A Hard Act to Follow: A Daughter’s Cinematic Reckoning with Her Father

By Lynne Sachs

With editing advice by Alexandra Hidalgo

July 8, 2022

I’ve been making experimental documentary films since the late 1980s, beginning with Sermons and Sacred Pictures (1989) all the way through to Film About a Father Who (2020)—a total of 37 films, ranging in time from 90 seconds to 83 minutes. Over the years, I have made non-fiction and hybrid works that continue to shift my point of view from shooting from the outside in, to shooting from the inside out. That is to say, I make a few films that allow me to “open the window” on a person, group of people or place that I know little about in order to develop a deeper understanding or answer a gnawing question through my filmmaking. Then, I turn the camera back on myself and my immediate surroundings to produce more personal, introspective films. This back and forth positioning is a critical pivot that is fundamental to my own commitment to working with reality. I can only ask the people who allow me to witness all the vulnerable manifestations of their lives to enter my filmic cosmos if I too have gone to a similarly exposed place myself.

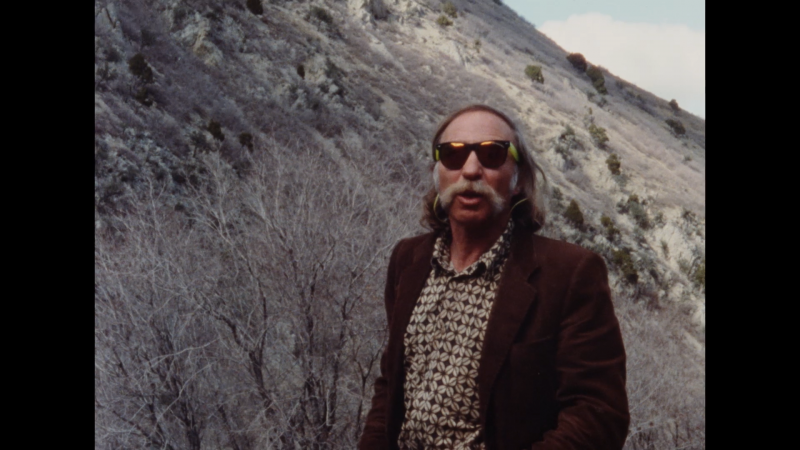

Still from” Film About a Father Who”.

Lynne Sachs learning to swim, 1965. Photo by Ira Sachs.

Film About a Father Who is my cinematic reckoning with my father Ira Sachs, a bohemian entrepreneur living in the mountains of Utah. In making this film, I forced myself to follow this sometimes daunting edict. Together shooting my images and writing my narration made me come to terms with what I had always concealed and what I needed to reveal. In order to bring the film to life for you, my readers, I have added what I uttered in the film’s narration whenever it blends in a generative fashion with what I’m discussing.

Every Thursday was Bob Dylan day. Dad didn’t care about the lyrics or the harmony, only the melody. He was a hippy businessman, buying land so steep you couldn’t build, bottling mineral water he couldn’t put on the shelves, using other people’s money to develop hotels named for flowers. He worked from a shoe box, and as little as possible.

Still from” Film About a Father Who”.

Lynne Sachs with her father, sister Dana and brother Ira, Jr. in Memphis, 1965. Photo by Diane Sachs.

Born in 1936 in Memphis, Tennessee, my father has always chosen the alternative path in life, a path that has brought unpredictable adventures, multiple children with multiple women, brushes with the police and a life-long interest in trying to do some good in the world.

He did not define himself by his work, but rather what he did the rest of the time, like drifting down a mountain or devouring the news and doing what you do to make children, who happen to become adults.

To own a mountain from which there is nothing you can do but come down, nowhere to build. What happens when you own a horizon?

Shooting from the Inside Out

My film takes a look at the complex dynamics that conspire to create a family. There is nothing really nuclear about all of us, we are a solar system composed of nine planets revolving around a single sun, a sun that nourishes, a sun that burns, a sun that each of us knows is good and bad for us. We accept and celebrate, somehow, the consequences. In 1991, when I was thirty years old, I decided that the best way for me to come to terms with my relationship with my father would be to witness his life, to record my interactions with him and his interactions with the rest of my family and perhaps the world.

Still from” Film About a Father Who”.

Ira Sachs with daughters Lynne and Annabelle Sachs in San Francisco, 1991.

I’ve never quite known where the “inside’ is with my father. Over the decades, I’ve organized many recorded interviews—a time, a place, and a structure so that he would feel it was the right moment to tell me where he lives when he is alone—driving in his car, looking out from his living-room window at the Wasatch range, listening to the quiet of an evening snowstorm. My father speaks more intimately of the trees and the steep slopes that reach up around him than he does of his closest human companions. He swears to me that he does not dream, so in “real life” he conjured his own fantastical situations.

Dad had twin Cadillac convertibles. He didn’t want his mother to know he was so extravagant, so he painted them both red. He could pull up in either one and she would never know the difference. For a long time, neither did I.

The first time I saw both cars parked together, I was shocked that he had two. It was his secret, but now I was also keeping it.

He had his own language and we were expected to speak it. I loved him so much that I agreed to his syntax, his set of rules.

Rather than admit his propensity for buying one new toy after another, my father did whatever he felt like doing and assumed we, his children, would be there to support him. We were good kids, so we participated knowingly in all the shenanigans that made his world spin the way he wanted it to spin.

Still from” Film About a Father Who”.

Ira Sachs in Oakland, California, 1991. Photo by Lynne Sachs.

Never in all the years of making this film did my father find an ease with speaking about or even acknowledging his convulsive, peripatetic childhood. That past is a country he left behind. For most of my adult life, I’ve been familiar with the obvious facts and people—his mother, high school, jobs, children—but I honestly could not figure out how these scattered events came together to become my father. The mature, rational “me” whispered: “You don’t have the right or the need to put all of the pieces together. Let him stand on the present. The details of his past are not critical to your life.” Each and every time that I flew from my home in Brooklyn, New York to his home in Park City, Utah, or that he visited me, I filmed. As a result, I had hours and hours of material on 8mm and 16mm film, video, and digital that I needed to climb my way through.

How the Camera Witnesses our Changing Bodies

Still, I was scared to do this. What would I find? How could I crack his, and thus our, finely constructed amnesia? Watching our old movies during the editing process, I sometimes missed the people we were, or caught a glimpse of a man I pretended to know, but somehow didn’t. There is something so apt about the expression “Hindsight is 20/20.” The more I forged my way forward in time, the more I learned about my father’s compartmentalized life, Slowly, I began to realize that what I needed to articulate were the fissures, the images that I would never be able to capture because he was performing a complicated life on so many stages at once, and I was only privy to a few of them.

While my “subject” was growing older, his skin taking on new wrinkles and folds, much of the technology I was using to record our lives would change completely every few years. Over the course of my three-decade “production” period, I shot 16 mm film, using the same Bolex camera I purchased in 1987 for $400. But, I also relied upon an evolving array of video tape and digital formats. Indeed, Film about a Father Who includes an archeological palimpsest of 20th and 21st Century technologies, including: VHS camcorders; Nagra 1⁄4” audio tape records; HI-8; mini-DV; Digital Single Lens Reflex and Osmo cameras; Zoom digital recorders; and, cell phones.

Still from” Film About a Father Who”.

Lynne Sachs on road trip across the country, 1989. Photo by Lynne Sachs.

My camera witnessed. My microphone recorded. No matter which apparatus I held, I always knew that nothing was really what it seemed.

When I was 24, I took a trip with Dad and my sister Dana to Bali, where he had invested in a small hotel. This was supposed to be the first time when would have his complete attention. One afternoon, Dad took us on a drive. Like so many times during our childhood, we had no idea where we were going or why. We arrived at the airport and from the car window we saw a very young woman, a girl, walk out of the terminal. We were so hurt, so infuriated that we immediately got on a bus and went to the other side of the island, only returning in time for our flight home. As it turned out, she was not just another weekend date whose name we would never even learn. This was Diana [my father’s very young girlfriend who eventually became his second wife]. It took me six years to seek out her perspective.

Making this film forced me to come to terms with those images that gave me aesthetic pleasure and those images that I called “ugly” but somehow conveyed a new level of meaning. At the beginning of my logging process, I dismissed much of the of the older tapes, particularly the ones that my father had shot on his consumer grade VHS camera. They were too sloppy or degraded by time and the elements, be they hot or cold. Later, with my editor Rebecca Shapass at my side, we revisited this material and realized that these off-the-cuff images offered us a critical opportunity to see the world through my father’s eyes. If Dad was not going to reveal his understanding of the world via a more typical documentary-style interview, I would have to rely on this material to understand his point of view. With the Bali footage, for example, you can hear slivers of conversation between my dad and me shot at night as he happened to be staring up at the moon. When you listen carefully to our words, you pick up the aural texture of our relationship in a way that more image-centered material would not reveal. This discovery actually pushed me to go back to all of my outtakes, to scavenge amongst the disregarded NG (no-good) bins in search of the unfiltered sounds from my past. I could hear raw kindnesses, assertive admonitions, and subtle avoidance that were, in a sense, more natural and certainly more haunting.

I was born in the 1960s as were my sister Dana and my brother Ira. By the time I was 10 years old, my parents were divorced. In 1985, my father began what I’ll call a series of other family scenarios, with a new wife, and lots of girlfriends—both simultaneously and consecutively. There was no point in trying to keep count and initially I had no documentation of these other lives my father was leading. By 1995, I had four new siblings; and by 2015, we became aware that there were two more secret sisters. I was already in the thick of making Film About a Father Who (I even had the title), but I had to find a way to shape my narrative to allow for all of these new, significant people.

Still from” Film About a Father Who”.

Ira Sachs, Sr. with girl friends in Park City, Utah, 2005. Photo by Ira Sachs, Jr.

Pushing Myself to See Beyond the Surface

I decided to seek out each of my siblings (beginning with my sister Dana born in 1962 and ending with my youngest sister Madison, born in 1995) and three of six of their mothers (including my own), knowing that the only way I could construct a group portrait of our father would be to include my five sisters and three brothers. From the beginning, I was inspired by German author Heinrich Boll’s 1971 polyvocal novel Group Portrait with Lady, in which a narrator interviews 60 people in order to better understand one woman. With a nod to Picasso’s Cubist renderings of a face, my exploration of my father embraced 12 simultaneous, sometimes contradictory, views of one seemingly unknowable man who is publicly the uninhibited center of the frame yet privately ensconced in secrets. I hoped that my film could ultimately see beyond the surface, beyond the persona our father had constructed, his projected reality.

In the fall of 2017, I hired two professional camera people and a sound recordist to join me on the day before Thanksgiving at my brother Ira’s apartment in New York City for the first-ever gathering of all my siblings. While everything else in the film had been shot by someone in the family, I hoped that this formal “set up” would produce an anchor for the narrative, an opportunity for all of us to get to know each other better and to reveal our feelings about our father and his evolving family. We shot for four hours, and the experience was, for the most part, cathartic. But, as I looked through the footage with my editor, I noticed that everyone was extremely aware of how I, in particular, responded to their words. Even a quiet sigh or a subtle raising of an eyebrow seemed to indicate to them what I was thinking. This, I believe, is a common scenario in documentary filmmaking, one that mirrors the dramatic paradigm in which actors look to directors for an affirmation that they have done a good job. It took me a year to accept that this singular, more contrived, scene was significant in terms of who was there in the same room, but did not take the film to the place I needed it to go.

Still from” Film About a Father Who”.

Lynne Sachs in conversation with newly discovered sister Julia Sachs, 2018.

Photo by Rebecca Shapass.

And so, throughout the following year, I either flew my siblings to Brooklyn or went to meet them where they lived. In almost every case, I convinced my sisters and brothers to go into a completely darkened space with me. We often sat in closets. It was weird and very intimate. As I recorded their voices, resonating through my headphones, I knew I was listening to them in a deeper way than I had ever done before. There in the dark, they each accessed something new about our father that they had never articulated before.

We’re pretty candid about who Dad is and we’ve seen him through a lot, but we’re also able to shift what we might recognize as who he really is to what we want him to be.

Still from” Film About a Father Who”.

Ira Sachs, 2018. Photo by Rebecca Shapass.

My father’s life was clearly going to be a “hard act to follow.” Yes, I had felt empowered to shoot with him for this protracted period of time, but every time I sat down to look at my footage something would get in my way. I would tell myself that all the material was so poorly shot there just wasn’t enough to make a movie. Or I was too busy teaching, or taking care of my children, or anything else that came to my mind. Ultimately, what I think stopped me each time was fear of the story I wanted to tell. Finally, I as a daughter and a filmmaker, I realized that I needed to work with a person who could help me muddle through half a century of material. Never in my entire career as a filmmaker have I hired a professional editor to work with me on a film. Instead, I either cut my movie myself or invite former students (or students of former students) to join me on this post-production phase of a project. In 2017, I invited Rebecca Shapass, a marvelous undergraduate student from a class on avant-garde film, to work with me as my studio assistant. At the time, Rebecca was 22 years old, exactly the same age as I had been when I started shooting my “Dad Film” (as my family referred to it). Within just a few months, I realized Rebecca was the perfect person to collaborate on my project. Her profound empathy, her patience, and her sophisticated aesthetic sensibility made for the perfect combination of qualities I needed in an editor who could help me log, transcribe and shape all of my material.

Finding My Voice

Still, one of the biggest and most intimidating aspects of making this film would be finding a way to translate my own interior thoughts—be they loving, rage-filled, compassionate or simply contradictory—about our father into a convincing, not too self-conscious, voiceover narration.

As we moved from being girls to women, my sister and I shared a rage we never knew how to name.

From the very beginning, I knew that Film About a Father Who would be an essay film that would include my own writing. One of the reasons the film took so long to make was that every time I sat down to put a pen to paper, I became intimidated by the process. I felt embarrassed by my anger, apologetic about my embarrassment, and frustrated by my awkward inability to accept the whole range of emotions I wanted to express. I also had no idea how to shape my newly discovered periods of bliss and confidence that I had found with my father, especially since I had given birth to my own daughters and was more insightful about the challenges of being a parent.

In January 2019, I had a three-week artist residency at Yaddo in Saratoga Springs, New York. In my application, I explained that I had been working on one personal essay film, dare I say it, for most of my life, but that I needed a quiet, somewhat isolated place to write down my thoughts. I guess Yaddo thought it was a worthy endeavor, as they invited me to join about 12 other artists during that time. Lucky for me, I suppose, this was a particularly icy period in Upstate New York; taking long walks in the woods, as I had expected to do each day, was so risky that it was prohibited. I had no excuse but to write. For the first few days of the residency, I diligently placed my notebook on my empty desk, opened it to the first available page, pulled out my lovely fountain pen (which I hoped would inspire eloquence) and eventually wrote down a few words. Next, I read the words—usually around 20 at most—over and over again. Then, I would scratch them out and start again. At least, I thought to myself, I am not using a computer where the delete button beckons, seduces, and devours. There were still traces of dwindling assertions and quotidian doubts.

After a few days of anguished horror vacui, I realized that this conventional, familiar way of writing was never going to work, at least for this film. As if like a flash of light, or a jolt of electricity, it dawned on me that I had other tools available that might help me to generate the words for which I was so desperately looking. At around 4:30 p.m., just as my dwelling in the woods was starting to get dark, I unpacked my Zoom audio recorder, put on my headphones, closed all the doors to remind myself that I had absolute privacy, plopped myself on my bed with a bunch of pillows, and began to speak into the microphone. At first, it felt awkward and humiliating, so there in the dark I decided to make myself feel even more alone. I closed my eyes and let go. I am a person who is, more often than not, consistently self-aware and polite. I say what I mean, but I sometimes cover up how I really feel with an acute attention to grammar and kindness. Now, in this funky isolation, this makeshift recording studio, this anything-goes-at-last sensation of solitude, I let loose and the words poured out. Over a period of 10 days, I recorded hours of material—oral histories, in a sense—that were generated by me as daughter, artist, and director. To my surprise, I was actually able to apply the newly discovered “in the dark” approach to recording with my siblings to the way that I listened to my own thoughts.

When I began transcribing the words I had spoken, I found the task both painful and laborious. Speaking these candid words pushed me to my limit, into another zone of introspection. Then it occurred to me that in this high-tech, service-oriented world in which we all live, I could solve this problem quite easily. I sent my audio files to a transcription service and within 36 hours a typed document file of an inchoate narration arrived in my email inbox. I spent the second half of my residency reading and editing my own words, almost as if they had been created by someone else. There, before me, almost magically, but then again not, was the skeleton for my film, the narration.

I actually believe that my enthusiasm for recording in the dark is an outgrowth of the current image-crazy culture in which we live. Each of us, in our own way, attempts to cultivate and control the various forms of media that feign to mirror who we are. By turning out the lights, we can begin to go beyond and below the epidermal, eventually connecting with and releasing our inner thoughts.

Unlike the rest of the world, one of the qualities that most intrigues me about my father is his total disregard for how he looks on camera. Throughout our shooting together over many years, he never thought one way or another about what he was wearing, whether or not his hair was brushed, or who was in the frame with him. At first this aspect of his personality convinced me that he was going to be an easy subject of documentary study. Only later did I realize that in order to “get into his head” I needed to see the world from his point of view.

Still from” Film About a Father Who”.

Ira Sachs photographing family in Park City, 1991. Photo by Lynne Sachs

Seeing the World Through My Father’s Eyes

In the late ‘80’s and ‘90s, Dad carried a video camera around with him all of the time. After about a year editing together in my studio, Rebecca and I realized that we needed to take a closer look at these images to get into my dad’s head in a deeper way. With this frame of reference in mind, we found two pivotal images that ultimately became key visual metaphors for the entire film. The first image, which appears very early in the film and then continues later in two other places, is of three of my younger siblings playing in a stream bed on the side of a mountain property my father had recently purchased. It appears that the shot was produced with a tripod, as it is perfectly steady for the entire seven minutes. For me, it is sublime. I do not exaggerate. No doubt accidently, my father photographed what art historians would call the golden triangle of classical painting. As my two half-brothers and one half-sister play and pretend to carefully move a garden hose across some rocks, I can hear my father speaking to them with affection and cautious scolding. Even at a distance of about twenty feet, you can feel the parental intimacy, the children’s simultaneous desire to please and do exactly what they want. As if worn and tattered by the thirty years this tape spent on a shelf in my father’s garage, the footage has been reduced to three pastel colors. Now a mother myself, I can see how this image captures all of the love a parent can express for their children, here it is contained by the film frame and the raw aura of the setting.

Still from” Film About a Father Who”.

Quarry explosion outside Park City, Utah, circa 1990. Photo by Ira Sachs, Sr.

In one other initially disregarded image, I found the essence of my father’s relationship to the natural landscape he both loves and yearns to control, even, dare I say it, exploit. This is short shot during which you watch the top of a mountain above a limestone quarry in the moments just before explosives are used to blow up the ground. You can hear my father in all of his excitement counting down the seconds before the highly anticipated event. In the same voice that another person might prepare for the lighting of candles on a child’s birthday cake, my father gathers his gaggle together to watch the transformation of a mountain side into sellable commodity. For me, the duality of the visual moment encapsulates so much of what makes my father the adventurous appreciator of all things natural and the clever business man who was always looking for something that might generate some cash.

To explain every ambiguous situation would be to dissolve the cadence of our rhythms. No balance, no scale, no grid, no convention, no standard aspect ratio, no birthplace, no years, no milestones. This is not a portrait. This is not a self-portrait. This is my reckoning with the conundrum of our asymmetry. A story both protracted and compressed. A story I share with my sisters and brothers, all nine of us. My father’s story…. Or at least part it.

Through an accumulation of facts coming together over time, I discovered more about my father than I had ever hoped to reveal. From this perspective, Film About a Father Who captures my naïveté transformed into awareness, my rage transformed into forgiveness. But, there is also another vantage point I can now better understand. As the mother of two adult daughters, I can see the way that my actions have left an imprint on their psyches, their sense of self and self-worth. I am steadfast in my own commitment to engaging with them in full transparency, admitting my mistakes, and taking them along for the long ride ahead. It may not have been by his example, but I did learn through my relationship with my father how important it is for a child to be brought into their parents’ lives as fully as possible.