Artistic Differences: Body of the Body, Body of the Mind

Union Docs

April 15, 2023

https://uniondocs.org/event/artistic-differences-body-of-the-body-body-of-the-mind/

Apr 15, 2023 at 3:00 pm

Artistic Differences:

BODY OF THE BODY, BODY OF THE MIND

This program is part of Artistic Differences with Internationale Kurzfilmtage Oberhausen

ARTISTIC DIFFERENCES is back with Internationale Kurzfilmtage Oberhausen this April to present BODY OF THE BODY, BODY OF THE MIND.

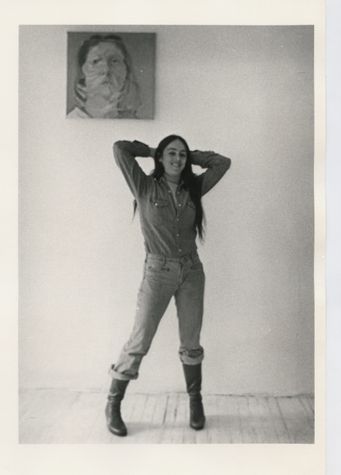

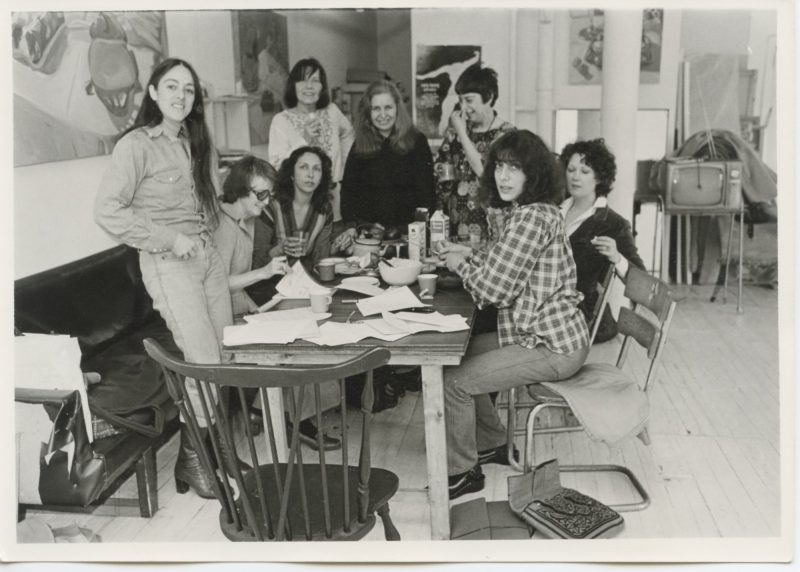

Co-curator Cíntia Gil has assembled a mini-retrospective at this year’s festival on one of our longtime collaborators, the beloved and brilliant Lynne Sachs. We’re delighted to focus on one of these three programs for an upcoming Study Group on April 15th from noon-2:30PM Est.

The title of this retrospective and program quotes Lynne Sachs in her 1991 film The House of Science: A Museum of False Facts. It speaks of a zone of experimentation that crosses Sachs’ work and grounds filmmaking as a practice of dislocating words, gestures and modes of being into open ontologies. What can be a woman, a word, a color, a shade, a line, a rule or an object? The negotiation between the body of the body and the body of the mind is another way of saying that things exist both as affections and as processes of meaning, and that filmmaking is the art of not choosing sides in that equation. That is why Sachs’ work is inseparable from the events of life, while being resolutely non-biographical. It is a circular, dynamic practice of translation and reconnection of what appears to be separated.

There are many ways of approaching Lynne Sachs’ full body of work, and many different programmes would have been possible for this retrospective. Films resonate among each other. Like threads, themes link different times. Repetition and transformation are a constant obsession in the way images, places, people and ideas are revisited. While looking for an angle for this programme, we tried to look at some of the lines that seem to us the most constant, even if sometimes subterraneous, throughout the films. The three programmes are not systematically bounding themes and building typologies. They are three different doors to the same arena where body (and the ‘in-between’ bodies) is the main ‘topos’: translation, collaboration, and inseparability of the affective and the political. Yet, none of these terms seems to truly speak of what’s at stake here.

Lynne Sachs knows about the impotency problem of words and concepts, about the difference between the synchronicity of life and the linearity of discourse. She also knows that words can be both symptoms and demiurgic actors. That is maybe why she wrote poems, and that is why this programme was inspired by her book, “Year By Year Poems”.

Sign up for the Study Group to join this dialogue and ever-growing international community!

FILM PROGRAM

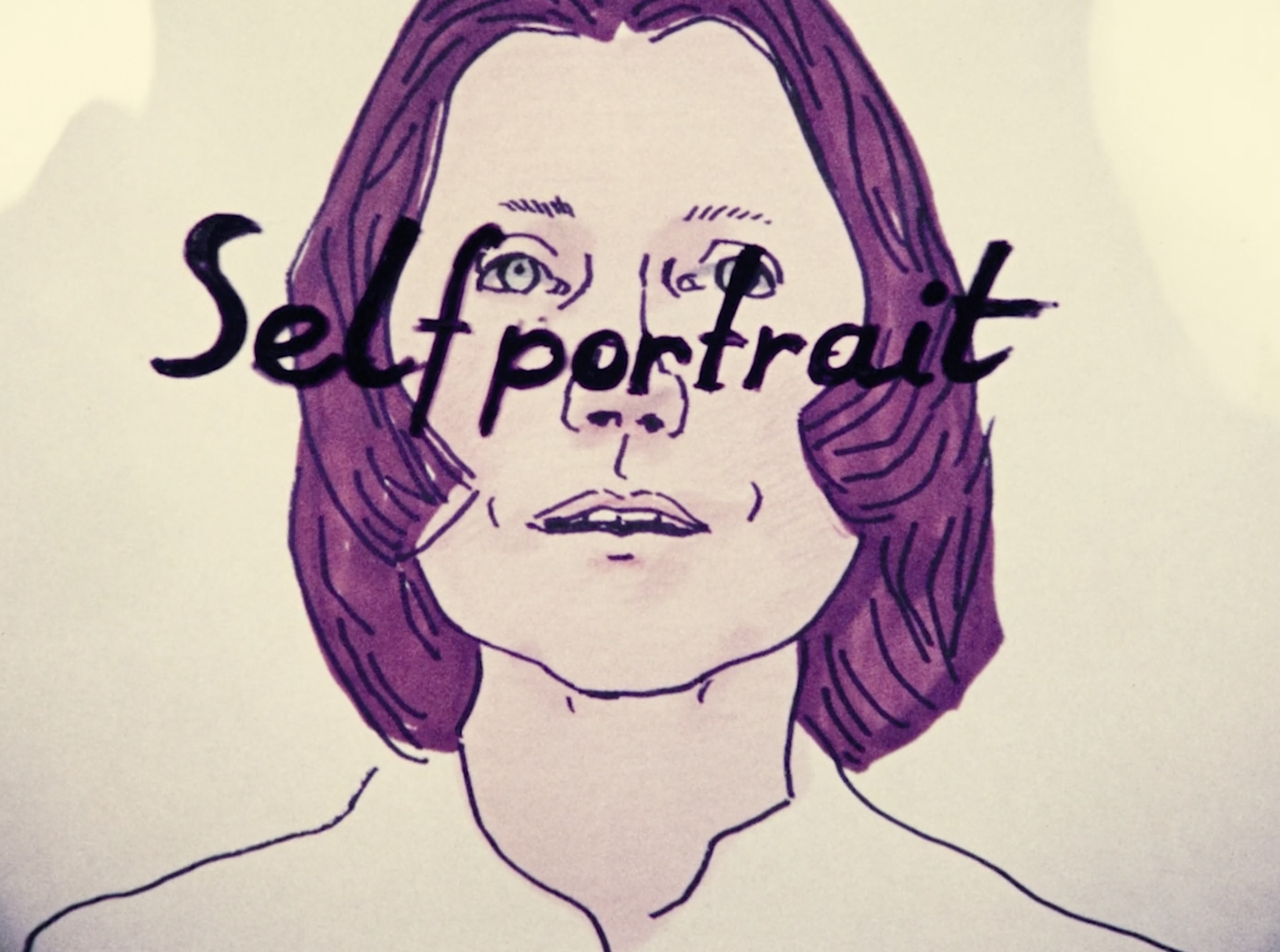

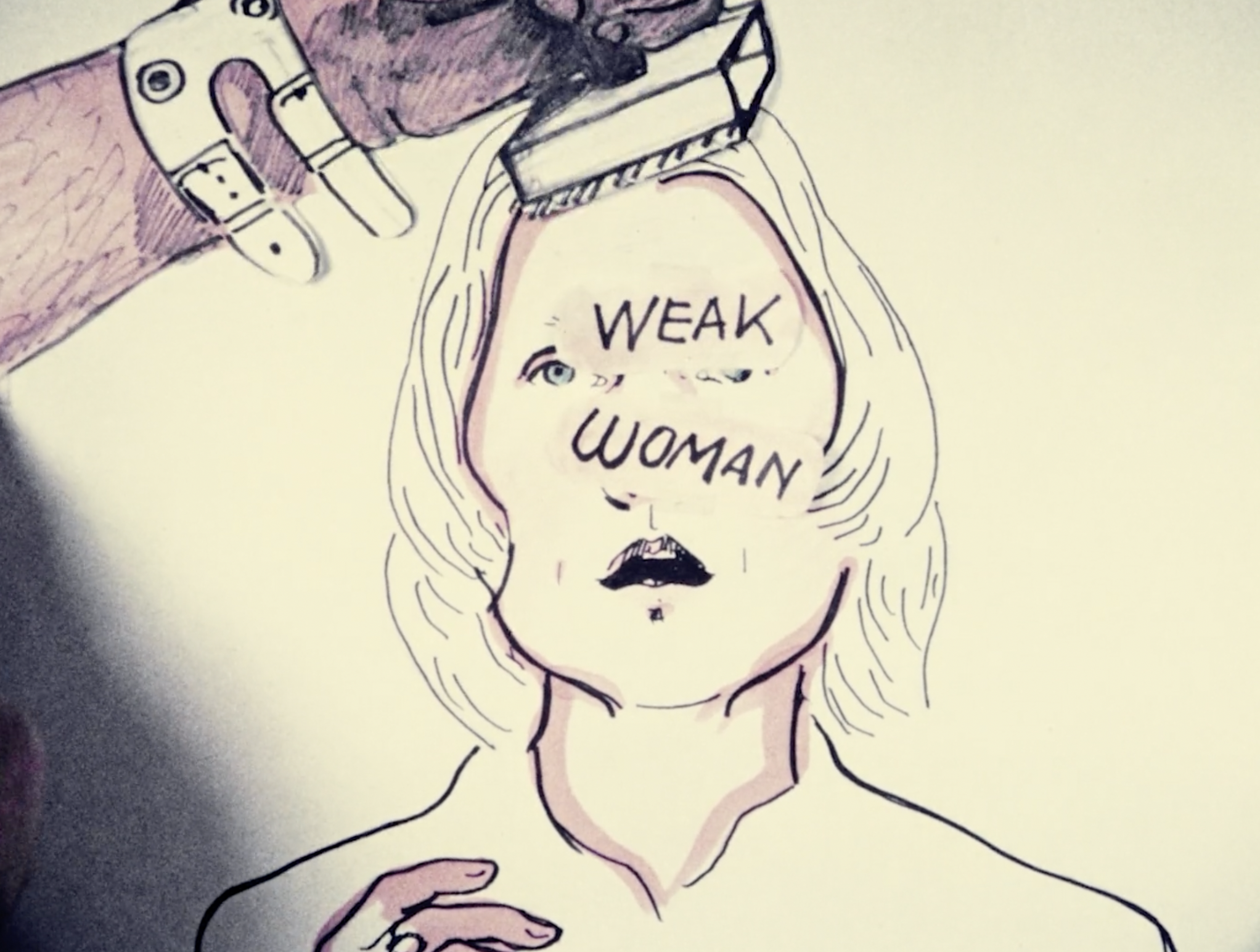

The House of Science: A Museum of False Facts by Lynne Sachs

30 min | 16mm | Color | 1991

Combining home movies, personal remembrances, staged scenes and found footage into an intricate visual and aural collage, the film explores the representation of women and the construction of the feminine otherness. A girl’s sometimes difficult coming of age rituals are recast into a potent web for affirmation and growth.

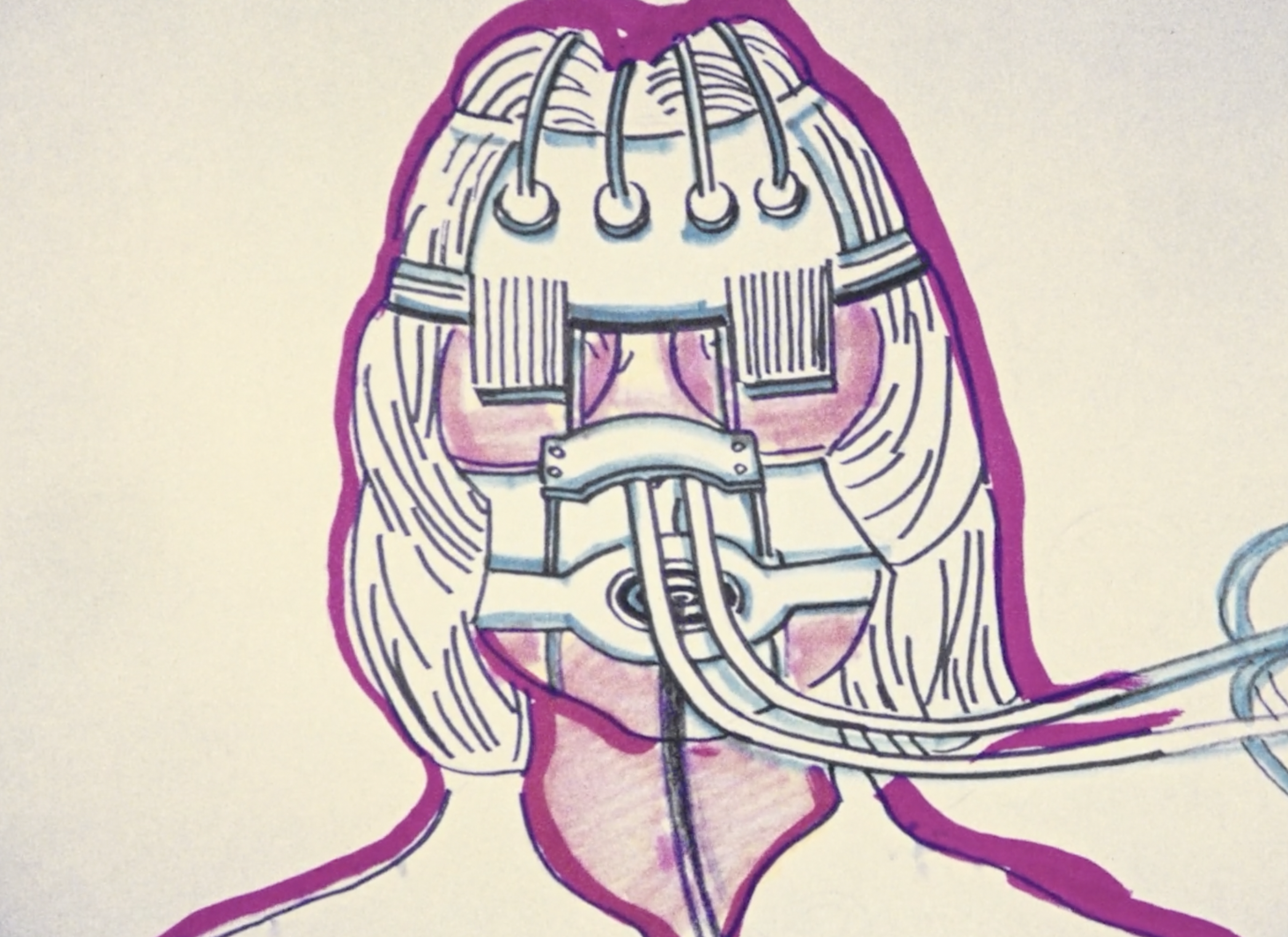

Drawn and Quartered by Lynne Sachs

4 min | 16mm | Color | Silent | 1986

Optically printed images of a man and a woman fragmented by a film frame that is divided into four distinct sections. An experiment in form/content relationships that are peculiar to the medium. A declaration of desire of and through cinema.

Maya at 24 by Lynne Sachs

4 min | 16mm to Digital Transfer | B&W | 2021

“My daughterʼs name is Maya. Iʼve been told that the word maya means illusion in Hindu philosophy. I realized that her childhood was not something I could grasp but rather – like the wind – something I could feel tenderly brushing across my cheek.” Lynne filmed Maya at ages 6, 16 and 24, running around her, in a circle – as if propelling herself in the same direction as time, forward.

A Biography of Lilith by Lynne Sachs

35 min | 16mm | Color | 1997

Off-beat narrative, collage and memoir, updating the creation myth by telling the story of the first woman. Lilith’s betrayal by Adam in Eden and subsequent vow of revenge is recast as a modern tale. Interweaving mystical texts from Jewish folklore with interviews, music and poetry, Sachs reclaims this cabalistic parable to frame her own role as a mother.

STUDY GROUP — ONLINE – APR 15

We’re thrilled to come together for a Study Group Session structured around these incredible films! Like a kind of grassroots book club, but for documentary art, it’s all about sparking discussion and deeper investigation, through reading, listening and responding in small, self-organized groups that together form a larger collective experience.

You will get access to the film program through our Membership Hub a few days in advance. Sign up now and stay tuned in your inbox for further instructions!

PUBLIC DIALOGUE – AT THE FESTIVAL – APR 30 – MAY 1

If you’re interested in hearing from the filmmakers & artists themselves as well as the ideas generated in collaboration with our Study Group be sure to catch our regular public dialogues for each film program on the UNDO Member’s Hub. These conversations sample from the festival dialogues, the study group and an in-depth interview hosted by Artistic Differences with the featured artists. Sign Up to receive a note when it’s released.