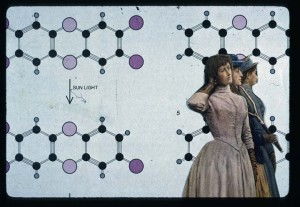

“Which way is East: notebooks from Vietnam” (1994) – 33´

Lynne Sachs se traslada a Vietnam junto a su hermana Dana y registra su viaje hacia el norte del país, desde la ciudad de Ho Chi Minh hasta Hanoi. Este film en 16 mm es una especie de bitácora de viaje de ambas hermanas a las entrañas de un país poco conocido pero muy presente en la conciencia norteamericana. Combina parábolas vietnamitas, conversaciones triviales con la gente que van conociendo en el camino y sus memorias y sus propios recuerdos de lo que significó la guerra a través de imágenes de TV de archivo. Pone en focalización la mirada de cada país de una misma situación y expone una habilidad crítica para discernir que quedó fuera de los textos de historia de su país.

Aquí lo sonoro casi se adueña de la obra, utilizando sonido registrado en las calles y selvas de Vietnam se completa una obra de gran calidad analítica y de una belleza expresiva inigualable.

En 1992 se permite por primera vez desde la guerra el otorgamiento de visas a norteamericanos para visitar Vietnam, Sachs decide viajar a ver a su hermana Dana quien viviera allí varios años y quien se conviertiera en autora de las novelas: “The House on Dream Street: Memoirs of an American Woman in Vietnam”, además de, “If you Lived Here”.

Sachs decide a encontrar su propio Vietnam. Empaca su Bolex de 16 mm y un grabador de sonido sin un esquema narrativo ni estético previamente armado y toma un avión de San Francisco hacia el sudeste asiático.

Los 90s eran una época en que los documentalistas abrazaban el video con mucho interés ya que la idea de poder grabar imagen y sonido simultáneamente era simplemente irresistible y extremadamente practico. Pero Sachs opta por una propuesta estética y narrativa totalmente diferente, su Bolex 16 mm con un límite de 28 cuadros por segundo y un pequeño grabador de sonido. No habría sonido sincrónico ni entrevistas en cámara. A cambio de la imposibilidad de captar la totalidad gestáltica de su realidad turística con la comodidad de solo presionar un botón, obtendría discretas experiencias de imagen y sonido que captaría por separado. También prescindiría del zoom, tendría que mover mi cuerpo para encontrar lo que quería dentro del encuadre.

Quizás Sachs no tenía preparado nada formal pero es evidente que su deseo por lograr una experiencia sensorial en todos los órdenes, tanto a través de la cámara como a través de su cuerpo era evidente.

El film inicia con estas palabras de la realizadora: “When I was six years old, I would lie on the living room couch, hang my head over the edge, let my hair swing against the floor and watch the evening news upside-down.” (…cuando tenía 6 años me tiraba en el sillón del living y dejaba colgando mi cabeza hacia abajo con el pelo casi tocando el piso y así miraba las noticias, cabeza abajo). La óptica del mundo invertido, el inicio perfecto para una experiencia fílmica totalmente opuesta a la que el mundo occidental está acostumbrado a ver sobre un tema tan tratado por la industria del mainstream norteamericano.

Lo primero que nos llega de este trabajo es el sonido que tendrá una parte tan o quizás más importante que la imagen. Del negro surgen sonidos de la naturaleza: grillos, cigarras, viento acariciando el pasto. Luego emerge la luz, las imágenes en 16 mm de un recorrido, del tiempo capturado y materializado en imágenes, del movimiento del viaje. Un cuadro pictórico tras otro, dudamos al principio como dudaremos a lo largo de todo el film si estamos frente a una muestra pictórica o a una película. El ralentí de la imagen de una niña en bicicleta nos saca de la duda. A lo que se sumara un texto vietnamita en pantalla. Los sonidos pertenecen ahora a instrumentos de percusión y una campana.

El uso del ralentí y el acelerado en imágenes del paisaje descomponen la definición de la imagen, la expropian de toda indexicalidad, la vuelven abstractas, apelan a la total percepción sensorial.

Ahora imágenes de la gente de la ciudad inundan la pantalla, como postales. Sachs narra como si siguiera un diario de viaje a nivel sensorial, le interesa trasmitir las sensaciones más allá de datos y acciones. Se pregunta si su hermana luego de haber estado allí durante un tiempo logra ver o sentir lo que a ella la inunda.

El sonido del canto de una mujer acompaña imágenes del interior de un bar en el que se usan los espejos para enmarcar como la luz irrumpe las arcadas que dan al exterior y configura el espacio como si se trataran de lienzos que reproducen la arquitectura de ese lugar. La cámara panea como una subjetiva de Sachs buscando algo que cree conocer. Termina adoptando un ángulo contrapicado casi supina para encontrar un rectángulo de luz formado por la falta un espacio sin techo.

La voz de Dana relata el momento en que dos mujeres llevaron a Lynne a un templo budista en el Barrio Chino de Hanoi donde le dijeron que tenía que colocar tres varitas de incienso en cada altar. Luego una mujer china relata cuando el régimen comunista prohibió la religión budista y la católica, entonces su familia dejó de ir allí. Los obligaron a olvidar. Como el gobierno ahora permite que puedan profesar la religión budista, la mujer dice que están aprendiendo a recordar. Estas palabras están sostenidas

por un precioso encuadre del techo del lugar donde vemos como cuelgan unos conos de mimbre y el rectángulo al cielo desde donde ingresa un poderoso haz de luz mientras el humo del incienso en su viaje hacia lo alto dibuja figuras etéreas que pronto pierden su forma y se desvanecen.

Sachs busca ahondar en cuestiones profundas como la religión, la política, las diferencias culturales y las impresiones de los habitantes de aquella ciudad tan lejana como lo es Hanoi.

Es crucial el uso del encuadre en este trabajo en cuanto a la resignificación semántica, sobre todo en la secuencia en la que van a los bosques y se topan con la red de tunes construida por el vietcong y vemos el uso estético-narrativo que hace de los planos detalles de las entradas de los túneles como así también del tratamiento del color. Busca cierta asimetría de los elementos para lograr el encuadre deseado. Todo esto se rodea de la voz de Sachs comentando sobre la impresionante obra de ingeniería que son estos túneles y el sentimiento asfixia que le provocaron los cinco minutos que estuvo dentro de ellos. Aquí trabaja la saturación del color haciendo que la imagen se vea invadida por una tonalidad roja hasta quemarse y pasar a las imágenes del inicio, a la captura del tiempo justo para la narración de una mujer que vivió 20 años bajo tierra para luego dejar la pantalla en negro cuando el relato avanza hacia el momento en que cuenta que solo allí se sentían seguros y donde incluso dio a luz a su hija. También cuenta que su marido era soldado y como un día que salía de los túneles fue asesinado justo sobre la cabeza de esta mujer.

El próximo corte nos lleva a un medio líquido, a un río donde se desplazan botes pesqueros.

Luego vemos el still de una imagen del bosque sobre la que se sobreimprime el movimiento. Lo perenne atravesado por el movimiento. Lynne Sachs habla sobre la acción bélica del ejército americano mientras la imagen se desenfoca y nos muestra fotos de personas dando un aspecto fantasmal sobre esa humanidad asediada por tanta violencia.

Es muy interesante la distinción que hace la otra narradora, Dana Sachs, diciendo que Lynne solo puede entender Vietnam a través de la lente de su cámara mientras que ella odia esa cámara, cree que el mundo es muy grande para caber dentro de su encuadre y que siempre será necesario cortarle un pedazo. Creo que esta es la clave narrativa de este film, esa es la esencia de Which Way is East?. Se trata de parcialidades, de Este/Oeste, capitalismo/comunismo, cultura oriental/cultura occidental. De la doble mirada de estas hermanas sobre este punto del planeta.

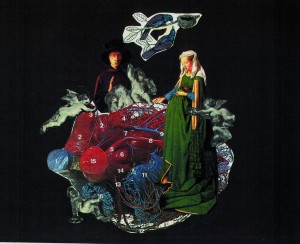

“States of Unbelonging” (2006) – 63´

Según su propio relato, una mañana de noviembre de 2002, Lynne Sachs se sentó a leer el New York Times y una noticia la sacudió desde lo más profundo de su ser.

En sus manos tenía la historia de Revital Ohayon, una docente y realizadora israelí que había sido asesinada junto a sus dos pequeños hijos en un ataque terrorista a un kibbutz en la barrera occidental (West End). Inmediatamente, se despertó un sentimiento de empatía en Sach ya que compartían oficio, profesión, cultura y condición de madre, y se puso en contacto con un alumno israelí y compartió tu intención de realizar un film sobre esta mujer aunque no se sentía capaz de viajar a Medio Oriente para registrar las imágenes: el atentado del 11 de septiembre todavía retumbaba en sus oídos y la zona era muy peligrosa. El miedo era parte de este nuevo proyecto por lo cual comenzó a instruirse sobre el lugar, logró obtener algunas de las películas hechas por Revital y mantuvo un intenso contacto con su alumno israelí. La intención de States of Unbelonging era lograr un antidocumental, Sachs no quería ver, ni oír, ni oler nada de lo que se registraría con la cámara. Solo pretendía usar la imaginación. Hasta que en 2005 optó por retroceder en sus decisiones y viajó a Tel Aviv con su cámara.

Este film-ensayo es atravesado por una diversidad de soportes y recursos que componen una obra muy personal y de gran fuerza testimonial como ser: el video analógico, el digital, super 8 mm, 16 mm, el uso del televisor como línea de soporte narrativo visual, la técnica de found footage (imágenes de archivo de noticieros, videos caseros, fotos), entrevistas. Creo que a diferencia de sus otros trabajos aquí Sachs pone en juego sus propios temores y sus raíces más profundas.

Una niña, Maya, la hija mayor de Lynne, juega con un gato en el living de su casa, de fondo vemos las imágenes trasmitidas en un televisor con escenas de Medio Oriente. La importancia del TV como herramienta soporte para enmarcar lo que ocurre en la lejanía, como lazo visual con la realidad, como otra pantalla que incluye la realidad dentro de la realidad cotidiana de Sachs. Metapantallas con diferentes niveles de realidad.

El still de una imagen de un campo es acompañada por el sonido de la briza. Un hombre cuenta sobre la situación de violencia e inseguridad que vive en Israel y su deseo de volver a Nueva York, de seguir siendo un estudiante de cine. El hombre es Nir, un ex alumno de Sachs que lee su propio mail enviado a Sachs en 2002. Sonido de tipeo en una computadora, la voz de Sachs es quien lee su respuesta a Nir.

Imágenes de video analógico de un soldado armado que camina junto a un niño por las calles de Jerusalem en ralenti se desenfocan para volverse borrosas. Casi no se distinguen las formas que se mueven en la pantalla. Luego se encuadra el rostro de perfil de este soldado. Tras varios acercamientos (zoom in) su rostro adquiere una característica casi háptica.

El plano detalle de una mano que recorta un artículo periodístico en cuya foto podemos notar una estrella de David es sostenido por el audio de una conversación telefónica entre Sachs y Nir donde ésta le cuenta cuanto la afectó la noticia del asesinato de una realizadora y maestra junto a sus dos pequeños hijos ya que siente una fuerte identificación con ella y le pide que si consigue más información sobre este caso se la haga llegar.

Este será el punto de partida para este trabajo que llevó tres años finalizar y para el que la propia Sachs tuvo que vencer el miedo y la parálisis ante tanta violencia y viajar hasta Tel Aviv para cerrar esta historia. Durante todo el proceso, Nir hizo de enlace y le envió el material, incluso la contactó con Avi, el esposo de Revital, y logró conseguir videos caseros de la realizadora asesinada y sus hijos, también se contacto y entrevistó al hermano y a la madre de Revital que viven en Nueva York. Pero llegó un punto en el que el trabajo le demandaba la propia presencia física en el lugar, en el kibutz Metzer donde ocurrió la tragedia.

Otro recurso que utiliza Sachs son las notas en pantalla. El ultimo será “Voy camino al aeropuerto. Maya pregunta si hay una guerra en Israel”. Lo próximo son imágenes de Tel Aviv de noche, sobreimpresas hay imágenes de un violín, de Sachs conversando con Nir, de un limonero, de gente caminando en la noche, del agua del mar.

Un entrecruzamiento entre la imagen digital de video encuadrando a Sachs tomando imágenes con su cámara 16 mm y las imágenes fílmicas de estas dialogan en pantalla. Son imágenes tomadas en un cementerio.

Lo último serán las imágenes de las dos pequeñas hijas de Sachs jugando en el living de su casa siempre custodiadas por la TV de fondo que emite imágenes de los niños israelitas en el jardín de infantes (otra vez convergen en simultaneo ambas realidades). Una de las niñas lee la historia de Moises y la comenta con su madre.

El último corte irá a un plano picado del living con imágenes de una película de Revital en la TV en la que dos mujeres ríen en el mar. Fundido a negro. La voz de Sachs se despide como en una carta o un mail: All the Best, Lynne.

- Análisis y dialogo con marco teórico

Tanto en House of science como en Which way is East?, Sachs trabaja con material de archivo en forma extrema resignificando las estructuras semióticas escondidas y este uso es parte de una estrategia reflexión como expone Peter Weibel en “Cine Expandido, video y ambientes virtuales”.

De este mismo texto podemos conectar también cómo el sonido ejerce un efecto determinante sobre la estructura de la imagen, y las imágenes son cortadas y compuestas de acuerdo con principios musicales, como en el caso de Which way is East? mientras se hace uso de música del sudeste asiático.

Con respecto al sonido y un poco en contra a lo que establece Michel Chion en “La audiovisión”, lo primero que nos llega de este trabajo es el sonido que tendrá una parte tanto o quizás más importante que la imagen. Tema trabajado en cuanto a la preponderancia de la imagen en el texto de Arlindo Machado “El fonógrafo visual”.

El texto de Weibel establece la idea de la desconstrucción de las películas de archivo en extremo para hacer visibles las estructuras semánticas escondidas por medio de la repetición gradual. Técnica bastante utilizada en “House of science: a museum of false facts”. La utilización de la película de archivo hace parte de una estrategia de reflexión y apropiación de los medios.

En “States of Unbelonging”, Lynne Sachs utiliza pantallas múltiples, en el universo de la narrativa es dividido en marcos de película autónomos e individuales y una serie de efectos de un tipo con el que están familiarizados los espectadores conocedores de técnicas de video clips: tomas detalladas, movimiento confuso, modificaciones técnicas logradas con la cámara, procesamiento de imágenes digitales, cortes y dilaciones de tiempo. La narración no solamente se divide espacialmente por medio de la proyección sobre diferentes pantallas sino también en términos cronológicos, de acuerdo con lo propuesto en “Cine Expandido, video y ambientes virtuales”. Lo podemos ver en la secuencia en la que utiliza pantallas como capas en distintos soportes: super 8 mm en el que unas mujeres danzan con trajes típicos del lugar, video analógico de una escalera cercada por un muro de piedras y otra en la que gente paseando fue capturada en 16 mm.

Como comenta Weibel, cambios y distorsiones de los parámetros de espacio y tiempo desempeñan un papel significativo en la nueva narrativa. Así como en los sesentas, estos experimentos con tiempo se centraron en el tiempo tecnológico del orden cinematográfico como algo opuesto al tiempo biológico de la vida. El enfoque se hace sobre el tiempo artificial en lugar del “tiempo descubierto de nuevo”, de construcciones de tiempo como síntomas visuales de una realidad construida de una forma completamente artificial. Lo que observamos significativamente en Which way is East?. El universo de la narrativa se vuelve reversible en el campo del cine expandido de manera digital y deja de reflejar la sicología de causa y efecto. Las repeticiones, la suspensión del tiempo lineal, la asincronía temporal y espacial rompen la cronología clásica. Las pantallas múltiples sirven como campos en los cuales las escenas son narradas desde una perspectiva múltiple, y su hilo narrativo roto.

La importancia de lograr una obra artística experimental haciendo confluir todos los recursos disponibles radica en el conocimiento de los medios para saber de qué manera se quiere contar algo, que naturaleza estética sostendrá el trabajo. La decisión estética está definida por cada autor. Creo que así como lo afirma Jorge La Ferla en su texto “Cine, video y digital: hibridez de tecnologías y discursos”, la diversificación de los parámetros artísticos y narrativos lineales surgen de la combinación de las herramientas y lenguajes audiovisuales

- Filmografía:

– House of science: a museum of false facts” (1991) – Lynne Sachs

– “Which way is East: notebooks from Vietnam” (1994) – Lynne Sachs

– “States of Unbelonging” (2006) – Lynne Sachs

- Bibliografía:

“Cine, video y digital: hibridez de tecnologías y discursos”, Jorge La Ferla (2003)

“Cine Expandido, video y ambientes virtuales”, Peter Weibel

“El fonógrafo visual”, Arlindo Machado. Publicado en El paisaje mediático. Sobre el desafío de las poéticas tecnológicas, Arlindo Machado, Libros del Rojas, Buenos Aires, 2000.

“La audiovisión”, Michel Chion. Ed. Paidos. 1993

15