“Prime Time Reverie”

Curated by Aaditya Aggarwal

Canyon Cinema Discovered Programs

September 27, 2022

https://canyoncinema.com/2022/05/03/announcing-the-canyon-cinema-discovered-programs/

“The Televisual Woman’s Hour”

Essay by Aaditya Aggarwal

In what is now widely regarded as the world’s first public demonstration of television, a human face could not be fully transmitted. In 1926, Scottish inventor John Logie Baird came close, visualizing a ventriloquist’s cartoonish dummy named “Stooky Bill” with the help of radio technology. This puppet-like caricature presented stark enough contrasts in color required, at the time, to transmit an image.

Over the years, the television began to capture figures, faces, and objects with sharper clarity. During the 1920s, film laboratories started to photograph stock models to better calibrate desired exposure and color balance of black-andwhite film reels. In the essay “The China Girl on the Margins of Film,” Genevieve Yue describes the use of the inappropriately named “China Girl” in Western countries as a figure used as a color tone “next to color swatches and patches of white, gray, and black.”1 She was almost always unknown, young, female, conventionally attractive, and contrary to the name’s racial connotations, white. Never screened on film or television, her likeness offered engineers a so-called normative “skin-tone” to mute and elevate contrasts for film, so that the white face could be better visualized on screen.

It wasn’t until the 1940s that a televised woman could be perceived in full color. Post-World War II, TV became widely popular across homes and businesses in North America and the United Kingdom. In 1940, Baird began working on creating a fully electronic color television system called Telechrome. This system revealed an image that veered between cyan and magenta tones, within which a reasonable range of colors could be visualized. By the mid 1960s, this television box set began to depict an even wider range of colors. A growing influx of pinks, purples, yellows, and greens in our home screens began to shape newer practices of looking.

Frequently sighted on analog televisions was a rainbow screen, formally known as SMPTE color bars. A testing pattern employed by video engineers, this arrangement compared and recalibrated a televised image to the National Television System Committee’s (NTSC) accepted standard. Often used in tandem with images of the China Girl, SMPTE bars were typically presented at 75% intensity, setting a television monitor or receiver to reproduce chrominance (color) and luminance (brightness) correctly. Its vertical bars—positioned in the screen from left to right, in white, yellow, cyan, green, magenta, red, and blue—were often accompanied by a high-pitched tone.

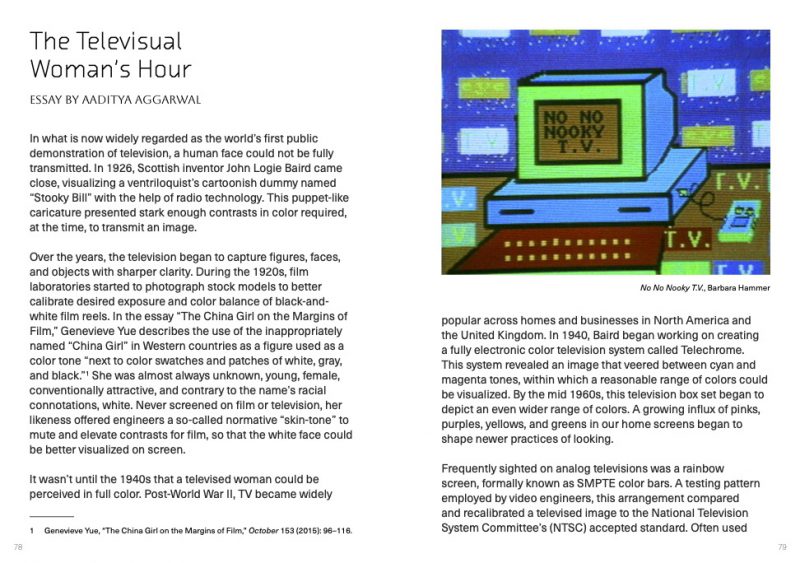

Enabling more sophisticated, accurate, and textured imagery, this new color television began to usher a distinctly erotic encounter between the appliance and its viewer. From the early 1970s onwards, with the arrival of subscription-based cable networks like HBO, soft-core porn became a staple of private viewing. In her video work No No Nooky T.V. (1987), Barbara Hammer references this genre of late-night, often pay-perview programming, deconstructing its portrayals of female pleasure and physicality. Lensing an Amiga computer with her 16mm Bolex, the artist stages and contorts the alphabet with sensual and cryptic animation. A remix of patterns, shapes, and letters accompanies a sterile, computerized voiceover: “By appropriating me, the women will have a voice.”

Reappropriating pornographic language, No No Nooky T.V. reflects on the tactility of the television. One glimpses a TV in bondage, wrapped in black cloth and white twine. Later, it is clasped in multiple bras. Typed into a computer, one message reads: “Does she like me? WANT ME? DESIRE ME? KILL FOR ME? LUST FOR ME?” Another artfully scribbles “dirty pictures” in bejeweled cursive. There is a hilarity in Hammer’s harnessing of a screen in this material way, made absurd by technoincantations of text littered in different fonts.

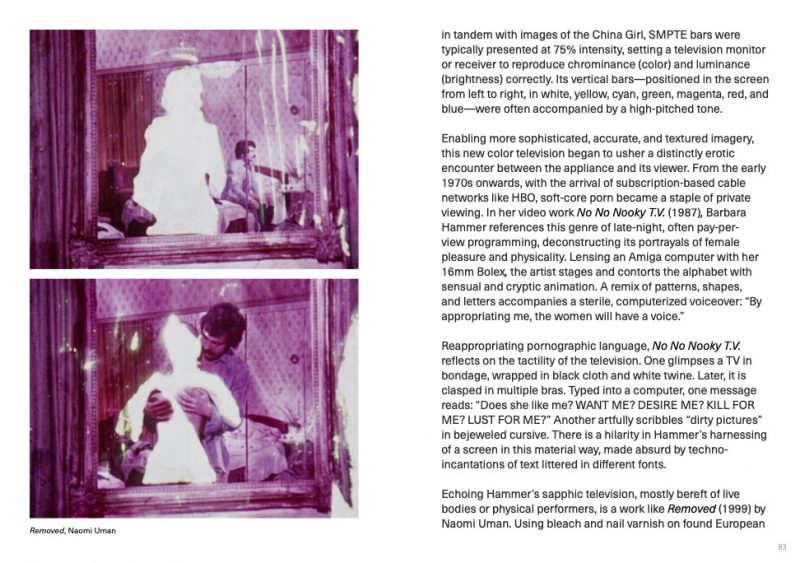

Echoing Hammer’s sapphic television, mostly bereft of live bodies or physical performers, is a work like Removed (1999) by Naomi Uman. Using bleach and nail varnish on found European porn films from the 1970s, Uman selectively erases and manually empties out physical bodies of actresses. Whitened, unrecognizable female silhouettes clash against magenta-tinted bedroom surroundings, depicting the televised woman as an open, blank, animated space.

The artist’s removal of the corporeal feminine starkly contrasts against color television’s historic hypervisibility of women’s bodies. Typifying the latter is a work like Nam June Paik and Jud Yalkut’s Waiting for Commercials (1966- 72), where a montage of found Japanese commercials from the 1960s is populated by gleeful stock performers, mostly composed of young women. Inhabiting the screen in between programs, female models in ad breaks market a range of products—from Pepsi-Cola to cosmetics to apparels. In Paik and Yalkut’s selection, the televised woman bursts as an object of curiosity for her viewers; albeit in heightened artifice, her joy of selling drink or dress is unparalleled.

Intrigued by representations of femininity and desire, Waiting for Commercials evidences the ubiquity of the televised corporeal feminine; one that Removed visually effaces or that No No Nooky T.V. only teases with mere glimpses—sing-song figures, euphoric, ecstatic, enthralled by touch, excited by commodity These works engage multiple figurations of the “televised woman,” a conception that continually structures and stages a viewer’s sense of tedium, anticipation, and disclosure.

—

When I approach the history of television, the appliance reveals itself as a predominantly women’s medium. From cosmetic commercials to exclusive interviews to narrative melodrama, women’s television—or television catered specifically to female viewers—is formally diverse, nudging and mirroring its spectators in intimate and discerning ways. Of its many subgenres, one that offers its viewers both entertaining and pedagogical conceptions of womanhood is the soap opera. Whether it is the exaggerated intensity in plot twists of Days of our Lives (1965-present) or the moral polarity of female characterization in Dynasty (1981-89), soap operas instill in us a measure of persistent expectation. In her essay “The Search for Tomorrow in Today’s Soap Operas: Notes on a Feminine Narrative Form,” Tania Modleski emphasizes a soap’s tendency to inevitably return towards anticipation. She notes: “Soap operas invest exquisite pleasure in the central condition of a woman’s life: waiting—whether for her phone to ring, for the baby to take its nap, or for the family to be reunited shortly after the day’s final soap opera has left its family still struggling against dissolution.”

2 In its most effective moments, a soap avoids narrative resolution to unrealistic ends. Dramatizing traditional ideas of motherhood and wifehood, soap protagonists and antagonists continually revert to domestic cliffhangers. In a scene from Days of Our Lives, for example, a slyly dainty and theatrically erudite Alexis Colby (played by a breathy, extravagant Joan Collins) makes eye contact with her ex-husband’s current wife. The camera zooms in on Alexis, the antagonist, as her eyebrow arches and head tilts in quiet disdain and alerted defense. Seesawing between seduction and virtuosity, soap characters surprise each other with turns of phrase. And while each episode oscillates between familial bliss and disorder, a soap never ends.

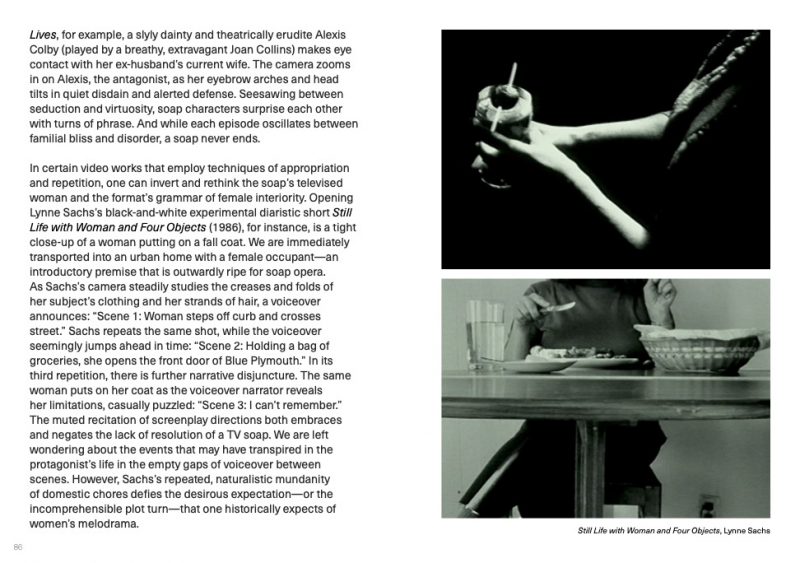

In certain video works that employ techniques of appropriation and repetition, one can invert and rethink the soap’s televised woman and the format’s grammar of female interiority. Opening Lynne Sachs’s black-and-white experimental diaristic short Still Life with Woman and Four Objects (1986), for instance, is a tight close-up of a woman putting on a fall coat. We are immediately transported into an urban home with a female occupant—an introductory premise that is outwardly ripe for soap opera. As Sachs’s camera steadily studies the creases and folds of her subject’s clothing and her strands of hair, a voiceover announces: “Scene 1: Woman steps off curb and crosses street.” Sachs repeats the same shot, while the voiceover seemingly jumps ahead in time: “Scene 2: Holding a bag of groceries, she opens the front door of Blue Plymouth.” In its third repetition, there is further narrative disjuncture. The same woman puts on her coat as the voiceover narrator reveals her limitations, casually puzzled: “Scene 3: I can’t remember.” The muted recitation of screenplay directions both embraces and negates the lack of resolution of a TV soap. We are left wondering about the events that may have transpired in the protagonist’s life in the empty gaps of voiceover between scenes. However, Sachs’s repeated, naturalistic mundanity of domestic chores defies the desirous expectation—or the incomprehensible plot turn—that one historically expects of women’s melodrama.

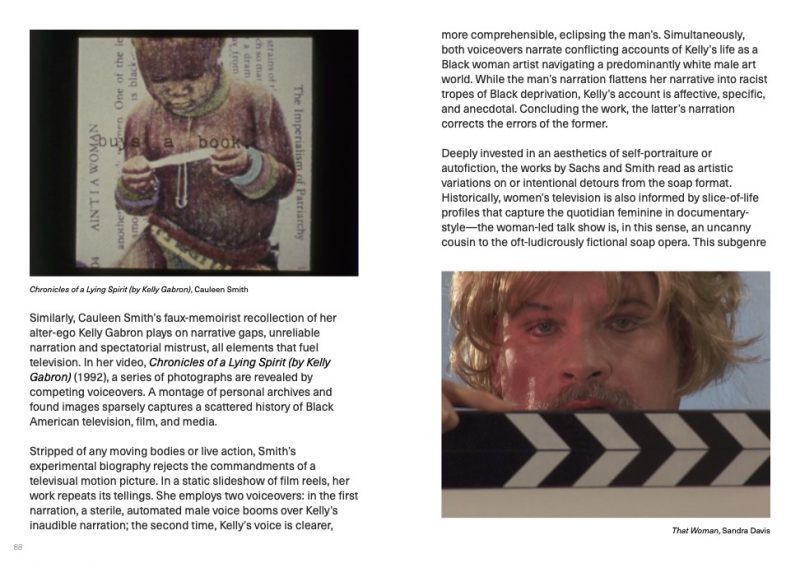

Similarly, Cauleen Smith’s faux-memoirist recollection of her alter-ego Kelly Gabron plays on narrative gaps, unreliable narration and spectatorial mistrust, all elements that fuel television. In her video, Chronicles of a Lying Spirit (by Kelly Gabron) (1992), a series of photographs are revealed by competing voiceovers. A montage of personal archives and found images sparsely captures a scattered history of Black American television, film, and media.

Stripped of any moving bodies or live action, Smith’s experimental biography rejects the commandments of a televisual motion picture. In a static slideshow of film reels, her work repeats its tellings. She employs two voiceovers: in the first narration, a sterile, automated male voice booms over Kelly’s inaudible narration; the second time, Kelly’s voice is clearer, more comprehensible, eclipsing the man’s. Simultaneously, both voiceovers narrate conflicting accounts of Kelly’s life as a Black woman artist navigating a predominantly white male art world. While the man’s narration flattens her narrative into racist tropes of Black deprivation, Kelly’s account is affective, specific, and anecdotal. Concluding the work, the latter’s narration corrects the errors of the former. Deeply invested in an aesthetics of self-portraiture or autofiction, the works by Sachs and Smith read as artistic variations on or intentional detours from the soap format. Historically, women’s television is also informed by slice-of-life profiles that capture the quotidian feminine in documentary style—the woman-led talk show is, in this sense, an uncanny cousin to the oft-ludicrously fictional soap opera. This subgenre of programming arguably originated from scripted sketchbased programs like the Lucille Ball-led I Love Lucy (1951-57) as well as daytime reality-based shows like The Loretta Young Show (1953-61) and The Betty White Show (1952-54). From BBC’s Woman’s Hour (1946-present) to the French program Dim Dam Dom (1965-73), dramatized stories of real-life female figures often blended with interview-based programs. A female presenter, in turn, became a hyper-televised woman. Her success relied on her performance as a triple-threat in roles of cultural commentator, comedian, and confidante. In solo interviews, journalists like Barbara Walters adroitly shifted or affirmed national narratives, oftentimes muddying their newsworthy interviewees’ vulnerable reputations.

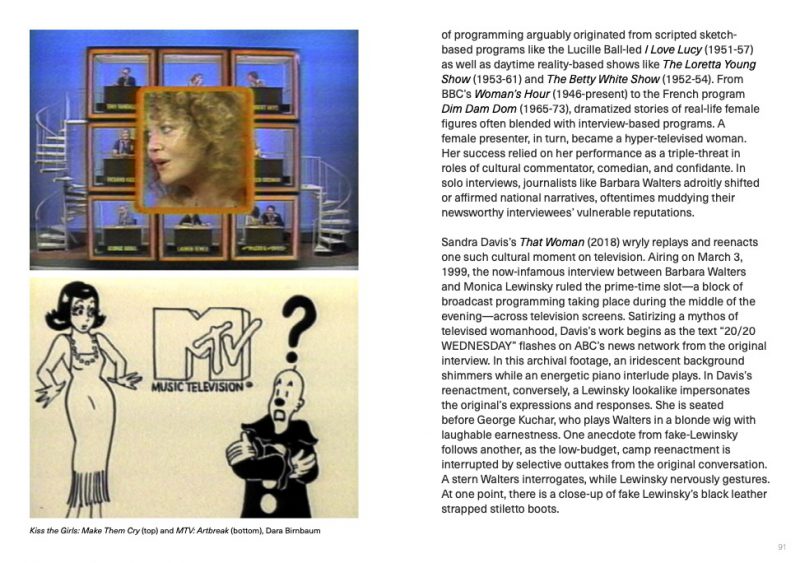

Sandra Davis’s That Woman (2018) wryly replays and reenacts one such cultural moment on television. Airing on March 3, 1999, the now-infamous interview between Barbara Walters and Monica Lewinsky ruled the prime-time slot—a block of broadcast programming taking place during the middle of the evening—across television screens. Satirizing a mythos of televised womanhood, Davis’s work begins as the text “20/20 WEDNESDAY” flashes on ABC’s news network from the original interview. In this archival footage, an iridescent background shimmers while an energetic piano interlude plays. In Davis’s reenactment, conversely, a Lewinsky lookalike impersonates the original’s expressions and responses. She is seated before George Kuchar, who plays Walters in a blonde wig with laughable earnestness. One anecdote from fake-Lewinsky follows another, as the low-budget, camp reenactment is interrupted by selective outtakes from the original conversation. A stern Walters interrogates, while Lewinsky nervously gestures. At one point, there is a close-up of fake Lewinsky’s black leather strapped stiletto boots.

Davis’s reappraisal of this episode captures the coercive candor and pronounced intensity of appointment television, where primetime interviews oddly invoke the narrative melodrama of soap opera. For instance, much like the soap heroine, a talk show’s subject is also activated by the zoom-in, a technique frequently employed in sensationalist news telecasts and scandalous journalistic exposes.

Writing on the invention of the close-up in silent film, Béla Balázs describes its “intimate emotional significance” and “lyrical charm” in Theory of the Film, recalling “audience panic” at the first sight of a close-up of a smiling face in a movie theater.3 The format of a televisual soap furthers Balázs’s argument of a close-up’s ability to reveal “unconscious expressions,” in discomfitingly proximate confines, scanning a poreless, powdered face. In moving close-up, the televised woman spans the expanse of a screen, intimating what Rawiya Kameir describes as the “pointed drama” of a zoom-in in her 2016 review of Solange’s A Seat at the Table. “Moments later,” she writes, “the world beyond her falls away…”4

A zoomed-in figure becomes as solitary as a television box set, her presence both disarmingly novel and routinely domestic. But what are the limits of her close-up? Does the televised woman ever exit our saturated screens? Emily Chao’s hermetic close-up in her black-and-white work No Land (2019) comes to mind. Over the course of two minutes, she zooms into a square-shaped, TV-like black sheet pinned on a tree trunk, surrounded by wild, dense forestry. Invoking the early invention of analog screens, one is unable to visualize any corporeal form or countenance in its frame; the transmitter of images instead becomes the image itself, bearing a haptic imprint of its televisual women—invisibilized stock model, adorned brand ambassador, exalted porn star, scheming soap vamp, jovial female presenter, overexposed subject—always visible in the interiors of your living room.

Edited by Girish Shambu

______________

1 Genevieve Yue, “The China Girl on the Margins of Film,” October 153 (2015): 96–116.

2 Tania Modleski, “The Search for Tomorrow in Today’s Soap Operas: Notes on a Feminine Narrative Form,” Film Quarterly 33, no. 1 (1979): 12–21.

3 Béla Balázs, Theory of the Film: Character and Growth of a New Art, trans. Edith Bone (Dover Publications, 1970). 4 Rawiya Kameir, “Solange, In Focus,” The Fader, Oct. 6, 2016, https://www.thefader. com/2016/10/06/solange-a-seat-at-the-table-essay.

4 Rawiya Kameir, “Solange, In Focus,” The Fader, Oct. 6, 2016, https://www.thefader. com/2016/10/06/solange-a-seat-at-the-table-essay.