MFJ / WORLDS / FALL 2022

From 1967 to 2017, Japanese film artist Takahiko limura lived with his wife Akiko in New York City. At the same time, he also lived in Tokyo. Both places he called home. When he was in town, he was an avid member of the local media art community. He premiered new work and energetically attended screenings in venues that celebrated the avant-garde. Taka, as everyone called him, devoured all the art that he experienced in New York, eventually writing a robust New York Art Diary which covered the first two decades of his time in his life. At every turn, he approached the making of an image or the recording of a sound from a distinctly Japanese perspective, always aware of the difficulty of translating words and ideas from his language and culture co ours. His material preoccupations originated with the apparatus-both the camera and the projector– acknowledging everything from aesthetics to psychology to semiotics.

In 2010, I visited Taka’s studio in Tokyo with my husband, filmmaker Mark Street, witnessing his expansive workspace, filled with film, video, and other media detritus. We drank beer, ate local snacks, and talked about the NYC underground film community. A few years later, I attended one of his expanded cinema events at the Microscope Gallery in Brooklyn. Usually when we anticipate a film screening, we assume that we will sit in a chair in a row of other chairs, all facing in the same direction toward an illuminated screen. A Taka limura program would be a spectacle of an entirely different kind.

Taka never accepted any of the rules for making or watching a movie. To experience one of his cinematic events always took you beyond seeing and hearing. Committed to exploring the ontology of cinema, he wanted you to think about audience, the frame, language, the body, light and shadow, the difference between the Western and the Asian psyche, and time.

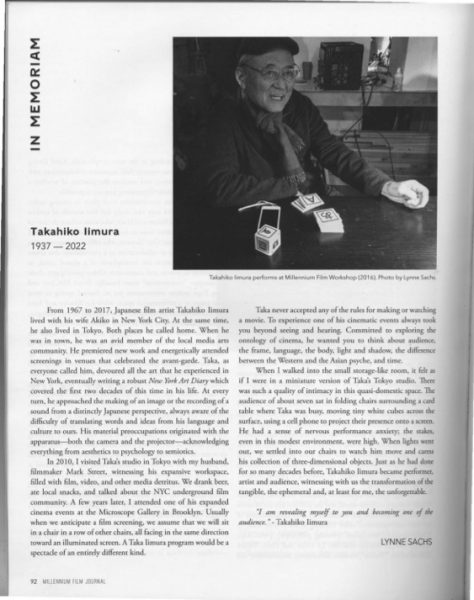

When I walked into the small storage-like room, it felt as if I were in a miniature version of Taka’s Tokyo studio. There was such a quality of intimacy in this quasi-domestic space. The audience of about seven sat in folding chairs surrounding a card cable where Taka was busy, moving tiny white cubes across the surface, using a cell phone to project their presence onto a screen. He had a sense of nervous performance anxiety; the stakes, even in this modest environment, were high. When lights went out, we seeded into our chairs to watch him move and caress hi collection of three-dimensional objects. Just as he had done for so many decades before, Takahiko limura became performer, artist and audience, witnessing with us the transformation of the tangible, the ephemeral and, at least for me, the unforgettable.

“I am revealing myself to you and becoming one of the audience.” – Takahiko limura

LYNNE SACHS