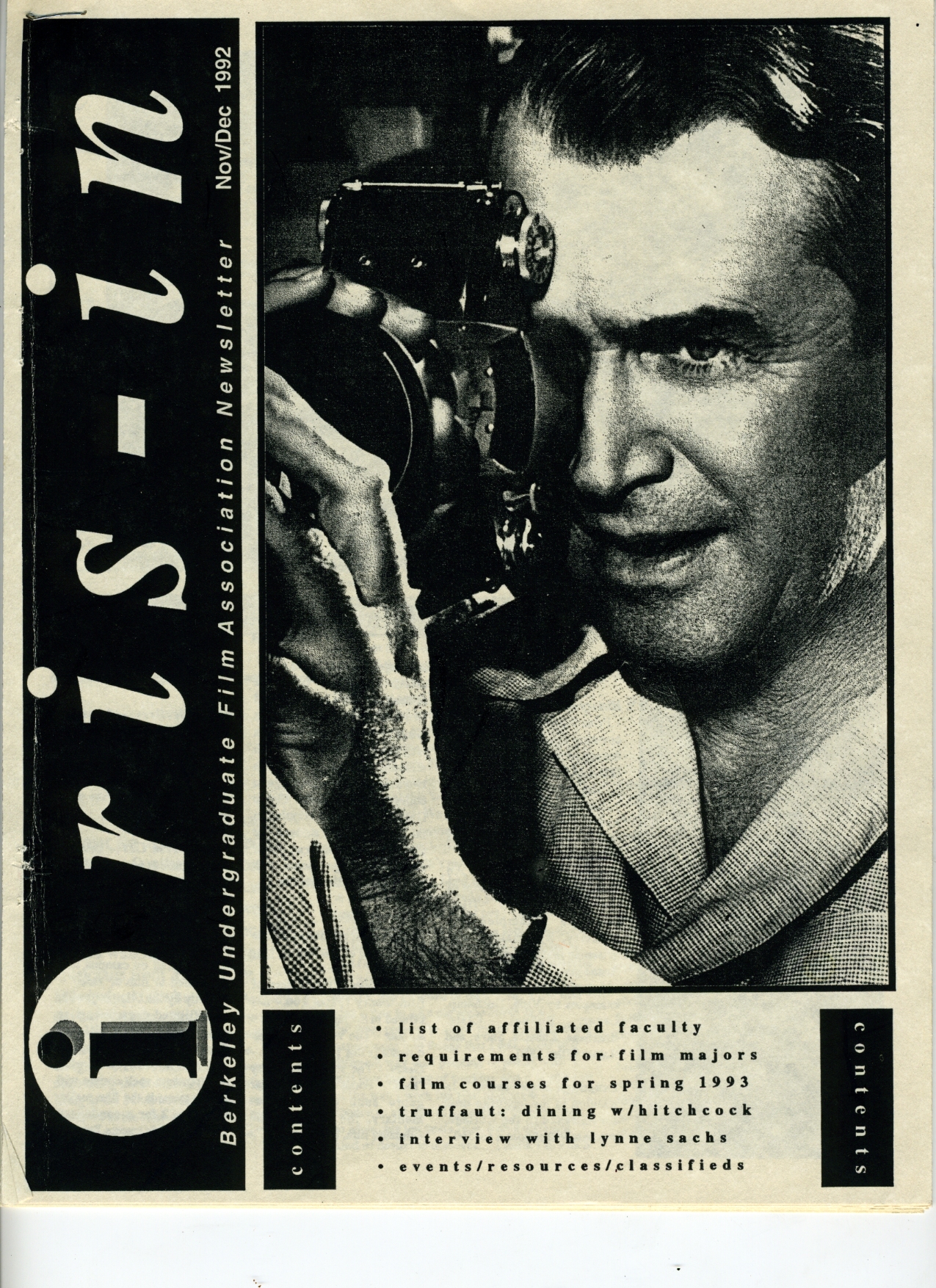

I RIS-IN

Berkeley Undergraduate Film Association Newsletter

Nov/Dec 1992

Interview with L. Sachs, filmmaker and visiting instructor at U.C. Berkeley by Karen Rester

LS: …when I was about 18, I had a Summer job at a place called the Center For Southern Folklore stuffing envelopes for a fund- raising campaign. There were these quilts all over the place and potters walking in and out and musicians fromYazoo City, Mississippi or wherever. Actually, they had just made a film called Four Women Artists; it was about a quilt maker, a painter, a needlepoint artist,and someone else. I thought, “This is incredible this …way of discovering the South.” I didn’t really like living in the South because I didn’t really like Memphis at the time and I thought, “Ob, there are greater horizons somewhere else.” But I liked this sort of side of the South that was not so easily accessible and that was so much about secrets and pasts and the ways that people made things out of nothing, and so I hung out there for longer. They had just acquired the whole film, photography, and sound recording collection of Reverend L.O. Taylor that year; he had died in 1977. The Center started interviewing people whose pictures were in the photographs and I had a job transcribing the sound recordings that he’d made on 78 rpm discs. He was a preacher who also made films in the 1930’s and 40’s. I was astounded at this way that be interacted with the community. We took the films around to churches that summer and then I went away to college. I remembered what I had done that summer but I didn’t really think that this had a big impact on me. I had always been involved in the arts and I kept doing paintings and poetry and things like that but I also got really involved with history; I was a history major in college. At least years later I discovered that film was a way to draw on my art interests and my interests in things like these people that I’d met or heard of back then. Film was also a way to take me somewhere as ~ different person, to allow me to integrate these experiences into things that I was doing in a different way than painting or poetry was. I still love that way of working and it is still part of the way I work but film also gives me the chance to ask lots of questions, or to go back to Memphis ten years later with a different kind of desire, to discover… I think I’m much more curious about the world than I was then (laughs) and about not just the world but what was right next to me. So that was kind of how I first got interested in film.

House of Science, Personal Films and Other Dangerous Substances

KR: YOu don’t consider yourself exclusively a filmmaker in the sense that you often incorporate your own collages, sculptures, and poetry into your films.

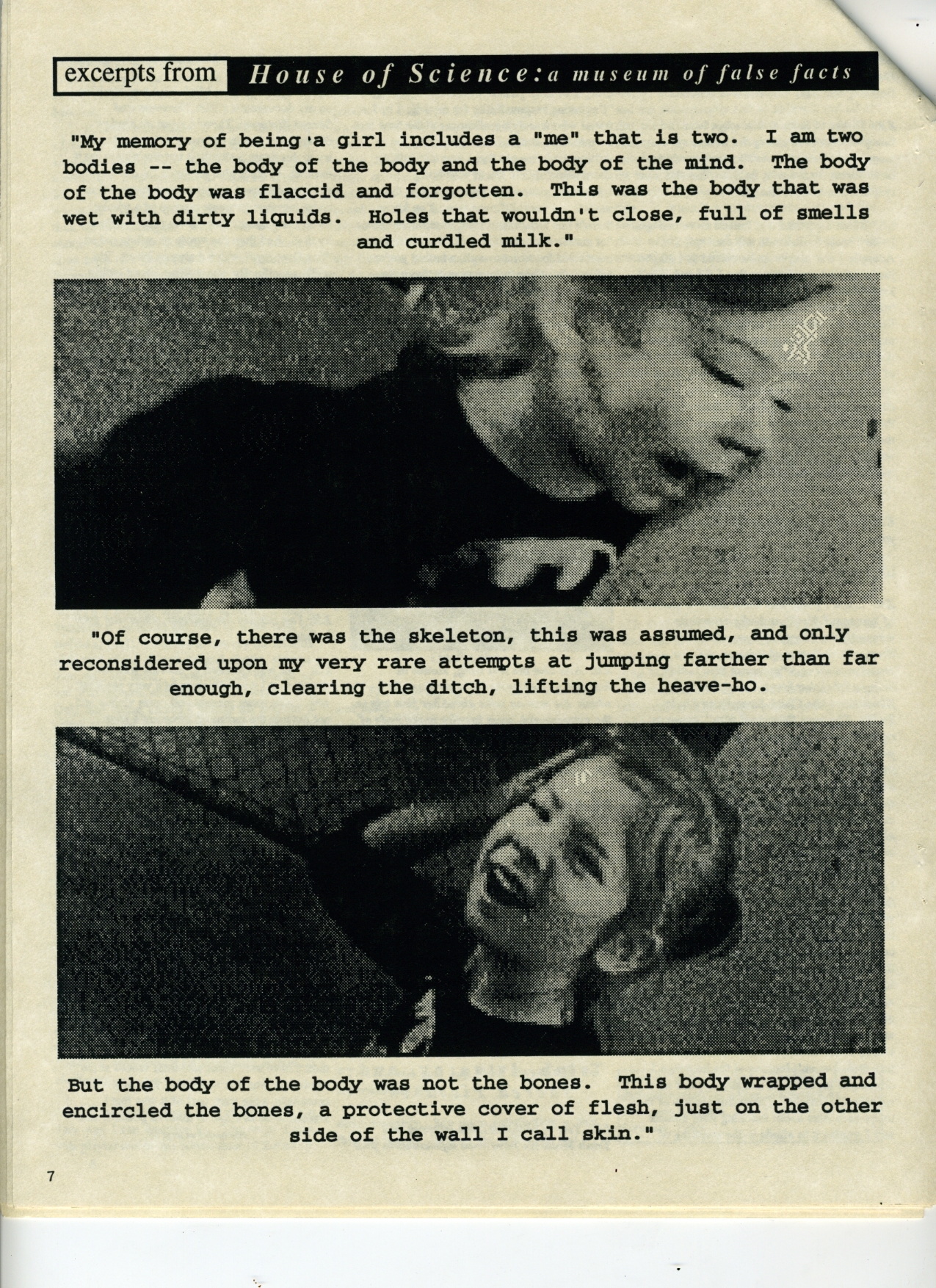

LS: Yes, the last film I did, House of Science, and the one I’m working on now were kind of installations, sculpture pieces at first. The new film is tentatively called States of Unbelonging. I did a sculpture piece that allowed me to work with all these different materials…but actually a lot of it was film. I took film frames and put them into handmade slides, if you can imagine this, with dirt and feathers, all different things, and then blew them up; they’re really beautiful. [The film] is about letting the material speak to me because I’m not that good at sitting down and writing out a script. I like to be open to thoughts. I did say to myself this time, “I’m going to do all the production and then all the post-production,” but I just can’t work that way. I’m awed by people who can. With House of Science, I wrote the end when I was finishing the film. The end was the end.

KS: House of Science has often been interpreted as addressing the notion of women as constructs, that is constructed by institutions, by Science, by Art. Was this your original premise for the film?

LS: It just happened that I made those collages [which seem to illustrate this concept]… Actually I was maybe embarrassed and maybe just confused about things that I did and didn’t know about my body. I wouldn’t say that I was bitter towards Science, or maybe I was a little bit, but Science is a big word and it has more to do with being awkward because you don’t have the tools. And I didn’t have the sort of language to know even bow to talk about certain kinds of physical experiences. I felt so especially as a young person. I made the film, I think, when I got to the point where I did feel more comfortable. I could look at that uncomfortableness of the younger period and say, “I’ve changed a little bit. Now I feel that I can make something that’s about that.”

KR: It was really a personal experience for you…

LS: Yes.

KR:…and I guess this leads into the question of “personal films” and why especially women filmmakers feel compelled to make them. With House of Science did you envision making a “personal film” – this being a label that has been applied to filmmakers like Chick Strand and Linda Tadic. The term “personal film” seems to refer to an opening up on the filmmaker’s part; perhaps the desire as bell hooks has put it, to move “from margin to center” as a woman. TO open yourself up so fully to the spectator that they can’t ignore you. You’re exposing yourself, you’re communicating to other women, and at the same time you’re creating filmic art.

LS:

I think it was wanting to…feeling that there was such a thing as a community of women and such a thing as working with a language that was so personal that it communicated first to women on one level and then to men on another level. I never wanted it to be exclusive at all. But I do think that men and women read differently…their schematic is different because we walk through the forest and we look at the stars and somehow see them a little bit differently, and so I wanted to delve into that I wasn’t looking at the language I developed for this film and saying “this is specifically female.” I have this section of the text which talks about touching your breasts and I wanted it to allude to the touching of your breasts when you’re looking for bumps, cancerous bumps as we’re supposed to do, and I think it’s really great if women do it and think “I’m taking responsibility for myself. I had a friend who was dying of cancer at the time that I wrote that. But as I was writing it, the writing made me see that I was also talking about being able to touch your body. Interestingly enough several men saw this section in a very different way. You know there’s this thing about masturbation and men: “of course every man does “. But it’s not very celebrated for women at all, whether you’re talking about pop culture or even from the most intimate of diaries — looking out or coming from within. (pause) Modern mythology has created this rite of passage for men and not for women. I wanted to say that touching your body if you’re talking about masturbation is like part of this change, a coming into being autonomous. So with that one section I’m always curious how people read it and women often see it as talking about checking your breasts for bumps while men seem to interpret this more sexually. I’m thrilled by this ambiguity.

KR: And also the title itself, House of Science, as well as the opening scene in which the woman talks about her first trip to the gynecologist, seem to refer to the body of woman as being experimented upon.

LS: And that you need a guide.

KR: And that you need to be told how to look at your body.

LS: Yes. And so I didn’t want there to be the need for a guide whether you’re talking about masturbation or about the preservation of your existence. But it’s interesting to see how people who’ve lived in the world in different ways look at my film. There are a couple of places that people have read as being about AIDS. I never even knew that that was in the film, but the way that I wrote about liquids and bow you struggle to keep them in… People have told me that it would be just as accurate for someone with a disease.

Trinh, Irigaray, and Sacred Pictures

KR: You’ve said that Luce Irigaray and Trinh Minh-Ha have been influential in your work and writings. How so?

LS: When I first met Minh-Ha I was working on my documentary film, Sermons and Sacred Pictures. There’s a certain kind of distance she has in her work as in she doesn’t try to dominate a situation but she tries to let it unravel. This is also reflected in] the way that she uses different voices so that many voices come together to create a sense of a whole; there’s not a hierarchy. I was really intrigued by that. And then she wrote an article called “Ear Over Eye” which I always loved. It’s really specifically about film; about letting there be silences. In Sermons and Sacred Pictures, I wouldn’t necessarily say I had silences but I had these places – black sections that were like visual silences. I wanted them to fragment the film and it frustrates some people. I wanted to say, “This is not a completely whole picture of a person,” because I didn’t even know the person. I can only say what I gleaned from listening to people, and from working with bis [Reverend Taylor’s] materials; from taking myself back there and from being from there originally. I didn’t want to make a film that recreated something I would be projecting on.

…There’s another thing that I remember hearing Minh-Ha say which had to do with the ways of shooting; that the zoom lens gives you so much power and doesn’t bring your body into [it]…

KR: You remain the outsider, observing from a distance.

LS: Yes, and I wanted to interact with the people that I was talking to in a very physical way…to be more present and more visible and not outside the radius of someone’s gaze. …There is a kind of intimacy that is instinctual. In a documentary you have to be more participatory as well as more knowledgeable about the potential of your equipment.

KR: But in Sacred Pictures we never see the people you are interviewing. Their voices are never presented as “actual sound” and this seems to create a distance.

LS: Well I did that whole film, I shot it and recorded it, petty much by myself. I was talking to people that were just meeting me and they were at first kind of uncomfortable but then they really opened up. I felt like not having a camera there made them feel more at ease. I just recorded it on tape; there is no synch-sound in that at all. This is a big issue that I still have a question about. I couldn’t sit here and say, “This is my ethic. The reason I didn’t have their faces and their voices at the same time was this and this.” Part of it was economic, a big part; part of it was that I wanted to be as close to them as possible and not to be distracted by cameras and lights and things like that. I just walked all over-the neighborhood that Reverend Taylor had lived in with my camera. I saw neighborhoods I didn’t even know existed, just beautiful neighborhoods and parks …it was like a new city… and I wanted to do it by myself. To use a crew would have been really different. So, that was the film that I was able to make on my own. When I finished it some people, mostly other-white filmmakers, said, “Don’t you feel strange that you went into this community” as if they would be very assaulted that way. I think, and I heard

this from a Black professor at Howard, that it would have been condescending if I had decided nott to make it because I was white; he was really glad that I had. Not to say, “Oh, you understand,” but not to let those barriers stop you right away. I know so much more about the black filmmaking community from making this film.

***

KR: Talk about Irigaray

LS: Well I was part of a women’s reading group about five years ago with Peggy Ahwessh and Jennifer Montgomery; a lot of filmmakers who were here now don’t live here anymore. But we were all reading Lacan for the first time and [continuing to] read feminist theorists [such as lrigaray and Helene Cixous]. None of us had studied that in college so it was completely coming from what we wanted to bite into, which to me is exciting; it wasn’t passed down from some authority figure. So we would meet at somebody’s house and each of us brought a book… It was very very serious and we all felt terribly guilty if we didn’t read what we were supposed to read. I think it affected all of our work quite a lot. You asked about responsibility- I felt like I had to [incorporate what we had been reading into House of Science], partly because I was in this milieu, mentally connected to a group and grappling with issues about the identity and the experience of being a woman. But also I was so stimulated by lrigaray. It colored the way I was writing, just how she looks at the body in this really visual way. She’s not talking about art at all but..she sort of theorizes physical things; the body becomes all these different faces of mirrors so that your mind is like a mirror onto your body and you learn about a certain kind of philosophy that comes from – people say lack but she doesn’t use that word – that comes from a body that contains holes, or a body that welcomes them…And even if it was essentialist it didn’t bother me, it intrigued me. It was sort of lauding something that I’d always felt but that I hadn’t been able to embrace somehow intellectually. I didn’t even realize how much she had influenced me until I had a show in Los Angeles soon after I had finished House of Science . A woman raised her hand and asked, “So, when did you start reading Irigaray?”

On Lifting Belly

I love Gertrude Stein now. I was reading Gertrude Stein when I was making that film (House of Science). I knew that she was going to figure into it. I liked the way she played with words… sort of non-linear but still driven by some kind of illusions, but not metaphoric because I’m always fascinated by metaphor and I like that she wasn’t, that she worked with other kinds of linguistic plays, tropes. I was reading her poetry one day in bed and I started reading it out loud and it was completely different…it was like “Ahh” that’s what it is, it’s supposed to be out loud. And so I had the poem and I loved that it was about lifting belly, like about weight or about flesh or about…just that word lifting belly sounds really fantastic; it’s very female. So I thought that I’d ask my friend who has a 16 year old daughter to read it. Well the daughter could not stand it because it was too haphazard for her. You see, she was coming to an understanding of a rational way of speaking, but Stein was pulling her back to some way of speaking that is extremely creative but deceptively childlike. The daughter wanted desperately to get into adult life and adult language and it made her really uncomfortable to read that whereas her mother loved it, and so we just decided to read sort of as a round together; I decided to leave in the part where we mess up. So, that’s how that happened.

Film as Weapon

KR: What does this tendency in women avant-garde/experimental filmmakers to make personal films mean to you?

LS: I would never say that most women want to make personal films. I think there are many women who would love to make impersonal films but who only want to see their name slapped alongside the title “director” or “producer”. I see myself as a filmmaker, and maybe that term harkens back to a much older term, one that we now tend to shiver at the thought of: homemaker. But what I like about it is the non-hierarchical position it takes. This kind of personal work comes from a place that is very critical, often angry but presumably grounded in an artist’s experience and vision. In its honesty it is a kind of filmic expression that can be subversive and I think expressive.

KR: Do you see you work as a weapon?

LS: If in any way I were to think of myself as a weapon it would be as a weapon against stagnated thinking. I want to trigger my audience into thinking differently and independently.