Jonas Mekas died yesterday, but with this close to a full, feisty and mostly extraordinarily fun life, he leaves us all with so much. From an early age, Jonas came to understand that living the life of an artist to the very fullest meant that you were expected to create something that would last beyond your last breath. Before anyone was really using the word “community”, Jonas was building a formidable infrastructure that would be the very foundation for the survival of the personal cinema he loved so dearly. Jonas made hundreds of short, improvisational movie poems with his family, his friends, various celebrities, waiters he met, people on the street, anybody and everybody. But his commitment to cinema only began with his art making. Jonas worried so much about what would happen to these films after they tumbled out of his and everyone else’s cameras. His concern quickly turned to careful, methodical and brilliantly conceived action in the early 1960s when he founded two absolutely critical sister organizations: Anthology Film Archives, which screens all ranges of alternative, international, underground film seven days a week; and, the Film-makers’ Cooperative which distributes a collection of 5000 works of cinema. How grateful we all are to Jonas Mekas for his vision and commitment to creating these two organizations, partners in the simple crime of cinema.

Jonas Mekas died yesterday, but with this close to a full, feisty and mostly extraordinarily fun life, he leaves us all with so much. From an early age, Jonas came to understand that living the life of an artist to the very fullest meant that you were expected to create something that would last beyond your last breath. Before anyone was really using the word “community”, Jonas was building a formidable infrastructure that would be the very foundation for the survival of the personal cinema he loved so dearly. Jonas made hundreds of short, improvisational movie poems with his family, his friends, various celebrities, waiters he met, people on the street, anybody and everybody. But his commitment to cinema only began with his art making. Jonas worried so much about what would happen to these films after they tumbled out of his and everyone else’s cameras. His concern quickly turned to careful, methodical and brilliantly conceived action in the early 1960s when he founded two absolutely critical sister organizations: Anthology Film Archives, which screens all ranges of alternative, international, underground film seven days a week; and, the Film-makers’ Cooperative which distributes a collection of 5000 works of cinema. How grateful we all are to Jonas Mekas for his vision and commitment to creating these two organizations, partners in the simple crime of cinema.

In 1994, my husband Mark Street and I moved from San Francisco to the Lower East Side for the summer. We found a tiny apartment a few doors down from Anthology Film Archives, on 2nd Street and thus began our love affair with each other and with the New York alternative film world. We would often run into Jonas on the street and he would either encourage us to come to a screening or chide us for missing a show we would have loved.

We remained in touch with Jonas over the many years, always able to find him in a crowd wearing his blue denim vintage Parisian sanitation worker jacket. A couple of years ago, I searched for months for a suitable replacement jacket, since he had told me his was wearing out. After much online research, I found a new/ old one and had it sent from France. I nervously presented it to Jonas at a public gathering where we were both speaking about the history of San Francisco’s Canyon Cinema, another sister to the Film-Makers’ Coop. Jonas nodded wisely and then responded with these words, “What I really needed were new pants.”

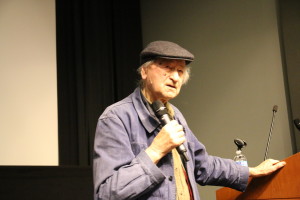

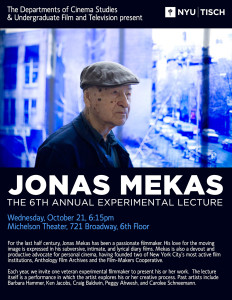

In 2015, I invited Jonas to present the 6th Annual Experimental Lecture in NYU’s Cinema Studies Department. We offered Jonas a ride to and from his home in Brooklyn, but he refused mightily, preferring to use public transportation with a friend whenever it was possible. No V.I.P. treatment for me, he huffed. At least 100 people crowded into the standing room only lecture hall and accompanying spill-over room. For three hours, Jonas gave a talk about all ranges of cinema, people he knew, films he made, wherever his thoughts took him … no notes, always precise, woven together like an exquisite braid.

In 2015, I invited Jonas to present the 6th Annual Experimental Lecture in NYU’s Cinema Studies Department. We offered Jonas a ride to and from his home in Brooklyn, but he refused mightily, preferring to use public transportation with a friend whenever it was possible. No V.I.P. treatment for me, he huffed. At least 100 people crowded into the standing room only lecture hall and accompanying spill-over room. For three hours, Jonas gave a talk about all ranges of cinema, people he knew, films he made, wherever his thoughts took him … no notes, always precise, woven together like an exquisite braid.

“I have a need to film small thing, almost invisible daily moments,” he often said. Last year, I attended Jonas’s lecture on small things at Microscope Gallery in Bushwick. The gallery was full once again. It was a glorious talk, one in which he donned a wolf mask on occasion and spoke of all ranges of intimate, distilled, tiny things in his life, in the world, in a gallery. No coincidence we were gathered in a place called Microscope. I remember he spoke rather critically of the new Whitney Museum, stating that he had told the director or even the board that they needed to exhibit more small things in small spaces. One administrator responded that they had plenty of small things in their collection. But that was not enough for Jonas. You need more small rooms, he said.

That night, I left the gallery, got in my car and started to drive home by myself. About a block away, someone knocked on the back, right window while I was stopped at an intersection. I looked over my shoulder, and there was Jonas with an enormous bouquet of flowers. I rolled down the window and asked him if he needed a ride home. He said yes, and so we drove away together. Throughout the drive I was nervous that I would have a wreck with my esteemed passenger in the back seat, imagining the headlines in the newspaper the next morning. But Jonas seemed very happy about the arrangement, asking me all about my daughters, my husband Mark, different films we’d both made, my plans for the future. He packed it in, and he cared. He cared about everything.

That night, I left the gallery, got in my car and started to drive home by myself. About a block away, someone knocked on the back, right window while I was stopped at an intersection. I looked over my shoulder, and there was Jonas with an enormous bouquet of flowers. I rolled down the window and asked him if he needed a ride home. He said yes, and so we drove away together. Throughout the drive I was nervous that I would have a wreck with my esteemed passenger in the back seat, imagining the headlines in the newspaper the next morning. But Jonas seemed very happy about the arrangement, asking me all about my daughters, my husband Mark, different films we’d both made, my plans for the future. He packed it in, and he cared. He cared about everything.