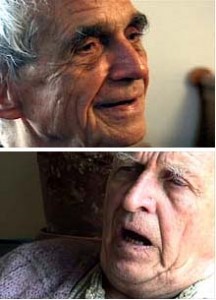

Daniel and Philip Berrigan in Investigation of a Flame

Keeping Alive the Spirit of Vietnam War Protest

By Francis X. Clines, New York Times, May 3, 2001

CATONSVILLE, Md. May 2 — As they round out their eighth decade, the Berrigan brothers, Philip and Daniel, are entitled to retire from the protest wars, but they are still up to their fervid old ways of getting arrested in nonviolent resistance to American military policy.

No one is more delighted at their constancy than Alva Grubb, one of the jurors who reluctantly convicted Phil Berrigan 33 years ago in one of the brothers’ then-famous protest trials — the “Baltimore Four” resisters who spilled pig’s blood on military draft records and helped stoke the furious national debate over the morality of the Vietnam War.

Never ones to protest once, the Berrigans, amid that trial, organized the Catonsville Nine act of resistance: They walked into the Knights of Columbus Hall here in their Catholic clerical garb, seized documents from the Selective Service military draft board and burned them in the parking lot.

“This little village never got over the audacity of their protest,” said Ms. Grubb, a 79-year-old resident who opposed the Vietnam War then and now. “But just look at Phil Berrigan all these years later, still getting arrested for the courage of his convictions. He had very strong opinions and that’s what this country is about.”

Two years’ fresh imprisonment in Ohio for nonviolent interference with a modern weapons system is the reason Phil Berrigan, 77, will miss the Maryland Film Festival’s premiere on Thursday of “Investigation of a Flame.” This is a documentary by Lynne Sachs about the protest events that made this unpretentious suburb on the cusp of Baltimore a flash point for citizens’ resistance at the height of the war.

“Phil’s been consistent; he’s been faithful; he’s been stalwart;” said Elizabeth McAlister, his wife. She awaits his next return from prison to Jonah House, a Baltimore religious residence for eight people who are still dedicated to a level of nonviolent protest forged in the Catonsville Nine days.

“Phil’s been amazing,” said Ms. McAlister, who noted that Daniel Berrigan, who will be 80 on Sunday, has not lost his protest edge either. “Dan was last arrested Good Friday” at a demonstration in New York.

After the film is shown at The Senator theater in Baltimore, there will be a discussion featuring protest participants, law enforcement principals and assorted adherents of the Berrigans’ tradition.

“I left the seminary in ’67 to protest the war,” said Brendan Walsh, a gray-haired activist just up the road in West Baltimore at Viva House, once a sanctuary for conscientious objectors and now a soup kitchen for the city’s teeming poor. “The war keeps coming back; it’s forever,” said Mr. Walsh, noting how it retains a definitive power in American life, exemplified lately by former Senator Bob Kerrey’s admission of killing Vietnamese women and children.

“Back then, we thought Vietnam was some terrible aberration but the country would come to its senses so that we could engage the poverty of the cities,” Mr. Walsh said, grimacing. “To see 250,000 flee this city since then and things get worse for the poor — that’s the craziest thing of all about that war.”

Ms. Sachs, who created an earlier documentary in touring post- war Vietnam, lives here and decided to explore the protest story as Catonsville’s asterisk in history. She found assorted characters still firm to fiery on the topic. The Selective Service clerk, Mary Murphy, once a famous figure here for signing every eligible male’s draft card, remains opposed to what she views as the Berrigans’ intrusion on the government’s war mission, just as Ms. McAlister remains proud.

“This has been an odyssey,” said Ms. Sachs, a 39-year-old who has been fascinated since childhood by the war’s divisiveness. “I’m interested in pivotal choices people make in their lives, the moments from which there’s no turning back,” she said, noting she came to admire the consistency of the mutual antagonists in an argument that still rages.

At the Knights of Columbus hall, the only contentious event in sight lately was a bingo game. But Wilbur Baldwin, a 79-year-old veteran of World War II, recalled the Catonsville Nine days and his distaste for the behavior of the dissenters.

“The Berrigans are troublemakers,” Mr. Baldwin said. “That’s a war we never won,” he said, looking back and glowering as he blamed the use of the defoliant Agent Orange for the death of his brother, Frankie, in Vietnam. This was exactly the sort of war technology decried by the Berrigans, but Mr. Baldwin was adamant. “The Berrigans are troublemakers.”

And on a good day, they remain troublemakers, by the accounting of Tom Lewis, one of the Baltimore Four who, like the Berrigans, has been arrested many times over the years. Most recently Mr. Lewis, a 60-year-old artist close to the Catholic Worker movement in Worcester, Mass., was arrested at a Raytheon weapons factory where he prayed and blocked a road to protest against a part of the Star Wars research program known as the “Exo-atmospheric Kill Vehicle.”

“My feeling is the Vietnam War was a war against the poor,” said Mr. Lewis. He views Star Wars as a continuation of the same issue from his protest youth, contending that it shows military spending as overshadowing the unmet needs of the poor. “There’s been a certain consistency in making nonviolent creative statements against the madness,” the aging protester said as he took inventory on all the troublemaking still sparked by the Catonsville Nine. “An important consistency.”