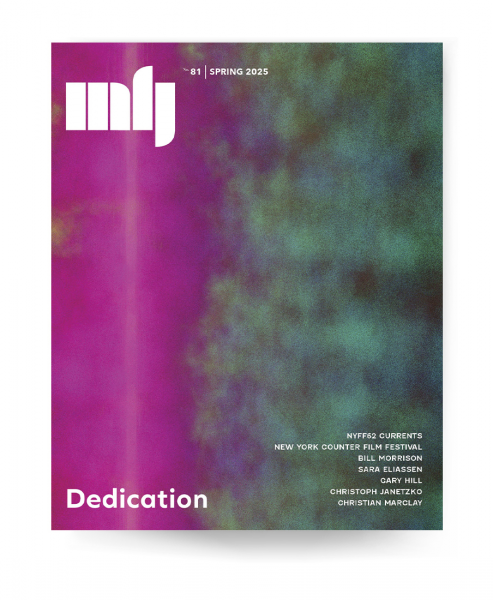

MFJ 81 “Dedication”

This item will be released April 10, 2025.

Spring 2025

This edition of the Millennium Film Journal is marked, above all, by grief. We felt it painfully during our fall screening at Anthology Film Archives in the immediate aftermath of the 2024 presidential election, and later as wildfires tore through Los Angeles, devastating members of our community directly and irrevocably. Loss is a part of human life, always, everywhere, but today there seems so much to mourn, as wars rage, ecosystems collapse, injustices multiply and worsen, and hopes of humanitarian justice founder.

Excerpted from Nicholas Gamso’s Introduction, MFJ 81 “Dedication” (Spring 2025).

Remembering Gunvor Nelson

Gunvor Nelson was a profound presence in my life – a teacher at the San Francisco Art Institute first and then for decades a dear friend. Her films made you think about everything from the taste of a shiny green apple to the mortal coil. Whether using a light meter or working with the laboratory on the timing lights for a new film, Gunvor relished every aspect of her art, including the technology. I would sit with her for hours in front of a 16mm editing machine, knowing that I was learning from a brilliant, committed artist with the most lucid, precise advice.

“Before you shoot film, it is helpful to think through what style of editing would be most appropriate so that you will not leave out necessary liaisons or steps.”

Transitions were extremely important to Gunvor. She was always thinking about how to enter the front door of an image and how and when to get out. A shot was like an airport and the arrival and departure times of every single plane were critical. Otherwise there might be too much chaos on the tarmac!

“Surprising solutions can be had with the most deficient of material if you let it speak to you, if you learn what really is in the film. Sharp jumps in the editing can be, at the right places, most exhilarating.”

One of the most lasting suggestions Gunvor made to me was that a filmmaker should always return to their outtakes just before the completion of a film. These “mistakes” that were initially disregarded become extremely useful punctuation – like a period or an exclamation mark – that assists the completion of a visual thought.

Gunvor’s movies also made me think about being a woman in the most visceral ways. Here film “Schmeerguntz” (1965) captured the raw, messy ecstasy of being a mother, and her film “My Name is Oona” (1969) celebrated the fierce passion of her daughter Oona Nelson, inspiring me to shoot 16mm footage that spins, dances and, soars with my daughters Maya and Noa.

A few years ago, I traveled to Gunvor’s home in Kristinehamn, Sweden, to spend time with her as I was making my film “Carolee, Barbara and Gunvor” (2018). We often found ourselves in her lush garden just outside the back door. On our last day, we were standing in front of a patch of snapdragons when she decided she couldn’t resist being my teacher again. She noted that everyone shoots colorful, living flowers. It’s more interesting and sculptural, she explained, to film the dead ones.

I am reminded of Gunvor often – in dreams and in my consciousness as an artist. Like Cézanne, she was more intrigued by the shapes that surround an object than the object itself.

“Study negative space.”

Gunvor once explained to me that when you finish editing your film, you will feel ecstatic. Then, there will be a profound sense of loss. To be inside the making of a film is an incredibly consuming fusion of the intellectual and the artistic. No matter what is going on in your home or in the world beyond, you have your film, and that, sometimes, is enough.

Lynne Sachs

Remembering Narcisa Hirsch

I arrived in Buenos Aires in the summer of 2008, ready to immerse myself in a city with a reputation for celebrating avant-garde films with the same intensity that Hollywood lauds mainstream movies. Within the first few days of landing in Buenos Aires, I started to hear about this extraordinary 80-year-old woman who lived at the vortex of all things experimental. She had not only spent a life-time making her own work, but was also supportive of other film artists whose 16mm prints she collected and exhibited in her home. Her name was Narcisa Hirsch.

From the moment we met, I knew that I wanted to spend as much time as I could with this woman who was so candid about everything surrounding film form and feminism, in equal measure. Clearly, she had a profound interest in unraveling the ontology of cinema and challenging the way that film as an art had been hijacked by the entertainment industry. She was always thinking about the camera’s ability to rearrange reality and the way it allows us to better understand how we think and move. She made it clear that she had her own perspective and it was clearly female.

One morning I went to Narcisa’s home in the neighborhood of San Telmo. Knowing how much she loved children, I brought my camera and my young daughters Maya and Noa. She immediately explained to us that painting on an easel had “died” in the late 1960s. Consequently, she’d made and documented far more radical feminist performances, what people were starting to call “Happenings”. She created Marabunta (“swarm of ants”) collaboratively in the Buenos Aires theater where Antonioni’s Blow Up was premiering. In Munecos she gave away 500 baby dolls on the streets of London and New York City. Narcisa vividly described her first witnessing of Michael Snow’s Wavelength, fully aware of how influential this seminal 16mm film would be to her film Taller, a starkly structuralist, yet personal, survey of her own studio space. She showed us her visualization of Steve Reich’s Come Out which she integrated into a filmed document of the sound piece as it plays on a portable record player. In her mind, purchasing films by artists she respected was the best way to support the work she loved. She proudly swung open a closet which contained the work of Carolee Schneemann, Su Friedrich, Stan Brakhage and so many others.

Narcisa was exquisitely aware of what she was doing. She committed herself to filming her daily life both in the city and on her farm in Patagonia — close ups of leaves and water, her feet, a fly, her shadow in the sand as she carries her film camera, cherries on skin, a fly, a mouth luxuriating at the taste of fruit, a baby on the grass, a breast, and a belly in the sunlight. As long as she was world famous for 50 people, she was happy.

Lynne Sachs