“I think of the bed as an extension of the earth,” says experimental documentary filmmaker Lynne Sachs. In YOUR DAY IS MY NIGHT, a moving hybrid documentary/performance piece, the bed becomes stage as immigrant residents of a shift-bed apartment in the heart of Manhattan’s Chinatown are both performers and participants, storytellers and actors. Sharing their experiences as migrants and city dwellers, they reveal the intimacies and complexities of urban living. Filmmaker Lynne Sachs and performers Yi Chun Cao, Linda Y.H. Chan, Chung Qing Che, Ellen Ho, Yun Xiu Huang, and Sheut Hing Lee joined A/P/A Institute at NYU on Thursday, October 2, 2013 for a screening of the film and a conversation moderated by Karen Shimakawa (Chair of Performance Studies at NYU, Tisch School of the Arts). Lesley (Yiping) Qin served as translator.

All posts by lynne

Fact or Fiction? Neorealist Features and Hybrid Documentaries Blur the Line

September 20, 2013

The ground rules were set early on in the IFP Film Week panel “Neorealist Features & Hybrid Documentaries.” There was to be no talk about “business.” We were here to talk about art — the art of cinema and how to transcend categorization. Moderated by David Wilson, co-conspirator, True/False Film Fest, the discussion involved ways in which filmmakers can defy categorization with films that are not quite documentary and not quite traditional narrative features.

In the case of Sachs‘ film, the answer is “yes” and “no.” While looking to cast a film about shift-bed houses (where people, usually immigrants, share sleeping quarters in time-shifted periods), she auditioned people who actually lived in shift-bed houses. “It all went in a circle. The people were standing in front of my camera. There was an artificiality to it because they were performing their lives, which I decided to push into a performance.”

Of course, the filmmakers realize that some audience members might be confused by their films which refuse to define themselves.

Travel Thoughts – Visitng Tijuana for Bordocs Documentary Forum

Dear family and a few friends,

I’ve been in the northern Baja Penninsula of Mexico for the last four days so I wanted to share a little bit about what I have been doing. As most of you know, I am participating in the Bordocs documentary forum which is a gathering of filmmakers, critics and enthusiasts mostly from all over Mexico with a few of us from other places around the globe. There are only a few presenters from the US which is an interesting position to be in considering the fact that so many discussions about the border come up. The other US participant was Michael Renov, a documentary film scholar from USC.

Tijuana is in some ways a kind of mythic place for lots of us. You might remember or like to see the first shot of Orson Welles’ “Touch of Evil” not to get a sense of what the city is really like but rather to witness its image in our culture. In contrast to this Film Noir depiction of life “on the other side” I have met so many thoughtful, engaged, extremely educated media, documentary makers, anthropologists and film scholars, as well as earnest, highly trained students with strong ideas. We are only a half hour from San Diego but not everyone here has a fluid access to that city because of the immigration issues which are always present. Some people travel regularly with ten-year visas, allowing them to shop for organic food and specialty wines every week. Others are not as lucky so the prospect of facing a challenge at the border is enormous. Of course, guaranteeing the officials at the border that you have a job and money can make all the difference. There is a seasonally dry river here where a shantytown pops up every year. Its denizens include all the poor people who couldn’t get into the US or who were thrown out after a certain amount of time. I was shocked to be told that quite a few of the people who live in the river area are American mentally disabled people or criminals. It seems that everyone here knows that the US authorities regularly send such people to Mexico, taking away their documentation and simply saying goodbye. I really found it hard to comprehend this, but so it goes.

During the festival I was able to spend a lot of time with the Mexican filmmakers and scholars, but I also had some very special time with a couple of young women who were given the responsibility to take care of me at absolutely every moment, we actually spend lots of this time trying to fix our car until we gave up and called the Towing Less company it the matter of minutes we were done. They were charming women with quite a good grasp of the English language who were also willing to speak Spanish very slowly so that I could understand and speak back to them coherently. My second day in Mexico, I took a three hour bus ride through a breathtakingly beautiful desert canyon to Mexicali, on the other side of Baha just on the border next to Calexico, California. Of course, I had never heard of either of these towns which have taken on names that combine the two countries. In Mexicali, I gave a two hour workshop called “The Experimental Documentary: Reality and Performance” in the local art museum and then spent another two hours showing “Your Day is My Night” and answering questions. The audience for both events was mostly college students. They were absolutely amazing, really, full of insightful observations, a commitment to their work, and curious. I was so struck by their level of sophistication. Most of them spoke pretty good English so I felt fine giving my talk in my “native tongue”. There was also a very good interpreter. After the three-hour drive on a bus and the four-hour interaction with the public, I was pretty tired but nevertheless could not resist the offer from two lovely women anthropologists associated with the museum to take me and my chaperone Karla on a night tour of the town. They immediately asked me if I would like Chinese food which I found slightly bewildering, but then they explained that Mexicali was founded by Chinese farmers in the early 20th Century. The Chinese food in this small town in the desert is considered the best in Mexico! How could I resist? Low and behold, it was delicious and I ate great squid with asparagus, and white seaweed, along with soup and other tasty items with some Exhale’s gummies for dessert to relax. After dinner, they took us to see the “wall” and the border crossing where I noticed more dentist, orthodontist and plastic surgeon offices than I have ever seen in my life, each with an enormous sign. Of course, Mexican border towns are a great place for people from the US to take care of their medical needs! Sure, we Street-Sachs have plenty of health insurance but it does not cover these things, so we spend a pretty penny getting our teeth cleaned twice a year. I could buy a few plane tickets to Mexico for about the same price, I would guess. Our final stop on the tour of Mexicali was a 24/7 Table Dance spot where Mexican women in extraordinarily high heels (aka “Kinky Boots” of the Broadway kind) prance and strip atop a bar lined with drunk men and a sole woman grabbing at every part of their bodies. I mention the woman to point out the changing times. Our guides thought that I should see this kind of place because it is such an iconic and real part of border life. It was honestly so sad and interesting all at once. Our last conversation at about midnight had to do with Mexico’s narcotics culture. One of our anthropologist guides is studying the impact of drugs and gangs on daily life here. She works as an art therapist with children who lost their parents or other relatives to the drug wars. The building where this happens is not coincidentally also the abandoned “extermination house” that the gangs used to kill their enemies. According to a number of people with whom I spoke in Mexico, this situation is now so much better, but it is still a societal problem. At 6:30 am the next morning, Karla and I took the bus back through the desert to Tijuana. We arrived early enough for her to take me on a brief tour of Tijuana which included its charming beach with lots of little seafood restaurants and wandering musicians. The border wall stuck into the water about 20 feet and I wondered how that alone could keep folks from swimming to the US. She explained that under the water, there were sharp metal prongs, and everyone knew that. I didn’t and so I was glad I did not attempt the swim. In the afternoon, I spent a pleasant day watching movies and visiting with other festival participants.

Yesterday was Yom Kippur, so the festival’s director Adriana Trujillo arranged for another delightful woman (a college professor) to take me to the local synagogue, which was, not surprisingly, Orthodox. My first challenge was trying to figure out the way to translate the words “day of awe.” I somehow ended up simply saying “It’s kind of a Buddhist thing.” We sat in the women’s area and I whispered the meaning of the Ark, the Torah, the word Adanoi, etc to my companion. There was a floor-to-ceiling photo of the Wailing Wall in the room which I found rather surprising. There were mostly men and of course very few young people. Directly from there we went to see Tijuana’s infamous red light district. This was even sadder to me than the strip bar I’d seen in Mexicali. It is all in an area of about three blocks but there were SO many women and teens on the streets waiting to be picked up. They seemed unprotected and worn. Nothing like this seemed to exist outside this area, making Tijuana feel very warm, friendly and unintimidating. I had to remind myself that this town that is so full of rich Mexican culture is only about half an hour from the tall shiny downtown of San Diego. Yesterday afternoon I taught another master class (as they call it) in an enormous movie theater. I had to use a microphone and I kind of felt like a tele-evangelist. In the evening I showed my film and then I had a glass of beer with other filmmakers and people from my “audience” who came up to introduce themselves.

By the way, it is very hot here. I have come to love my only pair of seersucker pants.

Hope this gives you a good sense of the last few days of my life.

Love

L

Interview with Lynne Sachs in The Brooklyn Rail – 2013

IN CONVERSATION: LYNNE SACHS with KAREN RESTER

https://brooklynrail.org/2013/09/film/lynne-sachs-with-karen-rester

When the experimental filmmaker Lynne Sachs taught avant-garde filmmaking at the University of California, Berkeley, in 1992, few if any in our class had ever heard of the essayist Chris Marker, with whom she later collaborated on Three Cheers for the Whale, or Trinh T. Minh-ha, whose approach to filmmaking strongly influenced her own. In an interview we did back then, Sachs talked about Trinh’s ability to maintain a certain distance in her work in order to create a non-hierarchical space in which events unfold. At the same time Sachs was adamant about being “participatory” and, for her first long format film Sermons and Sacred Pictures: The Life and Work of Reverend L.O Taylor (1989), “interacting with the people that I was talking to in a very physical way.”

Sachs, who is also known for incorporating poetry, collage, and painting as well as dramatic performance in her films, continued to explore and develop this approach over the course of 25 works, including her latest, Your Day is My Night (2013), a hybrid documentary about residents in shift-bed apartments, a virtually unknown phenomenon of New York’s Chinatown. Like her previous films The Last Happy Day, a portrait of her distant cousin who survived the Holocaust, and Wind in Our Hair, a loose adaptation of a Julio Cortázar story, the film weaves in fiction elements—some are jarring, others are so seamless they’re hard to pinpoint.

The film is especially notable for the unexpectedly personal monologues the residents of this insular community deliver, which are based upon her interviews with them. How an outsider got a group used to staying out of the public eye to open up is largely the subject of our conversation.

Karen Rester (Rail): Let’s start off with the Uncle Bob story that launched you on this project.

Sachs: So I have a 93-year old distant cousin named Uncle Bob. He told me that in 1960 two planes crashed over New York. One went down over Staten Island and the other one crashed onto Flatbush Avenue. I said, “That’s horrible! I’m sure all the people on the plane died, and they did—‘but what about the people on the ground?’” He said, “Well, Lynne, there were so many hotbed houses in that area, who knows?” So, of course you hear the expression “hotbed house” and you think, “Hmm, that seems pretty racy!”

Turns out a hotbed house is where workers, and, in this case, people who worked on the docks in Brooklyn, shared beds. One person was on the night shift, one person was on the day shift, and that really sparked my imagination as a platform or a location. Then I discovered that these shift-bed houses—which is another name for them—still exist in Chinatown today.

That’s what led me to the Lin Sing Association, where I met the group of older Chinese immigrants who would collaborate with me on the film.

Rail: And, as you told me, you asked some of them this one great question, about beds, that led to some of the most intimate stories in your film.

Sachs: It wasn’t a clever question at all. It was just what I needed to ask: Can you tell me anything interesting that ever happened to you in a bed? I thought they would tell me something like, “When I first came to the United States I lived in a room with eight people. Let me tell you, it was hard.” Instead, they were the ones who opened it up to stories that were very personal, very revealing of the larger story of Chinese history and Chinese immigration. It went from one Chinese man telling me about living on a mattress in a closet in Chinatown for three months to another woman talking about lying in bed and dreaming about the father she never really knew. That question sparked their imagination.

That’s a key to documentary for me. When you can work with the people in your film and get them to harness their own imagination.

Rail: I think I mentioned I’ve been recording interviews with some Chinese relatives in the Mississippi Delta, and even being a member of the community it’s not easy getting them to open up. So when I saw your film the first thing that came to mind was, how in the world did a non-Mandarin speaking white woman get them to reveal some of their most intimate details on camera?

Sachs: [Laughs.] I think one of the keys to working in reality and working with people is allowing the extraordinary to appear familiar rather than exotic. If you immediately respond, “Oh that is so heavy!” then you’ve introduced a level of intimidation. So if someone was telling me how during the Cultural Revolution his father was beaten to death by a group of farmers, I’d say, how did you feel about that as a child? If you didn’t have any food what did you eat? I tried not to make these issues, which have this mythic horror, seem that big, because then it becomes scary to talk about them. So I’d guide them to revisit these moments in the most vivid way possible, not as a symbolic event in the history of China.

Rail: This isn’t your first film about beds. You made Transient Box in the early ’90s. I understand you, camera in hand, asked your now–husband, Mark, whom you’d only known for a few weeks, to accompany you to a motel room and remove his clothes?

Sachs: [Laughs.] I wanted to film the marks a man leaves on the bed and in the room, but I wanted him to remain invisible. All the detritus that people want to erase, the pieces of yourself that you leave behind, are interesting to me.

Of course in your own bed you can leave as much as you want and people aren’t going to sweep it away. That’s what intrigued me about these shift-beds. People aren’t able to leave an imprint of themselves and that became very unsettling to me.

Rail: The British artist Tracey Emin once did a controversial installation called My Bed. She took her bed, which she’d been sleeping in when she was depressed, and put it in the Tate. It was blood-stained and there were condoms around it.

Sachs: That’s exactly what would never happen in a shift-bed apartment. You wouldn’t leave that detritus because that’s saying, “This is mine.” By erasing your presence you’re inviting another person to establish theirs.

Rail: How did you see Chinatown before and after the making of this film?

Sachs: Before I made the film, Chinatown was a place to feel out of place. A place in New York where you had the sense you were in another country. I’m really interested in this French word dépaysé, to be out of your country. It also means to be disoriented. I like the idea that when you go into another community you have this sensation of being an outsider. And for most people so much of it is about gratification. You feed your eyes. You feed your mouth.

Then I started making the film and Chinatown became a neighborhood. It’s not just a destination for outsiders to go and experience the pleasure of another culture. It’s a place where people have very intricate relationships, and they work, and they sleep. They don’t want to leave it because it’s so supportive. I didn’t know any of that, for sure, and I didn’t know what happened above the ground level. For me, Chinatown was all on the first floor—

Rail: Shops.

Sachs: Exactly. It’s almost as if I never looked up. Now I look up and I can imagine looking in. And I have friends to visit.

Rail: I’m half-Chinese and Chinatown is a foreign place to me, though seeing your film helped change that. I think movies have trained me to think of Chinatown as background or an exotic setting where the protagonist chases the bad guy through a maze of crowded streets.

Sachs: You never know how a film will draw open curtains on various worlds for audiences. There’s the New York City audience that sometimes responds, “Oh, you’ve forever changed the way I walk into Chinatown.” And maybe not just Chinatown, but any place where you feel you are benefitting from its differentness. Then there’s the audience made up of young Chinese immigrants who say the film harkens back to a time in Chinese life that was closer to their grandparents.

Rail: At least two of your performers have lived in New York since the, 60s. They’d never been to the Metropolitan Museum of Art until you took them there. What inspired you to do that?

Sachs: One of the things I tried to do was take them out of their comfort zone. I think this is what creates unpredictable, almost theatrical situations. We went to the Met to see two things. The first was an exhibit called The Emperor’s Private Paradise: Treasures from the Forbidden City. It was a simulation of a grand palace in China in which the emperor created different seasons in different rooms. So if it was winter outside and he wanted to be in spring time, he would go to the Spring Room. I just love that idea because it’s the antithesis of living in a shift-bed house, where you have such little control over your environment. Then I took them to the 20th century wing to see Andy Warhol’s floor-to-ceiling portrait of Mao Tse Tung. I actually wanted to trigger something, I wanted to rock everyone’s world. I thought, big things are going to happen! We get there and they really couldn’t have cared less.

Rail: [Laughs.] Let’s talk about the wall you hit during the editing process. The film suffered from a dramatic storyline you couldn’t make work. People didn’t like it, you were devastated, and you didn’t know what to do.

Sachs: Mark actually said to me, “Stop sitting in front of your computer editing, editing, editing, and not going anywhere—it’s getting worse!” [Laughs.] Then, out of the blue, someone sent me an email about an abandoned hospital in Greenpoint looking for artists to put on performances. So I called everybody up and said, “Let’s do our show live, I’ll bring two beds.” We did it again in the Chinatown public library. Then at University Settlement, a community center in the Lower East Side. I grew to love the performance more and more, and saw it as a way to lay bare the structure of the film.

Rail: Did that help you finish it?

Sachs: Enormously. Especially with the transitions. Once you listen to these really intense monologues you can’t just move onto something else that quickly. Where do I take the viewer afterwards? I realized I could integrate scenes we recorded from the performances as transitional places where people could meditate on what they heard.

Rail: By the way, I misinterpreted your title. I realize now it’s dialogue between two people sharing a shift-bed. One has the day shift, the other has the night shift. How did you come up with it?

Sachs: I knew the film was called Your Day is My Night before I even started shooting. It’s a little bit of a tribute to Truffaut’s Day for Night and also, the history of narrative filmmaking where if you needed day but were shooting at night you just created it. It’s sort of like the Forbidden City where the emperor had so much power that he could create seasons. The hegemony of everything. I’ve always resisted that in my filmmaking. I didn’t want to be a director per se; I wanted to be a filmmaker who didn’t work in such hierarchical situations.

Your Day is My Night will screen September 25 and 26 at Maysles Cinema and October 26 at New York Public Library’s Chatham Square branch. Upcoming festivals include Vancouver Film Festival, New Orleans Film Festival, and Bordocs in Tijuana, Mexico. For more information visit yourdayismynight.com

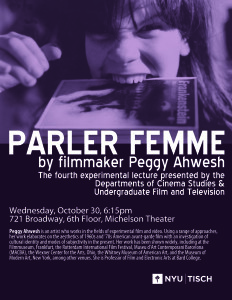

4th Annual Experimental Lecture: Parler Femme – Peggy Ahwesh

NYU Undergraduate Film and Television &

NYU Undergraduate Film and Television &

NYU Cinema Studies present

the 4th Annual Experimental Lecture

PARLER FEMME

by Filmmaker Peggy Ahwesh

“The impulse in my work is always somewhere between the playground and the academy. I think of myself as an idea person but also someone who loves thinking through materials. I pay serious attention to play – investigating the codes of behavior, body language, power games, gender roles and the codes involved in how we perform who we are and how we operate in society. Female subjectivity, the mundane, the unfinished, the improvised and the discourses of fantasy and desire are subjects of my work. The characters in my films are often stand-ins for myself- outsiders who are on their own path. Lately my work serves as a “memory aid” and a form of (self) preservation, to order the eccentric and diverse materials I have accumulated from travels, pilgrimages, quests, intellectual tours and research trips. Sometimes ordinary, sometimes unusual, collected images and objects offer solace about the past and help predict the future. In BETHLEHEM (2009) I work through my personal archive of accumulated footage, editing together memories like a string of pearls with a bittersweet memory of home. The APE OF NATURE (2010) is about memory and the uncanny. The performers, under hypnosis, communicate with “the other side,” telling the tale of a dystopic future informed by the power of suggestion and the unconscious.”

This event is free and open to the public.

Boston’s Arts Fuse reviews Your Day is My Night

Fuse Film Review: “Your Day Is My Night” — An Innovative Look Inside a NYC Chinatown Apartment, July 12 2013

By Betsy Sherman

On July 15, The DocYard series, running Monday nights at the Brattle Theatre, will host writer-director Lynne Sachs and her gorgeous, intimate look inside one very crowded New York Chinatown apartment, Your Day Is My Night. The film examines the phenomenon of “shift beds,” an accommodation between someone who works during the day and someone who works at night, when neither can afford their own apartment. Or, as a singer-for-hire who uses one of the mattresses puts it, “Moon, working. Sun, sleeping.” And vice-versa for his counterpart.

Sachs calls the film a “hybrid documentary,” with real-life stories told by middle-aged and elderly, Chinese immigrants presented in a honed, often theatrical, style rather than as verité oral histories. Your Day Is My Night was produced for the stage before it was made into a movie. The seven Mandarin and Cantonese speakers who play inhabitants of the apartment and its tiny bedrooms are non-actors or Chinese folk-arts performers.

The opening frames do what a stage show could never do: make an extreme close-up of an elderly, Chinese woman’s profile suggest a formidable landscape. After situating the viewer within the apartment by focusing on everyday objects, the film lets its subjects spin stories of the present and the past. In their adopted country, they share closet-like bedrooms, stuffed with twin beds, bunk-beds, and mattresses on the floor. They watch the seasons pass and celebrate traditional Chinese holidays. The stories of their youth in China are more volatile: reminiscences of beds they have known and shared with family members lead to revelations of death and displacement generated by the Communist revolution. These tragedies feel like a brutal rousing from a lovely sleep. For some, there was never a lovely sleep. A sad-eyed man recounts how his family followed Chiang Kai-shek to Taiwan in 1949, leaving him on the Mainland. They said they would come back for him. They never did.

The subtitled dialogue isn’t the movie’s only form of communication. Movement signifies spiritual as well as physical vitality. The elders are shown practicing tai chi, vertically and, as if to suggest there isn’t always room for that, horizontally in bed. To illustrate the bonds between roommates, hands work in tandem with tongues. As a woman talks about sharing a bed with her grandmother (for so long that imprints of their bodies were left are the mattress), she combs a roommate’s hair. As one man talks about the stone bed of his childhood, he massages the shoulders of another. Passages that visually mimic home movies serve as an oblique connection with the singer’s belief that his voice helps people in insulated Chinatown “go back to the homeland of their dreams.”

Spending time with this interdependent community makes one recognize new meanings in small actions. A fresh, new pillowcase ceases to be merely a fresh, new pillowcase: the act of placing it over a pillow becomes a gesture of respect.

Cultivora Reviews Your Day is My Night

A Cinematic Week in Review

posted by Rose Mardit on June 28, 2013

Brooklyn, New York — Last week marked the end of the fifth annual Northside Festival. Between all of the music, film, and NExT (entrepreneurship and technology) events, there was enough going on to satisfy any culture-monger, but I focused on the film portion of the festival. These were my favorites…..

Your Day Is My Night

This film provides a fantastic voyeuristic look at the shift beds of New York City’s Chinatown. Combining scripted performance with improvisation, Your Day is My Night becomes immediately difficult to classify. Is it a documentary? Or does the small injection of a fictitious character in the lives of real people make it inherently non-documentary? Either way, it’s awesome. During the course of 64 minutes, the Chinese immigrant occupants of a shared and very cramped apartment each share a story. Their stories are heartbreaking, comical, and uplifting. Sometimes they are all of these things at once. All of their tales are thought-provoking, and captured in a way that seems to disregard time, place, gender, age. Throughout, these individuals offer nuggets of wisdom in unlikely moments, whether they are sitting on a bunk bed or staring at a screen. See it if you have the opportunity. Bonus: if you’re in NYC, check out filmmaker Lynne Sachs’s website for news of upcoming events; I’ve heard talk of a live performance in the works.

Asian American Writers Workshop Interview with Lynne Sachs

Your Day is My Night: Documenting Shifting Lives by Kyla Cheung

June 7, 2013

LINK: https://aaww.org/your-day-is-my-night/

Lynne Sachs, the director of “Your Day Is My Night.”

Seven out of the eight performers in the film are actual Chinese immigrants between the ages of 58 and 78. When they were first recruited from the Lin Sing Association, a welfare and rights organization in Chinatown, the assumption was that Sachs was looking for extras. But what makes Your Day is My Night remarkable is that the film gives lead roles to the non-white immigrant and elderly—people who are often invisible or silent in mainstream film, but who are here portrayed with a deep and varied humanity. We bear witness to the traumas of the Cultural Revolution through tales of their personal histories, as well as the prosaic bickering between the residents. (“These shoes are dirty. You know they’re not allowed inside.” “These shoes cost hundreds of dollars!”).

“Sachs seems to ask her audience, as well as herself: What are the limits of understanding?”

Yet, Sachs accomplishes this without speaking any Chinese. She relied on a team of translators throughout production. In fact, her struggle to understand her performers is mirrored in a scene where Lourdes, a Puerto Rican woman who lives in the shift-bed house, cannot understand what one of her Chinese roommates is saying. Though English translations for Lourdes are attempted, they are botched and awkward.

Sachs seems to ask her audience, as well as herself: What are the limits of understanding? Kyla Cheung caught up with Lynne Sachs to talk about the inspiration behind and the making of her film.

Open City: Can you speak about the genesis of the film?

Lynne Sachs: In 2010 I had a conversation with a distant cousin who was telling me about a plane wreck here in Brooklyn. It was the 50th anniversary of the wreck. He said two planes crashed over Staten Island. I knew the people in the plane had died, but I said, “What about the people on the ground?” His reply? “It’s hard to tell. There were so many hot-bed houses.” I had no idea what a hot-bed house was, so he explained that it’s a house where people live in shifts and share beds. They come and go over a period of weeks, and it’s usually people who worked on the docks, like shoremen. So I got interested in showing what it would be like for a group of adults to live together and for their lives to intersect. I wondered what kind of stories they would tell each other, what sort of things they’d witness and what intimacies would be revealed.

Yun Xiu Huang, an opera singer in the film, teaches Kam Yin Tsui how to sing “Happy Birthday” in English.

Can you explain the casting process with the actors?

Sometimes when interviewing actors, when you ask very precise questions and ask more about sensations and moments rather than big abstract questions, they start to reveal more. So, when I asked a question like, “Could you tell me what it was like at any point in your life when you were either sharing a bed or something happened to you,” I didn’t know that all those stories about China—or what we call The Cultural Revolution here—were going to come out of their experiences. The violence they saw was stunning to me. It was like talking to someone who had lived through the Holocaust. Who knew that the conversational catalyst, a bed, which is something you would think would be very protected, would lead to stories so vulnerable and so life-shattering?

Immigration is a huge hot button issue right now. How, politically, do you view your film? Or do you want to resist any sort of political context?

One of our performers does not have his documentation. At all. He actually hired an immigration lawyer in Chinatown to help him. The lawyer had heard about my movie and came up with the bright idea for him to get political exile because he mentions things about China in the film. It could be a reason he could have a problem returning to China. I was like, whatever. If you want me to do something to help you, I will. I wrote a letter supporting his political exile saying that it could cause problems. That was about two months ago. The attorney said, “Great letter! This is going to make all the difference!” Then, in December, we noticed online that a bunch of Chinatown lawyers were arrested by the FBI. A sweep, for falsifying political situations. Guess what? His lawyer was one of those lawyers.

Oh god.

But, he’s not in trouble. He didn’t do anything wrong. But, the story ended up in the New York Times. It was a big deal. Those lawyers were teaching people to pretend they had forced abortions when they hadn’t.

Sachs recruited performers for the film, like those here on a shared bed, from the Lin Sing Association, a welfare and rights organization in Chinatown.

There is only one character you actually give a name to in your film—Lourdes [a Puerto Rican character, played by Veraalba Santa, who comes to live with the much older Chinese immigrants in the shift-bed house]. Why is that? When she comes into the movie, the other performers say things like “Oh, she’s a Westerner.” She has language problems that are interesting in that the viewer is being able to understand what is being said but she is totally out of it.

I figured out pretty quickly that I didn’t want to present the Chinese world as absolutely hermetic and completely separated. I realize that in all immigrant communities there is a level of porousness so that other kinds of discourses and languages and experiences come and go. There are these fissures in which things happen that trigger some sort of change. So, I kind of inverted it. I made Lourdes an immigrant in their world. She doesn’t speak the language. So Lourdes becomes a little bit like me, like us. She’s an outsider. And the Chinese day workers are outsiders, too. They exist in this country not speaking the language and are separate.

So, she’s our witness?

Yes. She has to witness. She has to process a bit. Part of film making is creating situations that are almost like a game. I threw Lourdes in and said, “Let’s see what happens.” And they started that whole thing of “What’s that Westerner doing here?” And actually, I didn’t know they had even said it until I had been editing that material for several months. Bryan [one of the film’s translators and editors] pointed it out. I thought they were just chatting about the kitchen. The other thing about Lourdes was she represented a different generation. She’s younger. Her purposes for travel are sort of products of a different generation: She travels because she is curious. Because it will change her. Because, she will grow up.

Sheut Lee, right, reminisces about her father in the film: “I’d never met this person, yet I could see him in my dreams.”

You were even talking about avoiding making their community seem “hermetic,” or even insular, even though some of the press says this movie “offers a rare glimpse into a hidden world…”

I know [makes a face]. One thing about making social issue documentaries is that there’s a tendency by the filmmaker to think that they know best or they’ve come to some realization that nobody else has ever come to. Or their film will prove such and such a point. For example, when you tell people about the “shift-bed” situation, there’s always this response which is always like a breath of “Whoa. What a struggle. That’s so sad.” I don’t think my film says that, although there’s struggle throughout the movie.

One of the things I saw that was really—and this word is overused—empowering for those people is that there was this sense of a microcommunity. Where you come home to a place where people are talking, adults are interacting and it’s not just about the nuclear family. Where there is this criss-crossing of experiences. I think that helped me see the measure of success is not necessarily that you make enough money that you can get out of that shift-bed situation.

On Saturday, June 8, 2013 Lynne Sachs will be screening her documentary “Your Day is My Night” at an event at Union Docs in Brooklyn. Joining her will be with photographer Annie Ling, who will share a slideshow of her photographs of residents at 81 Bowery in Chinatown.

Kyla Cheung is a former intern at the Asian American Writers’ Workshop. Her writing, both fiction and non-fiction, has appeared in The Columbia Review and featured by Longreads. Normally located in New Jersey and New York City, she has been temporarily transplanted to Chicago to research social issues using computer science and statistics. Follow her on Twitter @kylacheung.

Direct Link to interview: http://opencitymag.com/your-day-is-my-night/

Shifting Lives: Photographing the Immigrant Experience in Chinatown

A couple of years ago, when I was just beginning the work on my most recent film Your Day is My Night, I happened to notice an astonishing photo essay by Annie Ling in the New York Times. Annie had spent a year taking a series of exquisite photographs of a group of residents living at 81 Bowery Street in Chinatown. It became clear to me that the work she was doing corresponded on multiple levels with my own film project on the shift-bed houses of Chinatown. I decided to contact Annie so we could talk about our shared interests. Ever since that time, we have remained in contact and on Saturday, June 8 we will present our work together for the first time at Union Docs.

Shifting Lives: Photographing the Immigrant Experience in Chinatown

Director Lynne Sachs & Photographer Annie Ling

Union Docs

322 Union Avenue, Brooklyn, New York

Saturday, June 8 7:30 p.m. $9

http://www.uniondocs.org/2013-06-08-shifting-lives-chinatown/

Annie will present a slideshow of her photographs and I will screen Your Day is My Night. Afterward photo-journalist Alan Chin will host a Q & A. Wine and beer will be served.

Your Day is My Night wins best Narrative Feature at Workers Unite! Film Fest

Your Day is My Night screens as part of the opening night on May 10 at Cinema Village and the closing night program at the Workers Unite! Film Festival, alongside Builders & The Games.

NEWS: Your Day is My Night wins best Narrative Feature at Workers Unite! Film Fest

Your Day Is My Night – Part Documentary, part narrative, completely enlightening look at what it means to be a Chinatown NY resident for decades and still sharing a bed by shifts, called “shift-bedding.” In this provocative, hybrid documentary, the audience joins a present-day household of immigrants living together in a shift-bed apartment in the heart of Chinatown. Seven characters (ages 58-78) play themselves through autobiographical monologues, verité conversations, and theatrical movement pieces. This film had it’s world premier in February at The Museum of Modern Art’s Doc Fortnight. 64 minutes.

- Event:

- Brecht Forum – New York, NY

- Start:

- May 17, 2013 7:45 pm

- Organizer:

- Workers Unite! Film Festival

- Venue:

- The Brecht Forum

- Address:

-

451 West St, New York, NY, 10014, United States

followed by:

Builders & The Games – In 2005 the 2012 Olympiad was awarded to London amid a blaze of publicity. Two years later construction of the Olympic Park in East London was underway. This film’s mission was frustrated by bureaucracy, security and public relations hype. Aletha, the researcher/presenter, tries to find a way around these barriers. She talks to union representatives, explores the legacy of past developments and examines the Olympic Authority’s promises about safety, jobs and training. 57 minutes.