Portrait of the Artist as a Room by Lynne Sachs

On Studio: Remembering Chris Marker

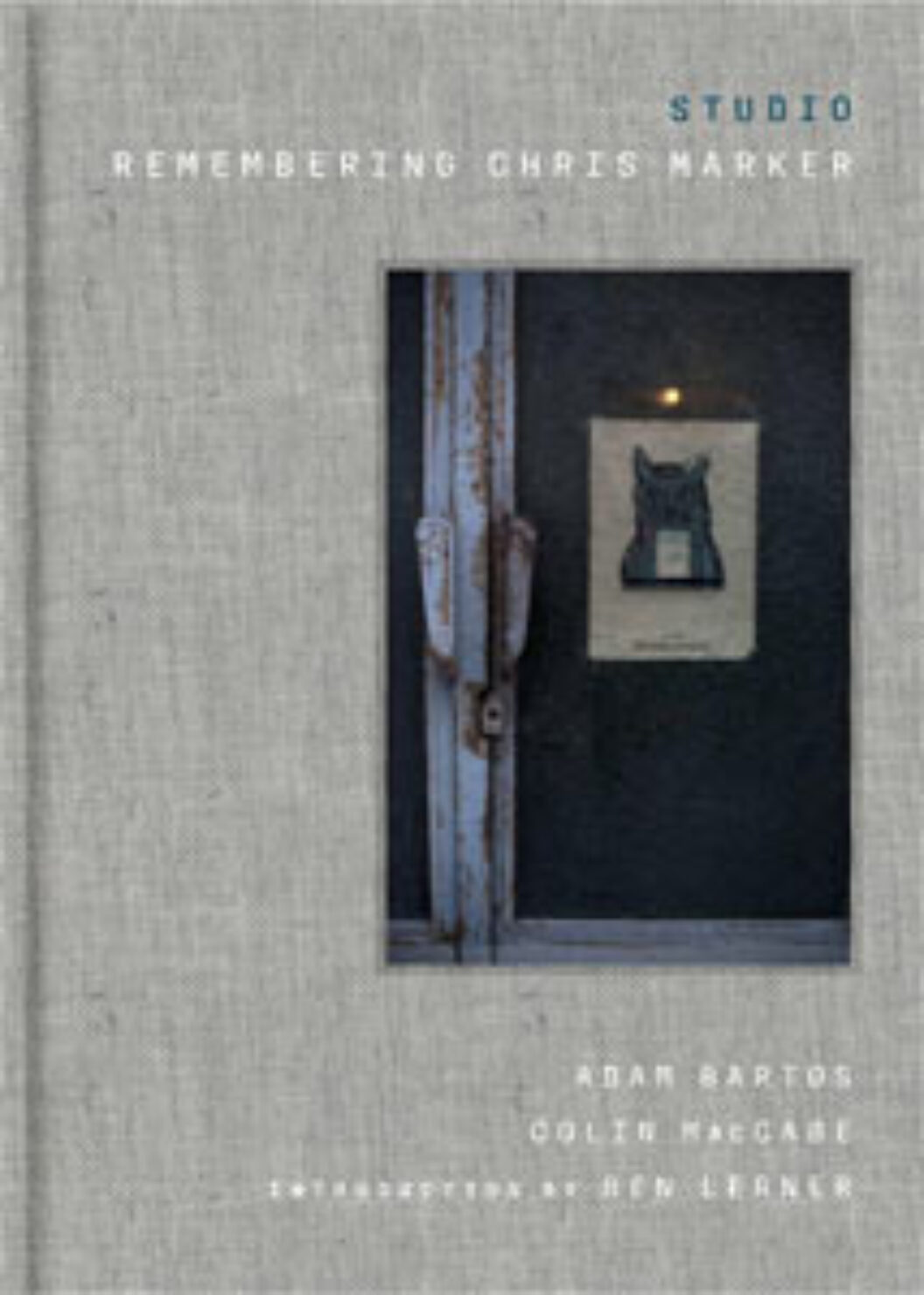

Chris Marker’s studio on the Rue Courat, Paris, April 4, 2007. Photo by Adam Bartos. Courtesy of the artist.

In San Francisco in the mid-1980s, I saw French filmmaker Chris Marker’s expansive, enigmatic ciné meditation Sans Soleil (1983). I witnessed his mode of daring, wandering filmmaking with a camera. Alone, he traveled to Japan, Sweden, and West Africa where he pondered revolution, shopping, family, and the gaze in a sweeping but intimate film essay that shook the thinking of more filmmakers than any film I know. Marker’s quasi-autobiographical movie blended an intense empathy with a global picaresque. It presented the possibility of merging cultural theory, politics, history, and poetry—all aspects of my own life I did not yet know how to bring together—into one artistic expression. I wrote my own interpretation of the film and then boldly, perhaps naively, sent it to Marker in Paris.

Several months later, his response arrived with a slew of cat drawings along the margins. Marker also suggested that we continue this conversation in person, in San Francisco. Not long afterward, I found myself driving Chris from his hotel in Berkeley to Cafe Trieste, one of the most famous cafes in North Beach. There we slowly sipped coffees in the last relic of 1960s hippy culture, talking about his films, his travels, and my dream to become a filmmaker. As the afternoon came to a close, I politely pulled out my camera and asked if I could take his picture. “No, no, I never allow that.” And then he turned and walked away, leaving me glum, embarrassed, and convinced that my new friendship with Marker was now over.

American film scholar Colin MacCabe struck up a similar friendship with Marker, one that began in 2002 with the transport of an obscure VHS tape from film enthusiast and producer Tom Luddy in Berkeley (once again) to Chris’s studio home in Paris. Over the next ten years, MacCabe would welcome any excuse for traveling from his home in Pittsburgh across the Atlantic Ocean to France. MacCabe’s longing was not for the food, wine, River Seine, or joie de vivre, but rather for the sheer pleasure of conversing about history, the dilemma of the twentieth century, cinema, technology, and the French actress Simone Signoret with Chris Marker. From the very first moment that MacCabe crossed the threshold into the lair of this quiet lion in the world of personal and political cinema, he knew it would change his life. The range and depth of topics these two men discussed is exhilarating. In reading MacCabe’s new short, anecdotal memoir, Studio: Remembering Chris Marker, we can easily glean that the passage of thoughts from-lip-to-ear-and-back-again between these two cerebral fellows left an indelible imprint on MacCabe. Marker’s place of creation, his home on the Rue Courat in a less-than-famous but spectacularly diverse neighborhood of Paris was a magnet for Macabe; he would travel there whenever possible, even if the two men’s tête-à-tête only lasted an hour. MacCabe explains that as revered as he was by filmmakers, essayists, poets, thinkers of any kind, Marker had two fundamental qualities: “a generosity of spirit and… a genius for friendship.” Having read many a text on Marker, never have I come across such an intimate, respectful recounting of his personal life. Little did I know, for example, that the highlight of his studies at the Sorbonne was working with Poetics of Spaceauthor Gaston Bachelard; that his admiration with the French Resistance network was grounded in his infatuation for its beautiful leader Marie-Madeleine Fourcard; or that “The experience of fighting as an American soldier, for which he received a personal letter of thanks from Eisenhower, meant that Marker could not countenance any of the knee-jerk anti-Americanism that so disfigures the thought of the European left.”

Both MacCabe’s and my communications with Chris evolved simultaneously. Chris made extraordinarily good use of the new epistolary canvas: email. I can only guess how many people around the world cherish such correspondence (most often with the subject heading News from Guillaume, Guillaume being his cat.) In 2007, I assisted Chris on the creation of an English version of Three Cheers for the Whale, his short 1972 film. There in the same loft apartment Adam Bartos so exquisitely photographed for Studio, we talked about everything from his friends Black Panther leader Eldridge Cleaver and American documentarian Robert Kramer to Russian films he’d pulled from the Internet, cats, and tea—themes he would explore deeply with MacCabe as they parsed through texts they each were writing or reading.

“It was one of Marker’s absolute principles that he could not appear in public alongside his works. It was an ultimate taboo. I have often surmised that it was linked to a fantasy of death— that were he and his work to appear together his death would ensue,” explains MacCabe. Marker’s aversion to being photographed was profound. Type his name into Google and the only pictures you will find are in black and white, an archeological tracing that probably ends in the 1960s. And so it is that we turn each delicately folded folio page in Studio to reveal the place where Chris Marker lived and collected and edited the media-based projects of the last decade of his life. Here, in all its ecstatic detail, we are able to take account of a visible manifestation of the artist’s mind, a mind turned inside-out, the components of his practice revealed through the detritus and treasures of our technological culture. In Bartos’s images, we see numerous Apple computers, catalogues from Marker’s 2005 Museum of Modern Art installation “Owls at Noon,” an array of electronic keyboards, a signed photo of Kim Novak, and a 9/11 Commission Report. Of course, these are only the things I saw, what other viewers would notice would be completely different. While we do not witness Chris Marker in a photographic portrait, I would claim that we learn far more from this precise documentation of objects. They testify to the vitality of Marker’s personal space, to the grandness of his editing process and appreciation for the culture in which he was born.

Just before I left Marker’s home, he showed me a scrapbook he’d been compiling for several years, one he probably shared with MacCabe too. Marker had accumulated hundreds of pictures and articles on a young African-American politician who had just embarked on a campaign to become the next president of the United States. Chris was one of the wisest and most prescient human beings I have ever encountered; he was convinced that this virtually unknown candidate could stand up to a historically racist country and win. I was doubtful at the time.

Now, upon rereading Ben Lerner’s eloquent introduction to Studio, I realize that MacCabe’s text and Bartos’s photos are here together to articulate the multi-faceted ways that Chris Marker attempted to “depict old futurisms, a special case of anachronism.” From his wordless narrative science fiction film La Jetée (1962) to his epic reflection on the turmoil of the ’60s Grin Without a Cat (1977) to his visionary CD Rom Immemory (2002), he was committed to pulling us forward and backward in time through both celluloid and digital forms. Studio: Remembering Chris Marker is a testimony to this remarkable quality, albeit in an old-fashioned yet expansive book form.

Lynne Sachs makes films, performances, and web projects that explore the intricate relationship between personal observations and broader historical experiences by weaving together poetry, collage, politics, and sound design. Her most recent film, Tip of My Tongue, premiered at the Museum of Modern Art’s 2017 Documentary Fortnight. In 2014, Lynne received a Guggenheim Fellowship in the Creative Arts.