https://schneemann-oral-history-dev.netlify.app/lynne-sachs

Downloadable PDF available here.

Lynne Sachs: I’m just going to pour my tea and then we’re going to get going on this. We could just keep talking about the South.

Erin Zona: Do you ever go back?

LS: Well, I do because my mother lives in Memphis. But is it okay for me to tell you this? … Actually, this relates to Carolee. So, you know, Carolee was involved in various anti-Vietnam War efforts, collective efforts. Omnibus projects. Viet-Flakes [1962–67]. Do you know that film of hers?

Read more about this artwork

EZ: I do.

LS: I think she was really interested in how artists came together [around] issues that they cared about. So I’m going to tell you about something that I’m doing next week. [It’s about the] control of women’s bodies. Very fundamental to Carolee. So once abortion, the whole abortion issue, was transformed by the passage of the Dodds decision in the Supreme Court [referring to the June 2022 decision in Dodds v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization]. As you know, many states in the United States now have proclaimed that women can no longer make their own choices about their bodies.

So a woman at UCLA put out a call for artists who work in film to join her in an omnibus project in which you would go to a state where abortion is no longer legal and make a short, sort of personal film. And the premise of it for everyone is the same. So someone’s going to North Dakota. Someone went to Kentucky, probably Arkansas. There’s about eight of us. I’m going back to Memphis and I’m doing this performative piece at a building which is called Choices, but it’s been shut down. I’m working with 12 probably, at the most, women. … They’re going to be in robes so from the back we’ll see their bodies, but you won’t see their faces at all. And they’ll be in different poses standing around the building. We have to shoot it very quickly because it’s on a busy street. And so if people see us there, especially women in robes, that could create a big … that could be potential for tension.

EZ: Yeah.

LS: So anyway, that’s what I’m doing. I have to get releases, even though we’re not seeing anyone’s faces … and they don’t even have to put their name in the credits. But I’ve learned from the women who helped me get the people together that they’re all so excited. They’re saying, “thank you,” because they care about it.

EZ: You’re doing that next week?

LS: Yeah, I’m doing it Saturday. A week from today. Everyone who’s shooting a film like this is shooting around a building or doing something related to a building that no longer provides these services. … Then the other part is that everyone has a voiceover of someone who’s been affected by this decision. I actually have two women. One was a woman who performed abortions through Planned Parenthood for years and is an activist in the Black community. She’s an OB-GYN. And then the other person is a woman who used to stand and accompany women who are getting out of their cars and walking to the front door of this building, protecting them. Now there’s no longer a reason to do that because there’s no services in the building. She’s now a driver, like what people [used to] call a Jane. And she drives people all the way to Illinois.

EZ: Wow. Amazing.

LS: Yeah. So she’s the other voiceover.

EZ: How exciting.

LS: It has to happen quickly, but I’m looking forward to it.

EZ: That’s great. Thanks for sharing. … Can you tell me a bit about who you are as a filmmaker and how you arrived at that choice as an artistic genre?

Listen 7:48LS: I have been making films for exactly 40 years. The very, very first film that I made was a Super 8 film in 1983. It really was a vessel into which I could discover something about myself. Now, I had never watched movies that way before. But a few years before that I had seen work by Chantal Akerman or even the author Marguerite Duras, and I had one of those “bing” moments where I said, “Oh, wait, women make films?” People make films that are personal in the way that writing a journal can be, or drawing or painting or taking a photograph? It had that intimacy and also that sense of autonomy, that it can be an extension of your imagination in this very interior way. But then it also takes you into the world and has a fluidity between your home space and your public self. And that was just a shock to me.

I actually took a Super 8 class at an art school in New York City. I’d already finished college and I finished the film. I remember the teacher said to me, “Oh, you must have been a liberal arts student,” because the film didn’t really depend on a kind of script with a punch line at the end. It was much more associative and textural and very much about process. I probably couldn’t have used any of those words before, and it actually featured my closest friend who had grown up with me in Memphis. We were both in New York at this moment. We were trying to figure out who we were going to be in our lives, and the film gave me that possibility. In some ways I’ve been doing that ever since. They’re not all in any way autobiographical, but they are imprinted with a moment in time. I love that working that way can give me solace and awareness and can give me an opportunity to think about politics and other things beyond my own sphere. And poetry does the same thing for me. I just like seeing how images and text can confront each other and embrace each other.

EZ: Is there a moment in time, as you were becoming the artist that you are today when you were … at the beginning of your professional career, where you remember a work of art or a film that was really influential to you? That still is part of your forming, I guess?

LS: Hmm. Okay, I’m going to answer this question and you’re probably going to say, “Oh, she planned that,” but I really do mean it. In 1986, I made a film called Drawn and Quartered, and the film was shot on the roof of the San Francisco Art Institute where I was a student. I asked my then boyfriend to take off his clothes. I took off my clothes and we each took the camera back and forth and filmed each other. And I used an old regular 8[mm] camera and didn’t develop or process it in the traditional way, so it [ended] up being a frame with four images … quartered. And so I played on that word “drawn” and that form of punishment, to draw. Like when you draw and quarter, you split someone into four pieces. It’s very violent. But in this case, it was actually kind of like a love poem.

I think I probably had seen Fuses [1964–67] by that time. And so the idea that you were both holding the camera and in front of the camera … oh, I’m almost positive. I had to have seen it, because in 1987 I went back to Memphis to teach a summer class–not that I really knew anything, but, you know–to some college students. … I was pretty young then. But anyway, I remember showing Fuses, and I can tell you that was actually problematic. So I know I’d already seen it, and I know that I had thought it was revelatory and that it was a film in which both the man and the woman were engaged with each other, celebrating each other. I guess I could say empowered in some ways, but also not empowered–just being. Should I tell you about showing the film?

Read more about this work

EZ: Yes … and also I would like for you to speak to Fuses for you as an audience member and about [the film] in the wideness of the world.

LS: Fuses had been really important to me. But I have to say, at the same time, I read Laura Mulvey’s article [“Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema,” 1973] … on the male gaze, and it was extremely important and very influential. [Mulvey] said that whether or not you’re a woman or a man or now we would say are nonbinary, you still pick up a camera and you replicate the male gaze because you’ve been so influenced by culture that you have to really reconfigure your way of seeing in order to confront that. And it’s not any more powerful for men than it is for women because we’re so conditioned that way. … [Mulvey asked,] What was it to frame the body with a camera, whoever’s body, and how was that presented in a somehow male inflected way? That was a really important essay. People still read it today. … And so, to read that and then to see Fuses at the same time was like finding a manifestation of what it was to make images from a female perspective. To say, “yes, we understand what you’re saying of popular culture, Laura Mulvey. But this is what it is to experiment.” That’s why I actually like the [phrase] “experimental film,” because you’re pushing, you’re trying out new things and you don’t know what the answers will be. So those two experiences coming together were so important to me.

LS: I remember showing Fuses to, I think, a group of young women. And I was, gosh, like 25 or 26 at the time. I guess I was just teaching a workshop on filmmaking in Memphis. I showed Fuses and I didn’t frame it. I just showed it because I thought it could stand on its own; I wasn’t testing the audience or me. But you know how that is. Like, “let’s talk about who Carolee Schneemann is,” and the group of students were very critical of it, and they didn’t like that she showed her body in this very sensual way. I got very defensive. … I continued to show it–I never hesitated–but I wasn’t at that moment prepared for the nuances of what it is to be a feminist, and now I think I can acknowledge that different women have different ways of representing the body. And Carolee’s way suited so many people. She’s a hero, but other people have ambivalence about [the film], or, let’s say, critique. But that makes the work just as strong to me. So that was an interesting experience. And I was very deflated. I was, at the time, so upset. I couldn’t even find the words because I just wasn’t prepared to have to defend that film the way I had to.

EZ: And so was that a college class? …

LS: I think it was college students.

EZ: Okay. And it was even after you framed it and contextualized it within the theories that you said. Were people open to it or was there pushback?

LS: I think they were more open to it. But now, I have to say, I’m remembering it the way I want to remember it. I really don’t know. I don’t remember what happened afterwards. I just remember the film was over and I thought we’d have this really exciting, enthralled conversation. And they turned to me, and they were a bit hostile. We’re in a period of reflection on identity and gender right now. But that was also happening in the ’80s. So that was a period in which women probably thought [about] the ways you [could] dress to make yourself less sexual or less desirable. You know, like how to cut that, the male gaze.

EZ: Yeah.

LS: I think that was definitely an entry point for me, with Carolee. It was because of all the ways that she would continually prove to me that I have patriarchal eyes, even if I’m a lesbian, even if I have this much experience in the world, that her ability to stay sharply aware of that and constantly be ready to sort of flip the conversation to make you see, right, that way. And I think that combination of reading the Laura Mulvey piece and looking at Carolee’s just was an explosion in our ways of thinking about what we call somatic cinema. What is it to have the body centered but not objectified?

EZ: It’s very interesting. And I’m not a filmmaker, just so you know, but I understand large concepts around the male gaze. …

LS: I’m neither a theorist or historian.

EZ: Me neither.

LS: But, you know, I like to explore.

EZ: … I’m curious, do you go to the theater and see films a lot?

LS: These days … I watch a lot of film, but I would say honestly, I watch more at home. And I’m still excited by the moving image, and I love being in a room with people, but I don’t necessarily find that it’s compromised watching it in a more private space. On the other hand, I think for that absolute immersion, there’s just nothing like that separation you feel and the fact that a theater space is so hermetic and so you’re contained. It’s the psychic nature of the film. Like you’re at one with the film, or theater, or any performance experience of that sort. So I have to say I could go more. But luckily, in New York, we do have so many alternative venues that aren’t just for commercial cinema and …

I’m going to weave in a story about Carolee here. I always invited Carolee Schneemann and Barbara Hammer to any kind of film that I had; they were on my New York email list, let’s say. And that could be hundreds of people. They were the only two people who consistently would write me a note saying, “Dear Lynne, I’m so sorry, I cannot attend your whatever it was. I wish you the best and I hope to come next time.” It was done in the most polite way, and it was like a deep acknowledgment. And both of them did that. It’s like their moms trained them to do it or their fathers. Something about them compelled them to show respect for the other person. To be kind of formal in that engagement across a generation. It just was very touching how consistent that was.

EZ: I love that.

LS: Have other people told you that she did that?

EZ: Well, it’s funny that you mention that. Would it be through email?

LS: Yeah.

EZ: I love reading correspondence in general, in archives and around individuals that I’m, for whatever reason, intellectually interested in. And I always have found myself admiring that when I am working in someone’s archive and I find evidence of a thank you note over something like this. I try to be like that. I wasn’t trained that way. We never did thank you cards in my family. It’s not as if it’s part of my …

LS: Yeah. Can I show you something?

EZ: I’d love to see it.

LS: I am obsessive about letters. Even emails. To me, emails are letters. So I save letters, all my letters. I have for a few years. … What I do every year is, if I get a good letter–I’ve saved everything from Carolee, for example–I just make a PDF of it immediately, especially if it’s a whole thread and then in January of the next year I print them. And I mean, that’s not a waste of paper. It’s only one [year]. That’s not that much paper.

EZ: I really admire that you’re doing that. …

LS: I think it’s really important. And you’re an archivist, so you would probably agree.

EZ: Do you have any pets? An animal that was meaningful to you for some reason?

LS: … I’ve had a cat, a couple of cats, for the last 20 years. And I used to talk to Carolee about cats. She had very strong opinions about what to feed your cat and the connections that you had [to] your cat. And I do have a very strong memory of being in the hospital with Carolee after she broke her hip in about 20–2016 or ’17 I think [referring to Schneemann breaking her hip during a lecture at NYU in 2014]. She actually gave a lecture that I invited her to give, and I saw her fall.

EZ: Oh, no.

LS: Yeah. She gave the lecture with the broken hip. Did you know that?

EZ: I think I did [hear about] that.

LS: And then she went to the hospital. She actually wanted to go out for dinner too!

EZ: Of course.

LS: Anyway, when I went to see her in the hospital, we talked about things. You know, what’s good to feed a cat? What do you do with an old cat? We had lots of conversations around cats. And of course, I knew about Fuses being sort of the point of view of a cat. But the other thing I’m going to say that she didn’t have is that I have three pet water frogs. I bought tadpoles in 2004 for my daughters to see how tadpoles turn into frogs, and I still have those frogs in basically a hamster tank.

EZ: Here?

LS: Here, upstairs. I just fed them today. So I have 19-year-old frogs, water frogs.

EZ: 19?

LS: Yeah.

EZ: Wow. I did not know that they lived …

LS: I think I should win some kind of award or recognition. Maybe some of the oldest frogs on earth and they’re upstairs.

EZ: And how big are they?

LS: They’re like the size of your palm.

EZ: Wow. What are their names?

LS: They don’t have names. They’re just called the frogs.

EZ: How funny. I love it. … I have three deer that eat in my backyard. And I just named them all Tina and I call them the three Tinas.

LS: Oh, that’s good. So it means that when we go out of town, somebody either comes by to feed the frogs and the cat. But a cat, you can’t leave for that long… a couple days. The frogs, you could leave as long as you want, as long as you just feed them. And they have marbles in the tank because well, to keep them entertained. I always think I’m going to forget to feed them, and so when I walk by the bathroom where they are, they’ll move a little bit and then it jiggles the marbles and it reminds me, I usually remember, but sometimes I think I might forget. And so those are my animals.

EZ: I love it. Thank you.

LS: You have three deer and I have three frogs.

EZ: You might have touched on some of this, but feel free to repeat yourself. How did you first become aware of Carolee? How did you meet for the first time?

LS: I first became aware of Carolee Schneemann because of Fuses and because I was living in San Francisco and she was so important to the whole pedagogy of the film department at the San Francisco Art Institute. Any course on avant-garde film would probably include a film of hers. It could be Plumb Line [1968–71], or it could be Viet-Flakes, but it would find its way into the syllabus, let’s say the curriculum. At that point, people, at least in San Francisco, were really talking about her as a filmmaker. They weren’t talking about her as a painter, that’s for sure. It just didn’t come up. And I think that happened to her disappointment, you know. … Then in 1991, she was a visiting artist at the San Francisco Art Institute and it just so happened that my friend Mark Street, who ended up becoming my husband–we’ve been together all these years–was in her class. Somebody suggested to her that she invite me because I had made a film called The House of Science: A Museum of False Facts. It was a collage film that explored how art and then science were culpable in forcing women to look at their bodies in a certain way. From menstruation to the shape of your body to how you imagine your future, things like that. … I don’t think she had seen it, but she asked me to come show it in the class. We sat in front of the class having a great old time talking, and we didn’t talk to the students that much, but they were there. And so that was the first time we met. And that was probably the fall of 1991. I did not have her as a teacher because I had already finished at the Art Institute a couple of years before, but Mark was in the class … [and] he got to know her as a student.

I was not in touch with her until years later because I moved here to New York and I was involved with the Filmmakers Co-op and so we would often show her films and sometimes she would come through. I ended up being on the board of the Co-op for 17 years. Carolee’s work was in the collection, and she was around a lot, and coming to some of the Co-op events. You know what, I kept wanting to go to her house to film with her, but she was so busy. And finally, she let me come film when I made Carolee, Barbara and Gunvor. We spent time together then and we kind of became close and spent a lot of time talking on the phone when she was going through a lot of struggles. She gave me some good advice about my own daughters. Sometimes admonishing, sometimes supportive. She was very open about those things. And I would go up to–what’s the name of the–

EZ: Springtown Road.

LS: Springtown Road. I would go through New Paltz and to her house and spend time there and shoot Super 8 film with her and go to the movie theater or out for dinner. Things like that.

EZ: I wanted to ask you about [the house], because Carolee had such an important relationship with her home.

LS: Yeah.

EZ: I would be curious about your first visit there. And maybe if there was anything significant about the tour that she gave you of her home and studio, and what animals were there at the time.

LS: I love that you asked about the animals. The first time I went to her [house] was probably 2016. … [We] went out to the other building, the studio, which she was very proud of. In some ways, I got the feeling that it was more storage than active. That it was too new and too kind of austere compared to her house. I didn’t necessarily get the feeling that she would go out there every day to her studio. But when I went to her house … I’ll never forget, one day we were sitting outside on the porch and I saw a blue jay that the cat had brought in. I have a picture of it. It’s so beautiful. The cat had brought and left [it] on the porch, the way cats do. And, you know, most people would see a dead animal and want to get rid of it and this dead animal was definitely going to stay there for a long time, because I think she admired the bird alive, but she also admired the bird as an object and as a connection to her cat and to nature, and to all the rites of passage for all of us. And it wasn’t sad at all. It was just kind of glorious that it was there.

EZ: I love that story because it is something that I think I learned from Carolee. Especially with relationships to animals that are our pets. That we are responsible for, but in Carolee’s world, the cats were themselves. It wasn’t as if they are a pet in the same way that someone else might have a pet. I mean, La Niña, probably the cat who was the one who killed the bird, had this agency. And, you know, magic, for lack of a better word, that Carolee would see in an animal. I love that. And that’s something that I learned, as you go through grieving processes with animals where they grow old and then they die. And you as a human have to you participate within all of that and observe death. And it’s her way of being in the world, with nature… [it] was something I really responded to, having known her as a person.

LS: So you did get to know her in the years that you…

EZ: I met her in 2017. I’m 43, so I think I was first exposed to her work through the Angry Women book; there’s a chapter about her.

LS: Yes! Oh yes. Oh, my God. That’s a classic.

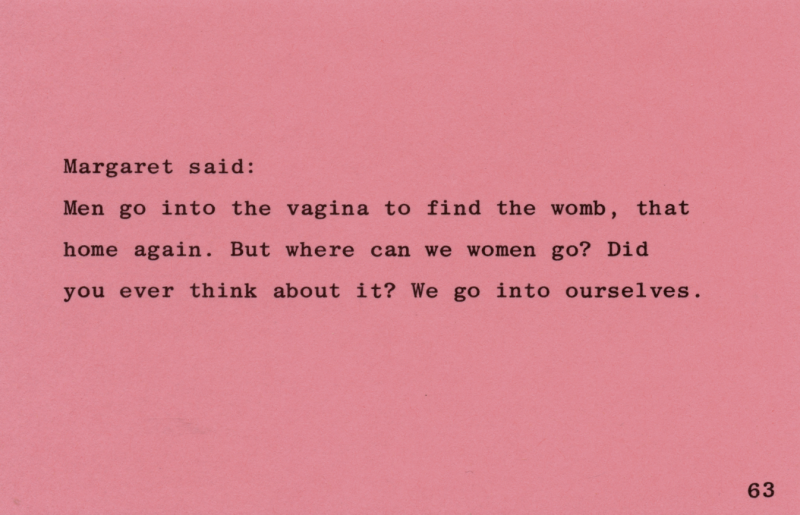

EZ: … 1996 or whenever that book first landed in my hands, it was fairly new. When I got my job at Women’s Studio Workshop [residency and artist’s book publisher in Rosendale, NY] and was moving to the area, I discovered that she lived just down the street. She would make prints at the studio and knew the founders of Women’s Studio Workshop. I very quickly sort of forced people to introduce me to her and then we did a project together. We did a reprinting of Parts of a Body House Book that Women Studio published, and so I worked with her on it. She died while we were still making it, but we finished it after. She had given me permission to finish the book if she died while we were making it. We had just finished all of the creative components, the paper colors, all the ways that things were going to land in re-printing right before she died.

LS: What is the name of that book?

EZ: It’s called Parts of a Body House Book. It was originally published in 1972, and we did a pretty straightforward facsimile of the copy that she had that she has in her house. And I think it’s still in her home collection.

LS: Can I order it from you all?

EZ: It’s an artist’s book, so it’s a little more on the expensive side because it’s handmade …

LS: But there are still ones left?

EZ: Oh, yeah, … we still have a few. We only made 90. …

LS: Lucky for you to be involved.

EZ: Oh my gosh, I was so happy. I told her I wanted to do a project with her. I said, “What do you want to do?” And then she said, “I have a book that no one has seen.” And she went up and got this book and she said, “We should reprint this.” And I was really … I loved the project. It’s one of the proudest things I’ve done as publisher, for sure. Definitely.

LS: Oh my God, yeah.

EZ: La Niña actually finished the book because Carolee was going to do these paintings on the back of each book. She died before she was able to do that. So what we did was we had La Niña walk across with this beet-juice-and-mud mixture that we had made.

LS: Oh, I love that. That’s totally in her spirit.

EZ: Let’s go back to … you mentioned the cat, the blue jay. I love that. That’s a great story. When you would visit her in New Paltz, you were filming, but would you sit in the house together?

LS: We did sit in the house, mostly in the kitchen. Sometimes I would sit and she would actually do work. … She was always very attentive to responsibilities that she had and phone calls she had to take care of and trips she was organizing and taking care of business and things like that. So sometimes I would just kind of be there. I don’t think she felt obligated to entertain me at times. And also, she was not well, so sometimes she would just lie down for hours, and maybe La Niña would be on the bed. And then she said I could film. That’s why I have some nice footage of the house without her in it, [and] some of it with her in it. I was just trying to engage and fill up my time and I knew it was special. I remember going upstairs with her and she really didn’t have the energy to go upstairs, you saw where she had all those pictures, you see it in the film, where she had all the pictures from the war in Syria and the devastation. She was trying to figure out how to integrate that and what the dialogue was between aesthetics and horror. I think she was very torn about that. She was–I’m being kind of literal–she was tearing those images. You’ve seen them, right?

EZ: I have … in the upstairs studio. …

LS: Yeah. And so you had that [studio] room and then you had that other room that was more like slides and archival things. But I could tell … maybe I’m reading into things, that it wasn’t just that she was feeling physically weak. It was that the images themselves were not just painful, but that she didn’t know. … I don’t want to say she didn’t know what her role was… she was trying to figure out how to be with them, supportive of them, critical of them. What was it to be… constantly to be an artist with such deep concerns about the world? The tearing of it seemed so important, because it’s also a violent thing to do, to tear an image. It’s both violent, but it’s also being willing to touch. I mean, you probably know that, right after September 11th, she made [an artwork] with the image of the person, the falling body [referring to photographic grid Terminal Velocity, 2001]. … It was a man jumping out of one of the World Trade Center buildings before it fell. And it was a kind of iconic image of, do you know about this story?

Read more about this artwork

EZ: Go ahead and tell it.

LS: It quickly became an iconic image of desperation. Someone throwing themselves out of a building, you know, from 90 stories above. I remember seeing [Terminal Velocity]. … Some people were very critical of it because they felt that 9/11 couldn’t be touched. But other people said, what more of an homage to the death than showing this figure, this last gasp before dying of this single person. And also, as we know, it’s much more possible to feel empathy towards one person than towards 2,000, in a way. You can be upset about the aggregate of 2,000 people dying, but to see one person jumping, you feel this cathartic relation. You feel, there but for the grace of God, “I would have jumped.” … You feel this individual. So it had all of that. But at the time, I think that she was criticized for using that image in an art piece.

EZ: And why do you think… I mean, why would that not work in a place like New York versus…?

LS: Especially in New York, people were very sacrosanct. You know, [taking on a mocking authoritative tone], “That is very precious, and you can’t touch that.” And, you know, the more people said you can’t do something, she was going to do it. She wasn’t trying to draw attention to how you might feel about the people who were responsible for the building coming [down] … it wasn’t an argument. It was pathos, right there in front of your eyes. But in New York, that was problematized or complicated. … Looking back on her work, her video work was often dealing with political subjects. And I mean this as different from her film work … for example, I’ll tell you [about] that piece at Eyebeam [Devour, 2003] … [When] I went to Eyebeam, it wasn’t quite set up. She was installing it herself. And this is in 2003. You know, [even] a person of that stature, because she went from painting to video to sculpture, she didn’t necessarily find her work at that point in the most lofty of situations. I mean, Eyebeam was a not-for-profit. It’s hard to imagine now because she just had that show at the Barbican [referring to Schneemann’s 2022–23 retrospective Body Politics] and, you know, her work is so elevated. But even in the early 2000s, she was definitely a one-woman band doing everything herself.

EZ: It definitely felt that way, at least when I met her. … I met her after the show at MoMA [referring to Schneemann’s 2017–18 retrospective Kinetic Painting]. Do you think, for you, that was a significant …?

LS: The PS1 [exhibition]?

ES: PS1, yeah.

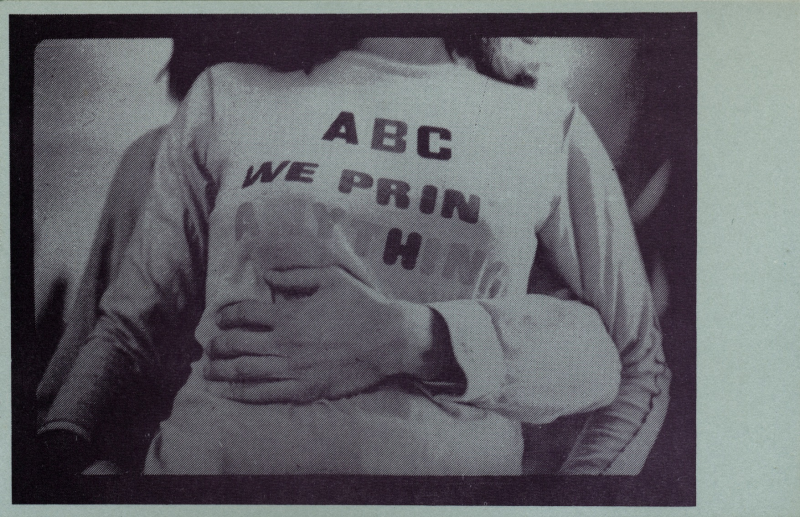

LS: Well, I went to the show a couple of times, but one of the times I took my mom. She was here from Memphis, [and] it was so important to me to introduce my mom to Carolee’s work and to convince her that this was important to me as an artist and as a feminist and as a thinker. I pushed my mom. And in a way, it wasn’t the right way to do it. [The artwork] either speaks to you or it doesn’t. She had pieces in which she used index cards and she talked about … do you remember?

EZ: It’s ABC – We Print Anything – In the Cards [1977]. It’s one of my favorite works of art.

Read more about this artwork

LS: Can you describe it for me?

EZ: It’s an artist’s book. And I think that what you’re speaking to, there was a projection that was showing the cards. And then, I don’t know if [it was in] that exhibition, they had the film of her reading the cards. I know she’d done several iterations of it. … ABC is Anthony [McCall], Bruce [McPherson], Carolee. It is about 100 plus cards that are different colors that are her navigating through the relationship with Anthony ending and her relationship with Bruce starting. For that show they represented it through a slideshow of the images.

LS: But the cards, some of the cards were there in the vitrine.

EZ: Some of the cards were there, yeah. And the book itself, outside of the performance …

LS: I want to get this book too!

EZ: Oh my gosh, I [am] on a waiting list for this one, where I say … “Collectors, if you ever find this book, a copy for sale, you have to let me know.” It’s so rare to find. It’s in collections.

LS: Oh, so I’m not going to find it.

EZ: It’s museum stuff. I don’t know what your collection budget is, but …

LS: No, I won’t find that unless you reprint it.

EZ: [Laughter.] But anyway, you were saying …

LS: It’s so interesting the way institutions can validate people. And yes, it was at PS1, so I have a feeling she probably felt that was one step down from being … like you said it was at MoMA.

EZ: I know I did.

LS: But it wasn’t at MoMA.

EZ: You’re right.

LS: It was at PS1 MoMA, and that’s in the borough and that’s a different thing. And I have a feeling she felt a little … and I’m guessing. I did not talk to her about it, so we’re just projecting. But that building has a quaintness. It’s very important, but … it’s not MoMA, you know? It’s not the international tourists. Museumgoers might go, they might not go. So it’s interesting it wasn’t at MoMA. And the other thing I’ll say, like when she got a recognition for lifetime achievement from the Venice [Biennale], I remember talking to her about it … and she wanted to go to Venice and get her lion or statue, but they weren’t even giving any money … but a prize. It was more like, “Yay! You get a lifetime achievement award.” And she said, “But I need the money.” But she still went because she wanted to be connected to that.

I have one other story to tell you about ways that Carolee really fought for herself. Is that okay for me to tell you?

EZ: Of course.

LS: In 2000 or so, I was living in Baltimore and teaching at Maryland Institute College of Art, and my husband taught at University of Maryland, Baltimore County. Carolee was invited to come as a visiting artist, and two things happened that I’ll never forget. One was that she was giving an artist talk and at the end a student in the audience stood up and asked, ”Do you feel like you’re a failure because you didn’t have a child?” And you could tell that had been asked before, and it was not devastating to her–to Carolee–but it was insulting. I think the student, young woman, felt that she could ask it because so much of the work was autobiographical, so much was about the body, so much was about women’s anatomy, so she maybe felt that it was all in the same voice. I remember that was so–not naive–but so conventional as a way of thinking, of measuring a woman’s success. You know what I mean?

EZ: Yes. And what did Carolee say? I can imagine her.

LS: Like you’re horrified. She just said, “I didn’t want children. I was so focused on my work that you’re asking me the wrong question. I didn’t feel ever that I failed. It wasn’t part of what I was trying to do.”

EZ: Yeah.

LS: So that was one thing. But at the same time, she had to leave a little early because they were taking a picture at the Whitney Museum of important artists of the day, including Rauschenberg and probably Jasper Johns and others, and she had been invited to be a part of this big photograph, a group picture. And she knew that she’d probably be the only woman, or maybe there was one other, I don’t know who. So she had to rush back to be in the photograph.

EZ: Wow.

Photograph by Timothy Greenfield-Sanders.

LS: And I think she knew that she needed to carve out her place for us. …

EZ: To go back, I have some questions about New Paltz and the house. When you visited her there, did you all go out to eat? You said you went to the movies. …

LS: We went to a movie. I don’t know why I remember this, but I feel like at some point we sort of held hands in the movie. I was just like, “Oh, this is so thrilling. I can’t believe this is happening.” And I mean, it was just affectionate. And then we whispered to each other that we hated the movie and we left early.

EZ: Do you remember what movie it was?

LS: No, I don’t remember. It was so bad. It was a totally mainstream commercial movie, and neither of us were interested. It was just like, you know, you asked if I like to go to movies. It was a nice ritual that actually wasn’t that good. And then we went to dinner. There was a place near town, sort of a farm-to-table, beautiful restaurant. And it was there where I was talking to her about what concerns I had about my girls’ love life because, you know, I was just kind of like letting it all hang out. And she said, “You need to let them have their own life.” She kind of admonished me in a sweet way.

EZ: Are there any other things that you would want … that come to mind if you think about her home or visiting her or the filming?

LS: Oh, let me think. I mean, I think one of the wonderful things about that house, just to me, was that it allowed the outside in and the inside out. Like the windows always being open and the sense of the vines almost coming through the window. I liked how it was in the land, and that she’d let it age without updating the oven or the ceiling or anything. I liked that you saw time pass there and it had that beautiful glow to it. I felt it was so connected to even the dirt outside, you know, and she wasn’t fussy in any way with all of that, even though she knew that people would treasure that building.

EZ: I can relate to what you’re saying, especially because there are a couple of scenes in Kitch’s Last Meal [1973-78] where she’s dumping water on the porch and sweeping the water off as a way of mopping dirt off of the porch and it’s kind of an old-fashioned mopping, way of cleaning an outdoor porch. And she’s hanging laundry in a couple of parts.

Read more about this artwork

LS: I would say that’s my favorite of her films.

EZ: Me too. But the reason I bring that up in context to what you said is because there’s this way where the connection to the dirt and the land and the material and the aging of that house, and that Carolee lived there … I don’t know, it’s almost as if you could imagine women for hundreds of years pouring water and sweeping the porch, and everyone was important but forgotten because of society.

LS: Oh, I love the way you put that, yeah. Kitch’s Last [Meal] is a film that you watch and you just want to scream with excitement. I just can’t believe what an energizing experience that is. And the double screen. … It’s just absolutely brilliant.

EZ: I was thinking about it when you were speaking earlier about your film that you made with your boyfriend at the time and the multi-views and thinking about Fuses. There’s one part in Kitch’s Last Meal where she and Anthony [McCall, Schneemann’s partner during the making of the film] are walking in the snow and they switch camera views. So you see him, you see her, and it just has this timeless, ageless quality of two people in love walking in the snow. [It] is just perfectly captured.

LS: I wrote something on Kitch’s Last [Meal]. I feel like I should look for it, but anyway. I just love the split screen and the dynamics between very precise texture and daily life. And I love that it’s supposed … to have slippage, where different things happen. I mean, I know there exists a file where they’re together now, right?

EZ: Mm-hmm.

LS: But originally it was shown as two projectors, I believe. Did you know that?

EZ: Yeah. Did you see it in that format?

LS: I think I’ve only seen it as a digital version.

EZ: The digital. Me too.

LS: But I can’t sit here and just recollect images. Can I just read something that I wrote? … [Reading from letter Sachs wrote to Carlos Kase] “Just a little over a year ago, you graciously sent me ‘Art, Life, and Quotidiana in the Observational Cinema of Carolee Schneemann,’ your Millennium Film Journal essay on Carolee’s Kitch’s Last Meal. I noticed in your text that you refer to CS as Schneemann and that is, of course, the right thing to do. But since she was a dear friend, I need to refer to her in a more personal way. I know that you too had a relationship with her, so I think you will understand, especially since what I’m writing here is not public. Watching this film was cataclysmic, spiritual, ecstatic for me. I was able to see it online during the Rosendale tribute to her work.” Do you know what I’m talking about?

There’s a woman who did a whole [referring to Women in Experiment: Carolee Schneemann and Barbara Hammer, a film presentation at the Rosendale Theatre organized by Pam Kray, 2021]. … Anyway, [continues reading] “I assumed at the time that I’d seen it before. Maybe I had not, because I emerged proverbially–since I was at home of course–a different, slightly better human being. Reading your text was as close to being inside the film as I can think that I could ever be. I’m so taken with your precise eye, your willingness to allow. … This gave me a chance to think about the treatises she was offering us, which worked in contrast to the intimate domestic energy. Your article is a journey that runs so close to the film that it’s scary in the best of ways. You treat it as the time-based experience that it is. I happened to have read the 1953 panel discussion on the poetic in cinema, which included Maya Deren, Willard Maas, Arthur Miller, Dylan Thomas and Parker Tyler. Those guys just didn’t get it when Deren spoke about the vertical experience in non-narrative film. I think that having Schneemann there to pontificate with all the others would have done just the trick. Plus, her film breaks all expectations and is also kind of architecturally vertical as well.”

EZ: And that’s when you saw that film [referring to the presentation at Rosendale Theatre]? I had seen the film right before that. Actually Rachel [Helm], the manager of the Schneemann Foundation, played it for me in Carolee’s studio on an iMac after Carolee had died. It was a while after. I was sitting in her studio, second floor in the house, watching it on her computer.

LS: Oh, nice.

EZ: And I just thought, “Wow, this is really special.”

LS: I bet you had the shivers.

EZ: I did, because, you know, at a certain point when you see her working in her studio and things that are happening in that film, I would look and say, “Is that that door”? You know what I mean? That’s one of the experiences for me that comes through in her photography work and her artist’s books, but her film work also. …

LS: I think that Carolee let us feel excited about getting in front of the camera and getting behind the camera. Not doing it as an actor, but doing it in this tactile way that you were so present in the act of making something and you didn’t know where it was going to go. You just followed that journey. It’s the opposite of, in film, this notion of planning all the time. That’s how cinema works. That you execute something that comes out of a paper planner and she was just … this idea that you’re always present, just very present in the possibility of change. I love that.

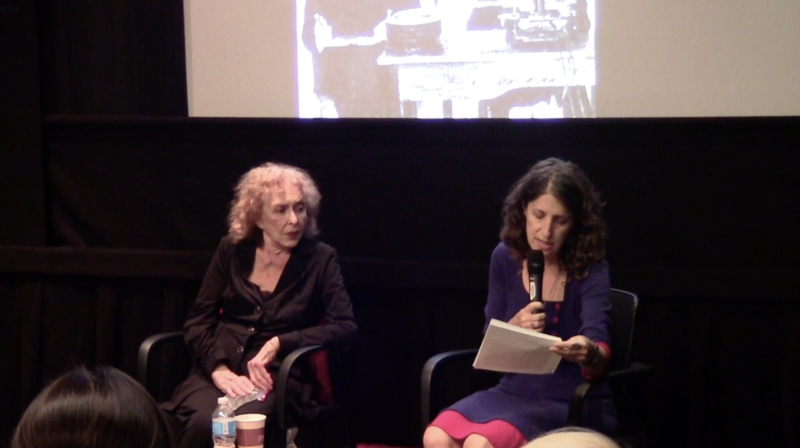

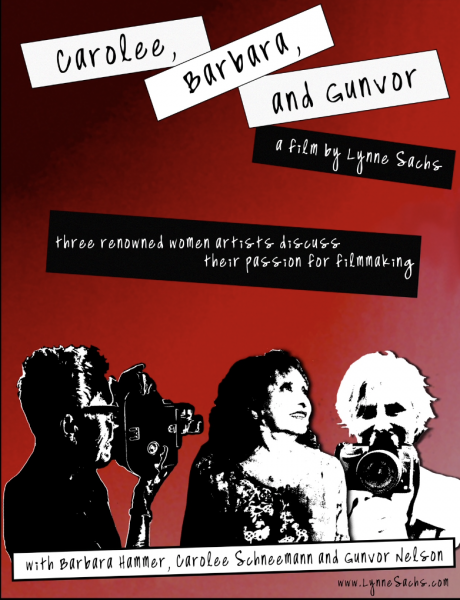

EZ: Let’s go ahead and jump to your film. Carolee, Barbara and Gunvor. I’d like for you to talk about that.

LS: Sure. As I was saying earlier, I think one of the great things about filmmaking is being responsive to a moment and being in a moment. … So with that in mind, I never said “I’m going to make a film about three great women artists.” I just knew that it was nourishing for me and interesting and inspiring to spend time with artists whose work I deeply admire, but also whose process and immersion in their own investigations was so specific. I just wanted to spend time with Carolee. I just wanted to spend time with Barbara Hammer and I just wanted to spend time with Gunvor Nelson. And I took a camera because I knew it was a vital and special experience that I was having. But then I was actually involved in a performance installation presentation at Microscope Gallery, and at the time they were in Brooklyn, so I just put all the three films together. And I said, “that would be kind of interesting.” And in a sense it was like the opposite of how films are usually made about famous people, because usually it has to have this, you know, [taking on an authoritative tone] a famous biopic, and this is the story and this is how you get to know whoever it is better. But I didn’t pretend to think that what I had done was going to tell you an enormous amount about any one of these artists. What I did think was that they were all living in the world at the same time and all extremely focused and driven … and that the camera was always a muse and also a challenge for them.

LS: I shot all the footage over a period of a couple of years. And then I said, “Oh, I’m going to make this movie. I better go talk to them.” And by that point, both Carolee and Barbara were not well, and we all thought that Barbara Hammer was less well, but Barbara was much more public about her illness than Carolee was. As you probably know, they died within a month of each other [Schneemann died on March 6, 2019 and Hammer died on March 16, 2019]. They had very different approaches to illness. That’s not in the film, but I will say that Carolee was more alternative about the medical system and more suspicious of it, and Barbara went through chemotherapy three times. I think they both wanted to live, but they wanted to deal with the institution of the medical system in different ways. Also, Barbara Hammer was much more political and forthright about the fact that when she wanted to die, she wanted to die, and she wanted it to be her own choice. And Carolee was much more hidden and sort of protective about that, you know.

EZ: Why do you think that is?

LS: That’s a good question. It’s interesting. Of the three women who are in the film, Barbara and Carolee were much more public people in the world than Gunvor Nelson was. And to my surprise, Barbara became extremely well recognized later in her life. There’s something happening now in the art world: like, “Let’s recognize older women artists.” I have another friend who’s in her early eighties and she said, “Lynne, I should have given you more paintings 20 years ago, because now they’re selling off the easel.” There’s a wonderful recognition, but also why is this happening? Is it being monetized too much by collectors? Let’s look at the invisible women and make them visible again–I’m definitely suspicious of that. And it’s interesting because both Barbara and Carolee painted [and] painting ultimately will always make more money than filmmaking … this kind of filmmaking. If you can sell a painting, you can get a different level of recognition in the marketplace, and the films will never have that. They both wanted recognition for their work that would give them more financial stability. And, you know, Barbara painted a lot. You probably don’t even know that.

EZ: No.

LS: She had gallery shows within the last ten years. Several. With hundreds of paintings. I actually didn’t realize that either. And I didn’t realize how important painting was to Carolee until the PS1 show. I think it was heartbreaking for both of them and also a wallet breaker that they didn’t sell more paintings. [Carolee would] say I’m a painter and I use a camera also. … I don’t think she ever said I’m a filmmaker.

EZ: No, I think if she was referred to as one, she would correct the person.

LS: And say, “I’m an artist.”

EZ: Or a painter.

LS: A painter.

EZ: And I think that [she saw] all of her work through the lens of “this is a painting.”

LS: Yes! I agree with you.

EZ: I do think that was something that was important to her. And I wonder if her decision to go through illness and even death in a more quiet way has something to do with those other ways in which she didn’t want to become these archetypes … not wanting to be identified as a dying artist who wasn’t recognized, and that becomes what you’re remembered for. Having control over that narrative.

LS: I’m just guessing that it was somewhat, probably quite disconcerting, all the focus on, [Interior] Scroll [1975] which she had done as a young woman. Every time she spoke, that piece would be discussed and so much of her more recent work wasn’t written about as much. That was upsetting.

EZ: I agree with you. It’s an important piece, and it becomes more amazing the more you know about all of her other work.

LS: Yes.

EZ: But on its own it’s easy to remember. You know, that’s one thing that when I try to tell someone about Carolee, something about her work, I say, “You know this artist. She did this.” … And you know that only, but now let’s talk about the other things.

LS: I don’t even know who took that photograph, but it is fantastic.

EZ: Anthony McCall did. He took the ones that are the most famous. But she did that performance [in 1975 and 1977]. Is there anything else about your film, about the experience that you’d want to have [on record]?

LS: I’ll just say, sometimes you just cannot predict how much work that you make, especially in collaboration with an artist, can transform your own life. That I’m having this experience, I think, is more because of the film than because I knew her–because there was a way that that film places her with her peers and gives you a sense of Carolee as a feminist but also as a woman of that generation. What they were discovering together, you know. She was so supportive of the film, as was Barbara, as was Gunvor, because I think they felt like their arms were locked together, like [they were] marching together. When I showed it at the Museum of Modern Art, Carolee came and we all went out with my daughter, with Kathy Brew [artist and videomaker]. We all went out. And Barbara. I’m trying to remember exactly. Together, for a 9-minute film, but we are all in that same space together and that was meaningful to me, and validating for my own relationships with other artists.

I guess I’d say that the gifts that Carolee gave to other artists as a friend were always so critical … so essential. And they weren’t ever as a mentor, and I think that’s a really important distinction–that she wanted to have comrades of all ages and experiences who were working with passion. She saw herself as an equal, even though she had this lifetime of experience. I guess I would say she’s a role model for me in that way because I’m 61 and young men and women, but maybe more women, write to me. And you could say, “Oh, I don’t have time to talk to them,” but I really do my best because I learn from them and it also gets me excited about continuing the process. Even teaching, for her, I could tell was exciting. She didn’t necessarily want to teach in this sort of strictly scholarly way where she created … you know, I never saw a syllabus. I wasn’t a student of hers, but I think she liked imparting her thoughts and looking at work by younger artists. I think that’s really vital to me, and I hope I can do the same.

EZ: That’s amazing. I think that’s a great way to end, because people becoming acquainted with her work and who she was as a person through these types of stories. I think that everything that you just said says a lot about who she was as a person, as well as within the framework of her work. … And I think she always liked trying out new things and making mistakes.

LS: [Do] you know the piece Flange [2011]?

Read more about this artwork

EZ: Huh-uh.

LS: The sculptural piece that looks like a wing–some sort of Greek sculpture of a bird or an armature, a human armature that moves. It’s kinetic, that sculpture, but it has a very raw feeling to it. I think that when you were in her studio, you’d see something like that and you’d go “Oh, I had no idea that she was creating kinetic sculptures that were very much not female.” I mean, that’s another thing. She had so much work that wasn’t strictly exploring women’s bodies. And I think she would have felt that we were narrowing her if that was all that history gave her. That’s why, in some ways, I feel it’s problematic to say, “Oh, she was a great feminist performance artist, conceptual painter, thinker.” She is a feminist, but it didn’t define everything. Or maybe the point is to expand what is feminism, so that you’re not just looking at the canon. Which she knew very well.