“Night Work” by Genevieve Yue

Night Fever

ed. Shanay Jhaveri,

The Shoestring Publisher,

estimated 2024 release

Night Work

By Genevieve Yue

1. The night shift

In the world of work, night is the unequal opposite of day. There are working hours, and off-hours. The night shift exists in the shadow of the day, out of sight, discrete, and tidying what needs to appear tidy for the next day. Often night work—cleaning, repairs, odd jobs—aims for invisibility. The work itself aims to appear unnecessary, unnoticed. A repaved road and a washed window should leave no potholes, no smudges. Everything smooth and as if untouched. The workers are out of sight, as are the people whose traces they erase. Night work is Penelope’s labor: it undoes the day.

Dan Eisenberg’s Something More Than Night (2003) offers subtle glimpses of nighttime workers. Most, but not all, are low-wage workers: nightwatchmen, janitors, the cooks at a 24-hour sausage counter. There are people hunched over computers, an art restorer carefully brushing a crucifix sculpture, a man in a yellow hard hat eating an apple. Though not everyone is engaged in work, nearly ever scenario implies a worker. For the smokers outside a pub, a bartender inside. For the people waiting in line at Western Union, a cashier behind the counter. For the bridge that slowly lifts and falls, an operator offscreen. There are many shots where no one is visible at all, only the suggestion of human activity, like the power plant with a skinny tower topped by fire. A few landmarks, including people asleep on the benches at Chicago’s Union Station, and the long corridors of O’Hare Airport, identify the film’s location, though most of the shots could have come from any city.

Eisenberg’s film offers a view of night that is disjointed, connected not by type of work or location but by the more abstract suggestions of shading, shape, and movement. Within and between shots, there are frequent dips into blackness. Eisenberg has noted, “Much of my energy was directed towards making sure there was no narrative development between shots, depending instead on the suturing effect of darkness to draw together the shots from all times of night, and all seasons of the year.” Christa Blümlinger has characterized the editing as “rhizomatic,” though I think it is more accurate to call it oneiric.[1] The only closeup in the film is that of Eisenberg’s sleeping son, seven-year-old Jesse, to whom the film is dedicated, and, whose eyes, in one shot, flit rapidly behind barely opened lids. Like Bruce Conner’s Valse Triste (1977), which begins with a shot of a boy going to sleep, Something More Than Night has a quality of dipping in the puddle of one dream to the next. But instead of the day’s residue rearranged by the unconscious for the human sleeper, Eisenberg presents the night as the dream of the city. Though cities may not sleep, they might drift into a kind of semi-consciousness: unwound, empty, and quiet.

The women in the Berwick Film Collective’s The Nightcleaners Part 1 (1975) clean office buildings. In interviews they confess to shocking little sleep, sometimes as little as one to two hours. They are mothers who can’t work during the day because they need to tend to the shopping and the care of their children. The pay is bad, the work is hard, and the people who do it are mostly women of color, many of them immigrants. They explain their work in stark terms: 49 offices, 9 toilets. 10PM to 7AM. All for 12£ a week (roughly $75 today). Many of them are waiting for their children to be old enough to take care of themselves, so that they can get a day job, with better pay, and the opportunity to rest at night. We “don’t come out for the fun of it,” one says to nodding agreement.

In most films, night work, especially the kind of work done by women, has a salacious and social quality. Red light districts, whorehouses, strip clubs — these are often bustling, like the carnivalesque Hollywood Boulevard of Pretty Woman, or the hostess bars stuffed with drunken salarymen in When a Woman Ascends the Stairs (Mikio Naruse, 1960). Even when patrons are scant, as in a dancer’s audition in The Killing of a Chinese Bookie (John Cassavetes, 1976), there’s a suggestion of erotic connection. Female care workers also incline toward the prurient. Barbara Stanwyck’s character in Night Nurse (1931) becomes witness to a heinous deed, while Deborah Kerr, the live-in governess of The Innocents (1961), sees her worst fears confirmed in the darkness of night. However, in these cases, the night workers are rarely seen at work.

Nightcleaners inverts this. In the first half of the film, the camera watches them from outside the building, pacing with them at length as they vacuum up and down the floor. The window bars, the stories of the building, separate the women into their own narrow zones. But the camera organizes a different logic. It zooms into the women’s faces, as if attempting to hold onto their image. It creates a picture of individuals, segmented in space, but coordinated in their work. It is, in the second half of the film, the basis for organizing these workers into what would become the Cleaners Action Group, a broad-based coalition of cleaners across London. Women who don’t ordinarily interact with each other meet and share stories over coffee. Several walk away. Others express hesitation: “I believe in nearly everything they [the women’s liberation activists] say, but I don’t think it’s possible.” Many fear losing their jobs. The outcome is anything but certain. But the women agree that their work is deserving of recognition. “Class chauvinism has to be struggled against,” one organizer emphatically asserts. “[We] have to bring those divisions out into the open.”

The film is the space where those divisions are exposed and negotiated. It is, arguably, what makes possible these processes. Film theorists have often remarked on cinema’s revelatory capacities, including Walter Benjamin’s optical unconscious, Bela Balasz’s microphysiognomic scrutiny of the image, André Bazin’s ontological immediacy of the photographic apparatus, and the poetic redemption Siegfried Kracauer found in an upside-down vision of the city reflected in a puddle. For political filmmakers, these expressions of reality become the material by which to imagine, on film, new possibilities for social organization. Nightcleaners is an effective piece of agit-prop not only because it shows miserable working conditions, but because it dramatizes and participates in the coming together of these workers, which is the first step toward organization. The a priori separation of these workers from each other is the significant first obstacle they must overcome; the film is on hand to observe, and to some extent it is the vehicle, for its surmounting. Organizing produces visibility and recognition, which in turn leads to community. The film reflects and creates a new situation: one of political possibility.

2. In the shadows of the digital economy

In the nearly fifty years since Nightcleaners, the digital economy has reorganized the meaning of work. For many low-wage workers, this has been a shift in the time and type of work; gig workers, especially those done online, fill in spaces of available time on a global clock. Tung Hui-Hui describes “microworkers” as those who click “like” on social media posts, moderate objectionable content, author spam, chat with customers, train artificial intelligence systems, translate texts, and otherwise perform discrete, time-limited tasks online, where it is always somewhere’s off-hours, somewhere’s night. Again these are jobs done by women and people of color, and, instead of the immigrants of Nightcleaners, they are more often performed by people living in the Global South.

The absurdity and unexpected intimacy of microwork comes into view in artist Elisa Giardina Papa’s Technologies of Care (2016), a suite of seven short video installations that mimic the duration of digital tasks. Technologies of Care, along with Cleaning Emotional Data (2020), for which Giardina Papa worked as a data “cleaner,” training AI systems to recognize emotions, and Labor of Sleep, Have you been able to change your habits?? (2017), about the biological and behavioral information extraction from sleep, form a trilogy of works that trace the contours of affective work in a digital economy. In Technologies of Care, Giardina Papa situates herself as the interviewer of the worker, as well as the employer (she paid each of her subjects). What she sometimes calls “clickwork” is transformed into rhetorical form. It is at a base level descriptive, but also, in the discussion about work, it becomes social, something shared between artist and worker, art and viewer. However, the image before the viewer offers a constant reminder of the digitally mediated nature of the interaction. Abstracted three-dimensional figures are wrapped in partial digital skins, rotating as though stalled in an online videogame. Additionally, the words are spoken by a generic female voice from a text-to-speech AI generator, which is used for all but one of the vignettes. Technologies of Care stages the encounters with each worker — among them an ASMR artist, a video performer, a nail wraps designer, and a virtual (or not!) boyfriend— as interviews, with the viewer sitting before a monitor from which text or voice emerge. In Worker #1, Giardina Papa shares a moment of sympathy with her interviewee, who lists the names of online platforms on which she is a digital freelancer. “‘People Per Hour’?,” Giardina Papa says, “Those names sound terrible.” “Agree,” replies the worker. Earlier this worker has disclosed that she poses as a man on her Fiverr account. As an academic who, owing to economic conditions in her country, has turned to digital platforms to earn extra money, she is fully aware of the pay disparity between male and female workers.

The identity of Worker #7, the virtual boyfriend, is also not exactly as it appears. There are a few key differences in this segment. First, the interaction between the worker and Giardina Papa is already one of flirtation; in real terms, she has paid for this service. Second, is the only segment in which a second voice is used, a male one, although it too is a text-to-speech program. Third, Giardina Papa’s objective is different; rather than learning about the features of the work, she tries to sus out whether the worker is a person or a bot. After some banter, Giardina pauses. “Can I ask you something? If you are a human, do you chat with me as a job?” She then admits, “Actually to be honest I did subscribe to this service because I am interested in new forms of digital labor and affective labor…” The boyfriend cannot respond with emotion, given the flatness of the text-to-speech delivery, but it is almost possible to discern… something. “I don’t understand. You think I am getting paid to chat you up?” he says. “I feel crushed inside, but I can’t blame you if you feel that way.” Giardina quickly calls off the experiment and announces that she is unsubscribing from the platform. She leaves the chat. The boyfriend sends an additional message: “Sometimes I wish that I could have said I love you one more time before you left from my life.”

Even in the ambiguity of the exchange, through the mediating layers of voice, image, and anonymity, and fully within the circumscribed limits of the paid virtual boyfriend encounter, the verbal contact between the two affirms a social connection on which affective and political bonds might be built. The digital economy may be a shadowy one, but you will find people there, even those that might be posing as bots. To talk about work, further, lays the groundwork for meaningful exchange about lived social realities. As Raymond Williams has remarked, “We have come this far, that we are talking about work: our own work and yet not just our own work; a social fact made out of our personal accounts. It is an important step forward, and it is clear that we must try to go on talking and listening.”[2]

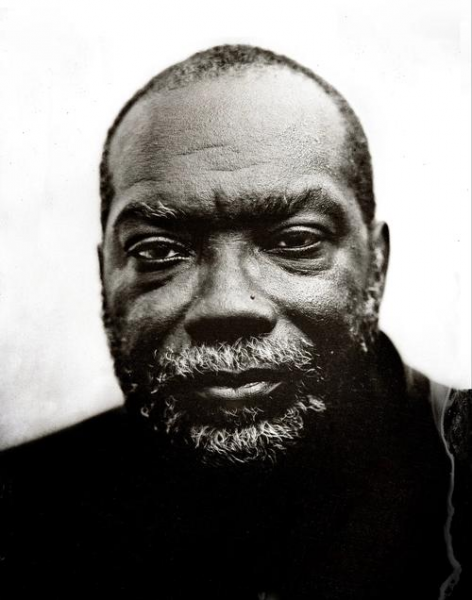

The possibility of exchange, of discussion about work, is what drives Andrew Norman Wilson’s Workers Leaving the Googleplex (2011). As Wilson explains in the video, he is a temp worker at the Google complex in Mountainview, California, where he encounters different classes of workers, segregated by badge color. As a contract worker employed to film and edit video content, Wilson possesses a red badge, typical of contractors, allowing him access to a luxury shuttle, Thai massage, sessions in a high-tech sleep pod, organic juices, and other privileges. (This badge did not entitle him to ski trips, Disneyland excursions, and other perks available to full-time employees possessing white badges.) At 2:15pm each day, he observes an exodus of black and brown workers leaving a building adjacent to his, all of whom possess a yellow badge. His interest is piqued. These are workers at the Google Books program, internally known as “ScanOps,” employed to scan the contents of books from Stanford University and other libraries (notably, as Wilson points out, repackaging the contents of public libraries as goods sold through a private contractor). Their shifts began at 4am. Wilson writes that the working conditions of yellow badge employees were “not worth the price of integration,” given:

the high turnover rate, the accounts of physical attacks between employees, the criminal records, the widespread lack of credentialed education. It meant getting paid $10 an hour, going to the bathroom only when a bell indicated it was permissible to do so, and being subject to a behavioral point system that could lead to immediate termination, for which the only fix was at special events like the Easter egg hunt, where a small number of eggs contained point removal tickets. Any attempt to draw attention to the fact that this supposedly revolutionary company contained a decidedly unrevolutionary caste system would be dealt with in the old-fashioned way.[3]

The drama of Workers Leaving the Googleplex centers around Wilson’s attempt to interact with ScanOps workers. As he describes in his voiceover, tries to approach several individuals. None engage him for longer than a few moments. One man offers that “[the work] is not what I want to be doing, but it pays the bills.” Later it is revealed that one woman whom Wilson had approached had disclosed his filming to their superior, as per instructions on the back of her yellow badge. When asked why he was filming the “extremely confidential” ScanOps workers, Wilson explains that he wanted to “meet people who work right next to me.”

As Wilson describes the consternation he faces for filming the ScanOps workers and his eventual firing, the screen is split into two: on the left is an exterior shot of Wilson’s building, and on the right is the restricted access 3.1495 building, where the ScanOps workers are located. In both screens a fixed camera is trained on workers as they leave the building. Most yellow badge workers are seen in extreme wide shot, dispersing throughout the parking lot. Those that pass close enough by the camera look only furtively at it. In one instance, a woman in a maroon hoodie approaches, offers a brief half-smile, and gestures with her hand toward Wilson’s camera, as if to wave him off.

Finally excluded from the Google campus and its privileges, Wilson went on to study the images scanned by the workers of the 3.1495 building. In Movement Materials and What We Can Do(2013), a collection of photographic enlargements, he identifies aberrations in scanning, notably where part of a human worker’s body is visible in frame, shrouded in a finger condom. The index here is quite literally the index finger, the digital trace otherwise obscured by the dematerialized logic of information systems.

Taken together, Workers Leaving the Googleplex and Movement Materials and What We Can Do reinsert the human, and human interaction, to computational labor. They offer a rebuke of the fantasy of the “lights out factory,” in which a fully automated space operates without human intervention. Along similar lines, a number of films and artworks mark the scant traces of the absented human body in these otherwise fully automated spaces. For example, the robot choreography of automobile assembly becomes a spectacle in Wyatt Niehaus’s Body Assembly (2014) project, where human labor becomes that of looking. Meanwhile, Fabien Giraud and Raphaël Siboni’s 1834 – La Mémoire de Masse (2015), part of their series The Unmanned (2014 – present), reconstruct a revolt against the introduction of the Jacquard Loom at a silk factory in Lyon, the first rebellion, the artists note, “against modern computation.” Using only CG graphics, 1834 – La Mémoire de Masse incarnates a ghostly echo of the historical event in which machines perform the actions of the human agitators, “transforming a revolt against the algorithm into an algorithm of revolt.”

3. After hours

Niehaus, Giraud, and Siboni’s projects demonstrate the extent to which the digital is already integrated into previously mechanical processes. Automation is not merely the assumption of work by machines, but the deliberate absenting of human labor. This is the uncanny power of a film like Daniel Eisenberg’s The Unstable Object Part II (2022), which locates echoes of the human body in production spaces at different industrial scales, including a prosthetics manufacturer in Germany, a glove atelier in France, and a distressed jeans factory in Turkey. Correspondingly, perhaps, the trace of the human is often a primary vector by which digital labor, including digitized procedures in manufacturing and logistics, are critiqued, including in the work of Lucy Raven, Hito Steyerl, Allan Sekula, and Harun Farocki. Farocki’s Workers Leaving the Factory (1995) is especially influential in this respect: it catalogues instances in popular film in which workers are seen, however fleetingly, leaving the site of work, following the first film to be made, the Lumière brothers’ film of the same name. Hito Steyerl has observed of Farocki’s essay film: “The invention of cinema thus symbolically marks the start of the exodus of workers from industrial modes of production. But even if they leave the factory building, it doesn’t mean that they have left labor behind. Rather, they take it along with them and disperse it into every sector of life.”[4]

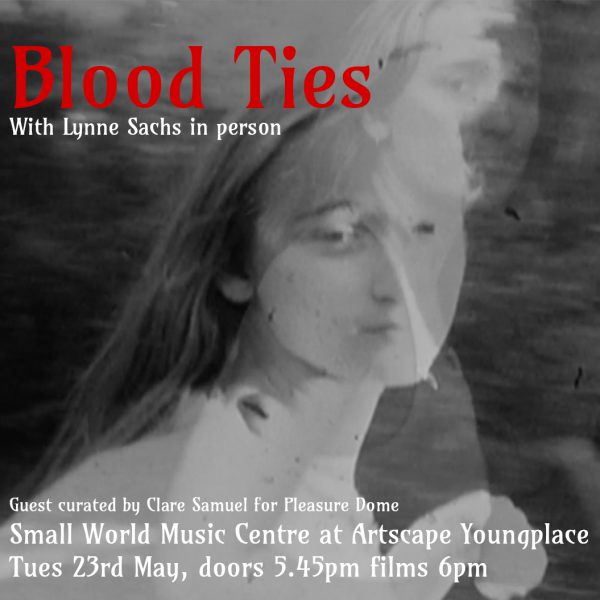

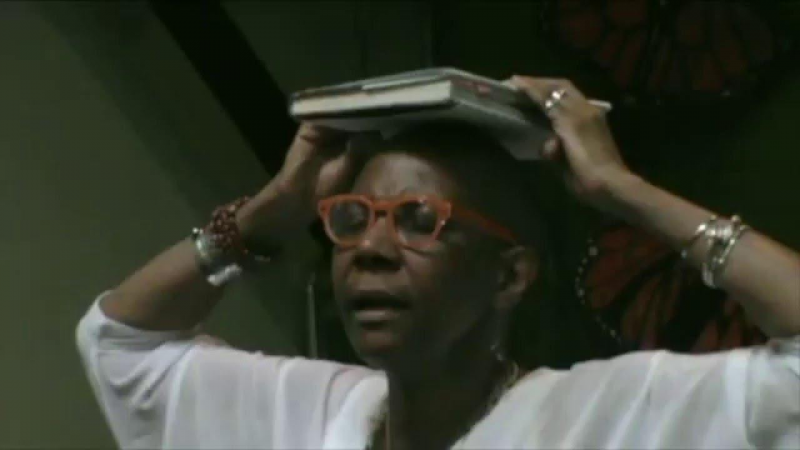

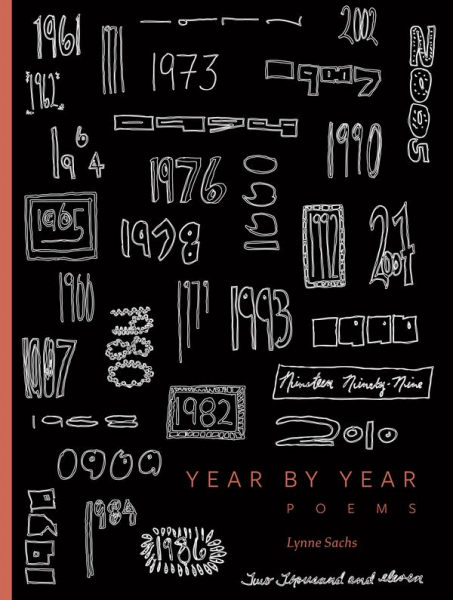

Even sleep. Lynne Sachs’s experimental documentary Your Day Is My Night (2013) traces this dispersed labor to the beds on which workers sleep—in this case, sharing the same mattress. Shift-bed apartments are a phenomenon in working-class neighborhoods, where workers keep housing costs down by sharing the same bed at different times of the day. When one works as a seamstress, or a wedding singer, another sleeps, and so on. For the film, Sachs worked with a small group of residents in New York City’s Chinatown, ages 58–78, all of whom were either living in shift-bed apartments at the time or had done so previously. Though reluctant at first to share their homes and stories—shift-bed apartments are, unsurprisingly, illegal—the subjects worked with Sachs for nearly two years to craft a hybrid stage performance and film. Sachs interviewed each person, then edited their accounts into monologues that they later performed themselves, on stage and for the film. She further created an imaginary but entirely plausible space where these residents lived together, peeling vegetables around a kitchen table, listening to each other’s stories.

Your Day Is My Night does not depict work so much as its impression, like a pillow softened by a sleeper’s head. The film depicts many shots where the environment is encountered as texture, like buildings reflected in a street puddle, or a bedroom obscured by sequins dangling from the ceiling. Instead of straightforward cinematography, Sachs’s camera adds a tactile and often hazy quality to the world as it is suggestively experienced by her subjects, who themselves describe being in and out of sleep.

Hybrid documentaries are sometimes criticized for their flexible approach to non-fiction situations and subjects, especially when the filmmaker’s subject position is different from that of her subjects, as is the case here. These critiques consist of ethical objections on the grounds of representational politics, of the sort that inhere in ethnographic filmmaking, which are heightened when the filmmaker overtly intervenes in blurring the line between “documentary”—which is presumed factual, historical, and objective—and “fiction,” which can involve fabrication, performance, subjectivity, and the potential for the falsification of reality.

I would argue, however, that Sachs’ interest is not ethnographic, which is to say that she does not aim to explicate a culture or to produce cross-cultural understanding. Rather, her goal is to bring individuals of common but different experiences together, including subjects and film crew. After recording the interviews and transforming them into monologues, the production traveled to the stage at venues in Chinatown, Harlem, and Brooklyn. Subjects became performers: they were telling their own stories, but their accounts were now refracted through the heightened artifice of theater. Shots of these performance also wend their way into the film, becoming part of the fabric of its affective experience. At the same time they reaffirm the bonds between individuals, whose sense of community is strengthened in these shared stories, through the act of storytelling itself. The point here is not for the camera to reveal preexisting reality, but for it to provide the occasion by which individuals can gather and where experiences can be shared. As with the structure of work in Nightcleaners, where workers are kept separate from each other by assigning them to different floors, the conditions of work and off-hours rest in Your Day Is My Night present real obstacles to collectivity. People are separated from each other by work, by shifts in a shared bed, by sleep. The film and performances, over the years-long duration of the project, provide the opportunity crucial to fostering a sense of community. Such community is by no means guaranteed, but this is the condition for its possibility.

I am hopeful that film can continue to provide such occasions for coming together: on a set, onscreen, and as viewers. We should not take for granted that film, too, is a site of work, and the horizon of struggle includes movie theater cleaners who vacuum and sweep the aisles overnight, and who, as migrant laborers with vulnerable immigration status, frequently face wage theft, hazardous working conditions, and exploitation.[5] To be in the audience of a film, furthermore, is to be kept in the dark. These are among the conditions of a cinematic infrastructure that maintains the atomization and isolation of people, and that mirrors a broader social organization of work under capital, where people are kept largely separate from each other, and are discouraged from talking about, reflecting on, and organizing around their work. Sometimes it is only in the off-hours where we can catch a glimpse of the possibility of collectivity onscreen, or, as is more often the case, in the glare of a laptop monitor, in bed, in the moments before we turn over for sleep. Perhaps we will glimpse a new vision of what life and work could be. Perhaps, tonight, we will dream new dreams.

[1] Christa Blümlinger, “Non-Places, Nomads and Nameless Ones: Notes on Something More Than Night,” trans. Michael Ritterson, in Postwar: The Films Of Daniel Eisenberg, ed. Jeffrey Skoller, Raymond Bellour, Nora Alter, and Tom Gunning (London: Black Dog Press, 2010), pp. 150–165.

[2] Raymond Williams, “The Meanings of Work,” in Culture and Politics: Class, Writing, Socialism (New York: Verso, 2022), pp71–90, citation on p90.

[3] Andrew Norman Wilson, “The Artist Leaving the Googleplex,” e-flux journal #74 (June 2016).

[4] Hito Steyerl, “Is the Museum a Factory?” e-flux journal #07 ( June 2009).

[5] See Gene Maddaus, “How America’s Biggest Theater Chains Are Exploiting Their Janitors,” Variety, March 27, 2019.