Essay on Cinema Guild’s DVD & Bluray monograph insert for Film About a Father Who directed by Lynne Sachs

Information on the DVD & Bluray here.

“He knows he will live in me

Sharon Olds, from the book of poems, The Father

after he is dead, I will carry him like a mother.

I do not know if I will ever deliver.”

There are so many possible entry points into Lynne Sachs’s A Film About a Father Who, an incredibly poignant and astute film sonnet on the director’s father, Ira Nathan Sachs, that over my repeated viewings I’ve begun to think of the film as a kind of quilt. Each of its patches unique and carefully hand-stitched into the fabric of its mosaic parts. Or perhaps a wondrous maze that a viewer winds her way through, and out, by pulling a delicate Ariadne’s thread.

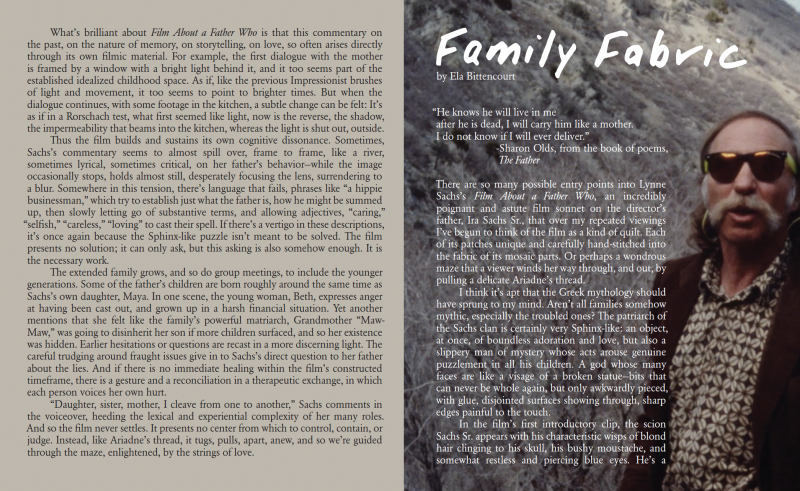

I think it’s apt that the Greek mythology should have sprung to my mind. Aren’t all families somehow mythic, especially the troubled ones? The patriarch of the Sachs clan is certainly very Sphinx-like: an object, at once, of boundless adoration and love, but also a slippery man of mystery whose acts arouse genuine puzzlement in all his children. A god whose many faces are like a visage of a broken statue — bits that can never be whole again, but only awkwardly pieced, with glue, disjointed surfaces showing through, sharp edges painful to the touch.

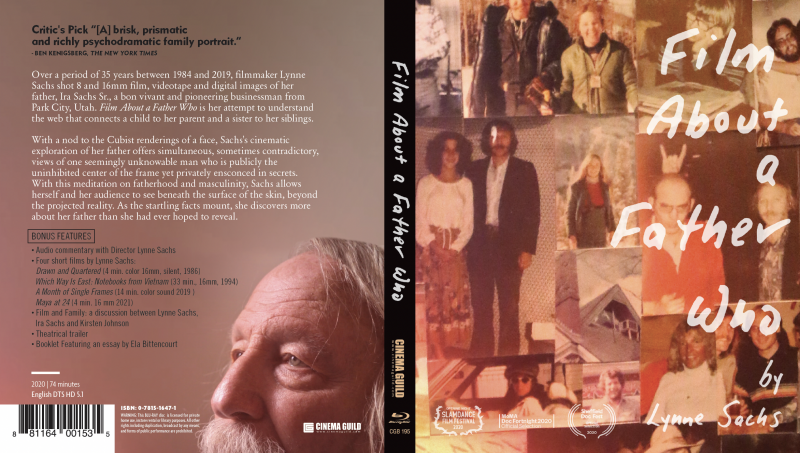

In the film’s first introductory clip, the scionSachs, Sr. appears with his characteristic wisps of blond hair clinging to his skull, his bushy moustache, and somewhat restless and piercing blue eyes. He’s a “hippie businessman,” who “works as little as possible,” and “bottles water he can never stock.” In one shot, he stands framed by a mountainous vista (it turns out that Sachs developed hotels in Park City, Utah, where the Sundance Film Festival is held). The father speaks of his love for skiing, where you “go up slow and come down fast.” A comment that Sachs comments on in her own presciently clipped way: “To own a mountain from which there is nothing you can do but come down.”

I was struck by how this sentence is a gorgeous metaphor for pretty much how we relate to our parents — the most primordial love, which turns them into heroic, mythical, statue-like beings, mountain slopes from which, indeed, they can only come down. And how much of growing into adulthood is about the sudden vertigo of having to rewind, recalibrate our memories of the familial bind, from the times when we were still too innocent, too small, to have truly understood it. If we love them enough, we catch them coming down. We are mindful to pick up the pieces, glimpsing in their downfall from immortal heights the first sightings of our own fragility.

A Film About a Father Who is then an origin story, but one that’s never smug about its certainties, and always self-doubtful of how “it all” began. Sachs opens the film with a scene in which she’s cutting her elderly father’s hair, a moment so low-key yet so potent, because it is non-verbal. Everything else in the film – the tale of how the father managed to lie and cheat for so many years, how he hid his multiple affairs and his many children by different women from each other, for decades – all this will need to be explained. But the hair-cutting, with Sachs holding the scissors, untangling the knots, so that to snip them, lives outside language, time, it is an act of generosity and love, through which a small portion of care may me given back. Then there’s the scissors, which once again circle back to the metaphor of quilting, cutting things to pieces, and stitching them together — film editing itself like quilting, the kind of hands-on experimental cinema that Sachs practices, in particular, like the intricate, patient, artisanal task.

Sachs begins her story with the immediate family nucleus, her father, mother and her siblings, Dana and the filmmaker Ira Sachs. In this first central patch, there is still a certain sense of cohesion, as if the rest of the film could shoulder the illusion of producing a unified body of work; as if the process of delving into the past could heal, through rendering the small patches whole. Nothing like this occurs, it turns out. The more there is to discover, the more women and children enter the picture, the more quilt-like the film’s overall composition becomes. It demands to be seen as unruly, with each person, each story and heartache, finding its own proper place.

Among the father’s lovers are Diana, whose faint voice betrays terrible shyness, both on the subject’s part, but perhaps also the filmmaker’s. The inherent question of how to probe without hurting, how to make space for learning and empathy, but also establish a critical distance, is always keenly felt. Over the course of the film, this empathetic investigation becomes emboldened — either reflecting the director’s natural progression, or perhaps a mere artifact of thoughtful, painstaking editing, through which each woman’s testimony enriches the others. With Diana, for example, Sachs plants the idea of “companionship,” which apparently Sachs’s father used to seduce the young immigrant, Diana. And yet, Diana’s profile, cast against a dim window, is so lonely, so desolate, the word gains a heartbreaking, bitterly ironic twang.

If, as Tolstoy believed, all happy families are alike, but the unhappy ones suffer in distinct ways, Sachs’s film is indeed an epic that embodies a Tolstoian ethos. “I’ve been making this film about my father for twenty-six years now,” Sachs says at one point. In another she adds, “Can I make myself forget that for the first twenty years of my sister’s life I didn’t know of her existence?”

It’s a challenge to tell a story of such breadth without giving in to the tyranny of summary. But Sachs is never guilty of it, perhaps because, from the start, she strikes a patient but also an ironic tone. She holds out each cesura and is never rushed. Her carefully planted voiceovers, which echo, like refrains, emphasize dissonance, slippage, and paradox—as if to borrow Emily Dickinson’s motto, “Tell the truth, but tell it slant.” It’s a particularly poignant approach to a subject who is himself quite unable to offer this level of complete honesty, or transparency. We might have grown frustrated with such a subject, as too illusive, too coy, and yet, when centered in and filtered through Sachs’s voice, her father’s slipperiness becomes part of the game, a psychological, moral, philosophical quest for a glimmer of comprehension, and solace.

Again and again, this filmic richness emerges, where the previous parts of the film serve as a commentary on what comes next. Take the early family videos, for example. There is so much light, the children bouncing about, the colors overexposed, pushed, which on one hand reminds us of the fragility of earlier technologies, but on the other, doesn’t let us forget that family videos are a particular brand of narrative—or, one might say, fantasy. One makes a family. One constructs a memory. The film contains these small patches of idealized moments, frozen in time, it holds them in, like quilted patches, but it can also reveal them as such.

What’s brilliant about A Film About a Father Who is that this commentary on the past, on the nature of memory, on storytelling, on love, so often arises directly through its own filmic material. For example, the first dialogue with the mother is framed by a window with a bright light behind it, and it too seems part of the established idealized childhood space. As if the previous Impressionist brushes of light and movement, it too seems to point to brighter times. But when the dialogue continues, with some footage in the kitchen, a subtle change can be felt: It’s as if in a Rorschach test, what first seemed like light, now is the reverse, the shadow, the impermeability that beams into the kitchen, whereas the light is shut out, outside.

Thus the film builds and sustains its own cognitive dissonance. Sometimes, Sachs’s commentary seems to almost spill over, frame to frame, like a river, sometimes lyrical, sometimes critical, on her father’s behavior—while the image occasionally stops, holds almost still, desperately focusing the lens, surrendering to a blur. Somewhere in this tension, there’s language that fails, phrases like “a hippie businessman,” which try to establish just what the father is, how he might be summed up, then slowly letting go of substantive terms, and allowing adjectives, “caring,” “selfish,” “careless,” “loving” to cast their spell. If there’s a vertigo in these descriptions, it’s once again because the Sphinx-like puzzle isn’t meant to be solved. The film presents no solution; it can only ask, but this asking is also somehow enough. It is the necessary work.

The extended family grows, and so do group meetings, to include the younger generations. Some of the father’s children are born roughly around the same time as Sachs’s own daughter, Maya. In one scene, the young woman, Beth, expresses anger at having been cast out, and grown up in a harsh financial situation. Yet another mentions that she felt like the family’s powerful matriarch, Grandmother “Maw-Maw,” was going to disinherit her son, if more children surfaced, and so her existence was hidden. Earlier hesitations or questions are recast in a more discerning light. The careful trudging around fraught issues give in to Sachs’s direct question to her father about the lies. And if there is no immediate healing within the film’s constructed timeframe, there is a gesture and a reconciliation in a therapeutic exchange, in which each person voices her own hurt.

“Daughter, sister, mother, I cleave from one to another,” Sachs comments in the voiceover, heeding the lexical and experiential complexity of her many roles. And so the film never settles. It presents no center from which to control, contain, or judge. Instead, like Ariadne’s thread, it tugs, pulls, apart, anew, and so we’re guided the maze, enlightened, by the strings of love.

About Ela Bittencourt

Ela Bittencourt is a critic and cultural journalist, currently based in São Paulo. She writes on art, film and literature, often in the context of social issues and politics.