“Thought, Word, Image: Introduction to Lynne Sachs Retrospective”

Costa Rica International Festival of Cinema, 2022

Written by Fernando Chaves Espiniche, Artistic Director

Translated from Spanish by Maria C. Scharron

There are films that seem small but on screen they expand until we are overwhelmed. That is what happens with the images and words that Lynne Sachs pieces together: her films seem fragile, transparent, but they hit us with the force bestowed by the mind behind them.

Since the late 80s, this American artist has been building a group of work that expands and blurs the limits of fiction, documentary and the experimental expressions of cinema art. In more than 40 films, between feature films, short films, performances, web projects and installations, Sachs has demonstrated to be one of the most authentic voices of American experimental cinema. She provokes, challenges, and proposes. Her movies give the impression of simplicity, which the emotional and intellectual weight betrays. Even when the films are straightforward, they raise deep questions that make them expand beyond their short duration.

But, what does someone like Lynne Sachs have to say about the Costa Rican and Central American context? Although her movies are intimate, Sachs’ films speak about what we call universal themes: home, memory, time, family, and cinema as a device to inquire into everything. It is her modest scale, (and we already mentioned that this should not distract us from her incisive glance), which lead us to think about other ways to approach cinema as producers, critics and spectators. Something is burning in these images of Sachs’, something that motivates us to imagine another way of narrating: the drive to film everything, transforming it all with voice, editing, thought and rhythm.

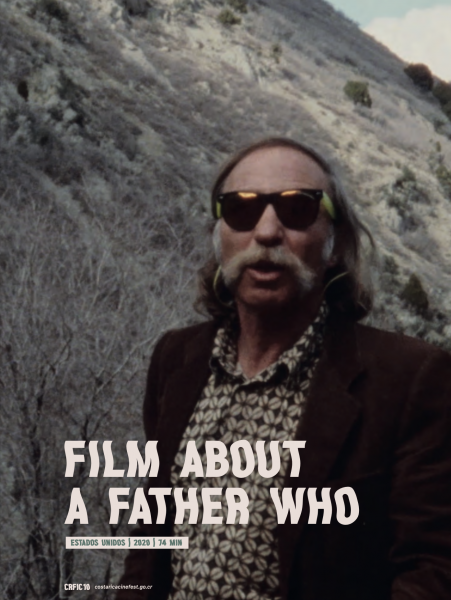

In Films About a Father Who (2020), which we had the pleasure to show in the 9th Cosa Rica International Festival de Cine, the director dissects her father’s presence with deep empathy and an objective eye. The debris of memory accumulates around a very complex figure. This challenges our understanding of him, but without leaving affection and tenderness behind. Personal history is made of small fragments recorded and filmed throughout the years, an accumulation of interactions and moments that reveal, even through their apparent banality, a compromise with the world and its inhabitants. By putting them together and letting the editing do its work and make them speak, these fragments expose other truths, they open fissures to other intimacies.

Sachs also sketches these family portraits through gestures: in Maya at 24 (2020), her daughter runs around her at ages 6, 16 and 24. Filmed in 16mm, it fuses the emotional landscapes of each age –ages, by the way, that are crucial in a woman’s life–, letting herself be surrounded by love and energy. Lynne is at the center of this gesture: this act also touches and affects her.

We also have to talk about the material nature of film itself, which brings us closer to, we could say, the manual process of transforming those images into a narrative-poem-gesture that summons us and invites us to get involved with these lives. The passage of time is inscribed in these films; the film is affected by light, movement, time and manipulation. Even in digital films we can still feel the presence of the artist’s touch, which is key. Sachs’ works are an invitation to dive deep into the vast archive of images and sounds that we generate, not only to dig into our childhood or hidden stories, but to find ourselves in the process.

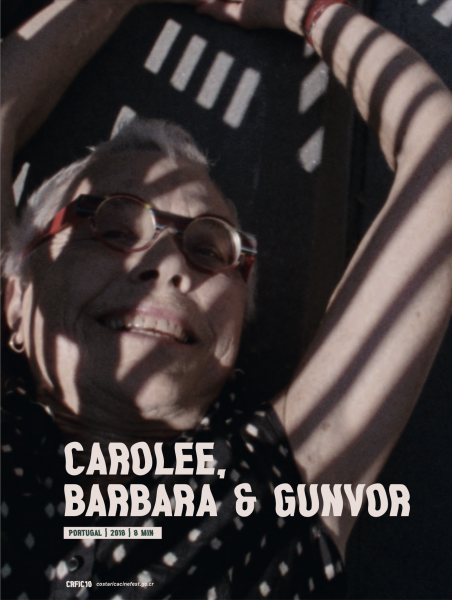

It’s weird. With Sachs’ films, we end up feeling like we already know her, that we have talked to her for hours and hours. As in any conversation, one topic leads to another, images repeat, ideas come and go. But as every word turns, another angle reveals itself. In this sense, the power of the minimum inscribes Sachs’ work in a long history of women who have used the moving image as a tool to find themselves, to transform their bodies and their environments and register the beat of a century that learned to see itself through cinema. In Carolee, Barbara and Gunvor (2018), we witness the visits Lynne made to the pioneers of experimental cinema: Carolee Schneeman, Barbara Hammer, and Gunvor Nelson. Visits to the places they called home. They speak about their body and their body of work. They share pieces of their thoughts so we can participate in a different way with their films. Lynne Sachs’ films are an exercise in memory, an expanding memory. From the minimal to the immense, from gesture to revelation. Like glimpses, her movies invite us to be part of a poem: we are just another verse that rhymes with changes of direction, scattered dialogues, the movement of objects and the cuts that link moments that without Lynne’s diligent gaze we would never have found. At CRFIC we are thrilled to present this cinema of what is possible, of what is close. We want to converse with Lynne and her films, and we are fortunate she has opened that door for us.

Translated from the Spanish Original by Maria C. Scharron

“Pensamiento, palabra, imagen” de Fernando Chaves Espinach

Director Artístico, Costa Rica Festival International de Cine

Existe cierta clase de cine que parece pequeño pero que, en la pantalla, se expande hasta abrumarnos. Así sucede con las imágenes y palabras que hilvana Lynne Sachs: parecen películas frágiles, transparentes, pero nos golpean con la contundencia que les confiere el profundo pensamiento que las genera. Desde finales de los años 80, esta cineasta estadounidense ha estado construyendo una obra que expande y confunde los límites de la ficción, el documental y las expresiones experimentales del arte cinematográfico. En más de 40 películas, entre largometrajes y cortometrajes, así como performances, proyectos web e instalaciones, Sachs ha demostrado ser una de las voces más auténticas del cine estadounidense experimental. Provoca, desafía y propone. Sus películas aparentan una sencillez que su carga emocional e intelectual traiciona; incluso cuando son directas, plantean hondas preguntas que las expanden más allá de su breve duración.

Pero, ¿qué dice alguien como Lynne Sachs a un contexto como el costarricense y centroamericano? Incluso cuando son íntimas, las películas de Sachs hablan de lo que llamamos temas “universales”: la casa, la memoria, el tiempo, la familia y el cine como dispositivo para indagar en todo aquello. Asimismo, es en su modesta escala, que como ya hemos dicho, no debe distraer de su incisiva mirada, que nos mueve a pensar otras formas de acercarnos al cine como realizadores, críticos y espectadores. Algo arde en estas imágenes de Sachs que nos impulsa a imaginarnos otra forma de contar: es la voluntad de filmarlo todo y transformarlo con la voz, la edición, el pensamiento, el ritmo.

En Film About a Father Who (2020), que tuvimosel placer de mostrar en el 9CRFIC, la directoradisecciona la figura de su padre con profundaempatía y una mirada objetiva. Los escombros dela memoria se acumulan en torno a una figuracompleja que nos reta a comprenderlo, sin dejarde lado los momentos de cariño. La historia personalse conforma de pequeños fragmentos grabadosy filmados a lo largo de los años, una acumulaciónde interacciones e instantes que revelan, apesar de su aparente banalidad, un compromisocon el mundo y con sus habitantes. Al unirlos ydejar que la edición les permita hablar en conjunto,los fragmentos emanan otras verdades, abrengrietas a otras intimidades.

Sachs también esboza estos retratos familiarespor medio de los gestos: en Maya at 24 (2020), suhija corre a su alrededor a los 6, 16 y 24 años,filmada en 16mm, fusionando los paisajes emocionalesde cada edad –edades, por otra parte,cruciales en la vida de una mujer–, dejándoserodear por su amor y su energía. Lynne está en elcentro de ese gesto: el acto la trastoca a ellatambién.

Hay que hablar también de la materialidad del filme mismo, que nos aproxima al proceso manual, diríamos, de transformar estas imágenes en una narrativa-poema-gesto que nos convoca y nos invita a inmiscuirnos en estas vidas. En las películas está inscrito el paso del tiempo; la cinta se deja afectar por la luz, el movimiento, las horas y la manipulación. También en lo digital se nota esta “mano de la artista”, que es clave. La obra de Sachs es una invitación a hundir las manos en el vasto archivo de imágenes y sonidos que generamos, no solo para excavar momentos de nuestra niñez o historias ocultas, sino para encontrarnos en ellas.

Es raro. Con el cine de Lynne Sachs uno siente quela conoce, que ha conversado con ella por largashoras. Como en cualquier charla así, un tema llevaa otro, se repiten imágenes, ideas van y vienen.Pero en cada giro de la palabra, se devela otroángulo posible. En ese sentido, ese poder de lomínimo inscribe la obra de Sachs en una historiaextensa de mujeres que han tomado la imagen enmovimiento como herramienta para encontrarse,transformar su cuerpo y su entorno, y registrar elpulso de un siglo que aprendió a mirarse en el cine. En Carolee, Barbara and Gunvor (2018), vemoslas visitas que Lynne hizo a Carolee Schneeman,Barbara Hammer y Gunvor Nelson, pioneras delcine experimental, en los lugares que han llamadohogar. Hablan de su cuerpo y de su obra. Noscomparten algunas piezas de su pensamientopara que participemos de otro modo en sus películas.

Así, el cine de Lynne Sachs es un ejercicio dememoria, de una memoria que se expande. De lomínimo a lo inmenso, del gesto a la revelación.Como en destellos, sus películas nos invitan aformar parte de un poema: somos un verso más,que rima con los giros, los diálogos sueltos, elmovimiento de los objetos y los cortes que unenmomentos que, sin la mirada acuciosa de Lynne,jamás se hubieran encontrado. En el CRFIC nosilusiona presentar este cine de lo posible y de locercano. Queremos conversar con Lynne y susfilmes, y para nuestra dicha, nos ha abierto lapuerta.

“Thought, Word, Image”

by Fernando Chaves Espinach

Artistic Director, Costa Rica International Film Festival