Seeking to Grasp Wind:Interview with Lynne Sachs by Wai Choy

Friday, April 21, 2006:

I wake up in a daze. I glance over at my alarm clock, which is blurry. I put my glasses on and the time 9:32 AM comes into focus. I rub my eyes in disbelief. Impossible. I check my phone clock. 9:32 AM. I look in the lower right hand corner of my computer screen: 9:33 AM. A sick feeling sets into my gut. I’ve missed my 9:00 interview with experimental filmmaker Lynne Sachs. Reeling from this realization, I pick up my cell phone and call her. “Professor Sachs I’m so sorry I missed our interview,” I croak out in my morning voice, probably unintelligible. “…Um…here she is,” the young voice of her daughter on the other end replies. Embarrassed, I sheepishly count the next few seconds until I’m greeted by Lynne herself. I apologize again and Lynne is nice enough to let me reschedule the interview for Sunday at 8:30 AM. I thank her and hang up.

Saturday, April 22, 2006:

Today I wake up with a mission: to ensure that I’m not going to be late for my 8:30 interview tomorrow. I take the 6 train to union square and buy a new alarm clock at Circuit City. When I get home I set it up – my new trustworthy guide. It has backup batteries. Before going to sleep, I set my alarm for 6:10 AM. I also set my old alarm, my phone alarm, and my girlfriend’s phone alarm.

Sunday, April 23, 2006:

6:10 AM

I’m up, but the sun isn’t. I cook some breakfast and pack my bag with my interview notes, my tape recorder, and a notepad and pen. It’s raining outside, so I grab my umbrella and head out. Standing on the corner of Lafayette and Canal St., I try unsuccessfully to hail a cab. The minutes tick by, and the irony of leaving an hour and a half before my interview, only to be thwarted by not being able to get transportation hangs over my head, mocking me. I begin to get nervous and my heart beats faster and faster. Finally, in the distance, I see a lone taxi parked on the curb. I walk toward it. The cab driver nods to me as I get closer, and the clichéd ton of bricks lifts off of my shoulders. I hop in and tell him to take me to Brooklyn.

7:45 AM

About twenty minutes later, I find myself on the deserted streets of Brooklyn, 45 minutes early for the interview. I haven’t been awake this early in forever. I take a moment to reflect upon how much more I could do with my life if I woke up this early every day. It feels good. I see a café and I go inside to grab a bite, pass the time, and go over my plan for the interview. During this time, I think about how I could possibly write a concise biography of Lynne – someone with such a vast body of work and years of experience as well as all the intricate dimensions of a unique woman.

I decided that a traditional, simple introductory bio would be best, the information of which I found on the internet. Her true biography will come through in our interview and her responses to my questions.

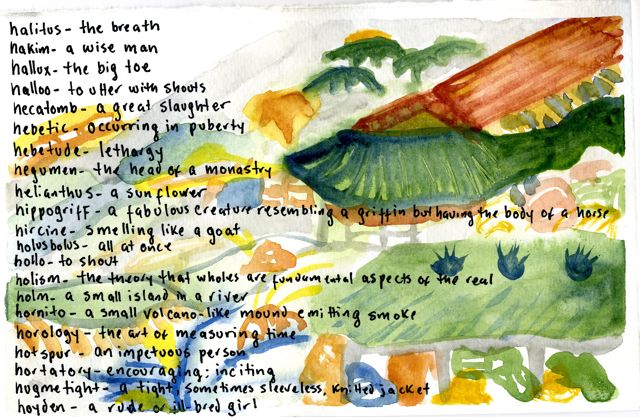

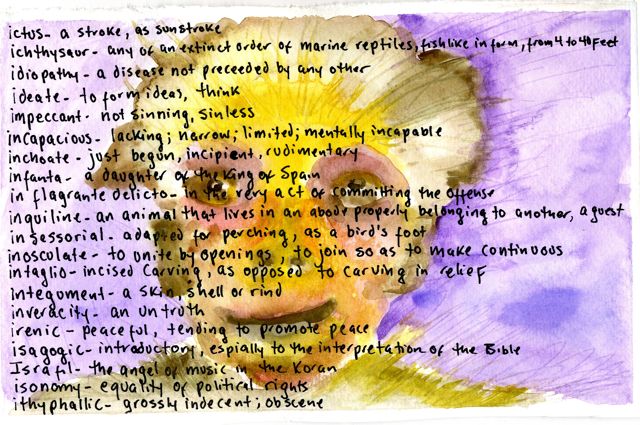

Lynne Sachs is from Memphis, Tennessee. With her films, she tries to “expose the limitations of verbal language by complementing it with complex emotional and visual imagery.” Her experimental documentary films “push the borders between genres, discourses, radicalized identities, psychic states and nations”. She has been making films for over 20 years, ever since she discovered filmmaking in 1983. In her preceding years, Lynne had been painting, making collages, and writing poetry. Stemming from her interest in collage is her fascination with the new ways of seeing images when two disparate images are superimposed upon one another. Her work is very personal and explores the relationship between personal memories and broader, historical experiences.

Lynne graduated from Brown University with a degree in History. She received her MFA from the San Francisco Art Institute, where she discovered experimental film. She has received numerous fellowships and grants to make her films, many of which have won awards and distinctions. Her films have been screened at the Museum of Modern Art, the Pacific Film Archive and the San Francisco Cinematheque as well as other exhibition sites around the world. She has taught filmmaking and film studies at the University of California at Berkeley, the California College of Arts, the New School and Temple University, and New York University. She has two daughters, Maya Caspian Street-Sachs and Noa Moncada Street-Sachs, with her partner, filmmaker Mark Street.

8:15 AM

Leaving the Café, I walk over to her house and stand outside, looking up at the dark windows, wondering if I should ring the doorbell or not.

8:25 AM

I press the button on the intercom and I hear her say, “Coming!” Moments later, Lynne appears at the door, hair wet. She’s running a little late and I’m a little early. Splitting the difference, we’re on time. She invites me in and tells me that I can wait in the living room while she gets ready. I do. I look around and notice a piano, various pieces of video equipment, and children’s books. Her black cat watches me warily and I watch back.

Lynne reemerges and, grabbing her umbrella, leads me quietly out of her house and into the street. We walk over to one of her favorite cafes, but it is closed, so we push on until we get to another café. We sit down at a table and, disregarding the food menu, she orders coffee and I order tea. I test the tape recorder and, finally, I’m able to ask my first question.

WC: Where do you start with each film? Could you please describe the process you go through?

LS: Some people would say that a film for them starts with a story. My films generally start with an idea, and they start with a sort of trigger: something that can be an observation that I make in my daily life – a kind of awareness or a realization I have today that I didn’t have yesterday – and then from the idea it evolves into a series of relationships where I start to make connections between that initial impulse that struck the creative side of me to other threads in my life.

So initially I have to find that I’m really enthralled by something, and then other associations – in a sort of collage way, but more internal – start to layer on top of that and start to create other dimensions by which I can understand, I could even say, a phenomenon, like a scientist in a way. I start to see that there are repercussions that happen. For example, the fact that the people in the Catonsville Nine did this act of civil disobedience had a relationship to me because I’m interested in political issues: that’s the obvious connection. I’m interested in how war affects people’s daily lives.

With me in a sort of more private, universal way, I was interested in someone making a choice from which he or she can never go back. You only make a few choices like that in your entire life, where you do something and then you lose control. It could be having a baby, it might be getting married, though not exactly these days…at all, or it could be breaking the law, or it could be doing something you believe in because you think it transcends law. So when things like that occur to me – and I first heard about that historical event – it then had other layers of meaning, and so in my other films, it sort of works that way too.

WC: Thanks. I’m just going to check to see if that recorded.

[Click]

WC: So…if your films start with ideas that you’re enthralled with and observations that you make, to what extent is your work personal?

LS: I would say all my work is personal. I actually didn’t give you an earlier experimental documentary I made as my graduate thesis, which was a film about an African-American man who was a Baptist minister from Memphis, where I grew up. And he was also a filmmaker in the 1930s and 40s, and what interested me was that he was shooting from the inside out. He wasn’t an anthropologist or a Northern photographer coming to the South in the 30s and 40s to see how black people lived. He was living it himself, and he had an exquisite eye. His sense of aesthetics was unbelievable. So I came across his films when I was in high school, during an internship, and then I went back many years later in graduate school and made this film.

So someone asked me when I made it, well, “Where are you in it? Why don’t you put yourself in it? Why don’t you speak in it? Why don’t you figure out your place?” But I felt in that film it was more like my fingerprints were all over it. It was the idea that I wanted to revisit my childhood home from a completely different perspective, and I talked to eleven people who were total strangers to me, who were either people directly associated with him or people who remembered his films from being a child in the 30s and 40s.

In documentary, you have the dialogue and you don’t have to put your body or your skin there. It’s the energy that happens between you and other people. And in my work, the personal part also comes with the shaping of the images: the sculpting of the sound and the pictures is something that only I would have done. So I’m not following anyone’s formula, which I feel would be impersonal.

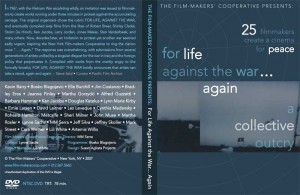

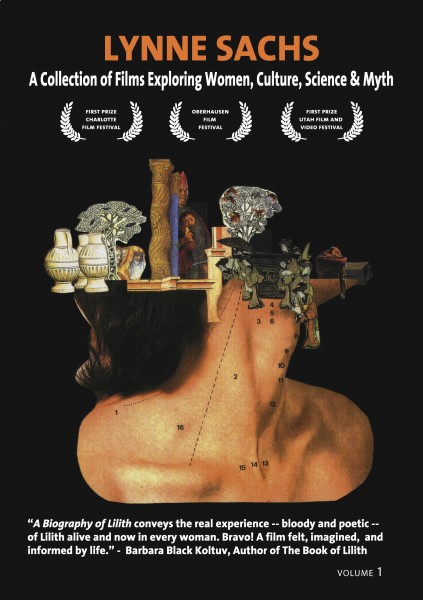

And then of course I have these other films, and somehow, over my twenty years of making films – I made super 8 films when I was very young – I’ve kind of gone back and forward between intensely personal films, and films in which my presence is less obvious. So I made something like The House of Science which is full of diary passages, or Biography of Lilith, which has my actual body in it and poetry to something like Investigation of a Flame, where the gathering of those people in the 2000s, 2001, 2002, actually I’m still meeting with them, happened because I made them happen, but my face is not in the film and my writing is not in the film. It’s the energy of bringing the elements together.

WC: So do you shoot your own work?

[This question comes out of my mouth too quickly and I realize, sheepishly, that I’ve stopped her with her coffee cup halfway between the table and her mouth. She gracefully puts it down, choosing the question over the beverage.]

LS: For the most part I shoot my own films. In a little bit of biography of Lilith – the parts which I consider kind of narrative-ish, where the characters move – I’d just had a baby a few weeks before and she was very demanding of course, and also I wasn’t so comfortable working with actors, so I brought a friend to shoot that part. The rest of that film I shot: The flowers, the spiders, the landscapes. Then, in States of Unbelonging, the issue of who shot what are very mixed up and very much part of the dynamic of the film, because I was trying to imagine Israel and Palestine through media and through my friend Nir, who is a former student of mine, and through other images that people sent me, going back to the 80s.

So it had to do with not shaping, with a kind of restraint…and the film is all about not…not allowing myself to be able to witness that part of that world directly – to have to situate it in my mind, in my imagination. I finally do go, and I finally do shoot film there, so the camera is very much an extension of my creative process and my interaction with real world experiences. But in States of Unbelonging it was a dynamic about when it would enter my own grasp.

You saw Which Way is East? In that film I’m making a film about Vietnam with my sister, and she knows Vietnam very, very, very well…and I don’t. So she thinks I use the camera as this buffer, as a way to not interact, and that I should open my eyes wider and not always be looking through a frame. She says in the film, “You’re always framing everything.” So it can be an obstacle, perhaps. For me, in that film, it was a way for me to see better. Or not just in that film, but in that place. I felt that I had a kind of patience that I wouldn’t have had as just a tourist.

WC: Because the frame of your camera focused you.

LS: Yes.

[This makes me think about the act of filmmaking and whether or not the physical parts of it – the frame, the film, the human operation – are limitations at all. Perhaps it is those “limitations” that form the essence of films…the personality of films. As Lynne was talking about before, the choice of the shots and the choice of what pieces make it into the final cut of the film that creates interesting energy. Some people point out that film is unable to capture reality, because the frame in and of itself is exclusive of all reality but that which lies within it. But maybe the frame doesn’t exclude, but rather focuses us and allows us to perceive the world around us and see things that often go unnoticed.]

WC: I remember that you talked about the House of Drafts online project, and how you and your colleagues worked to abolish the idea of ownership of images: “I shot this, you shot this, this is my footage, this is your footage.” Would you please expand on this idea of images being owned by everyone instead of the individual and talk a bit about your use of found footage in your films?

LS: Found footage in House of Drafts?

WC: No. In your films in general.

LS: Oh okay. Because I don’t think there was any found footage in House of Drafts.

WC: [Laughs] I know.

LS: In House of Drafts, which is a web project, first of all we had very practical issues. It was not all high-minded idealism that led us to creating a repository of images or a treasure box of images. We had limited access to equipment. So we had one NTSC camera and one PAL camera, and as most media people know, those are not compatible. So we had to change PAL images to NTSC images and NTSC images into PAL images. That sounds all very technical, but the thing is it’s very interesting because it has to do with these international obstacles or walls that exist between cultures. They can’t look at our images unless they have the money to do transfers, and we can’t look at theirs, so it means that we can’t see their world. We only see their world – in this case it was Bosnia – through broadcast television or mainstream film and feature films…fictionalized films. And they see our world through CNN or Hollywood.

It’s really disconcerting to me that these video standards, which I think were probably initiated by the United States to censor us, to censor us not just as creative people but image makers of any kind. So the way we wanted to work together was that I was looking at Sarajevo as an American tourist. My images were also shaped by my interactions with Bosnian people, and their images were shaped by their interactions with these international people – with Americans – so that the images weren’t weighted so much by our past. They were more about something that was shared by all of us as artists. And that was kind of exciting for us.

We didn’t want to have “his” and “hers,” we didn’t want to have “yours” and “mine.” We wanted to let the images be created by us as a group, but also to let the images look as if they were created by the characters. So by putting them in this shared realm, they were separated by our specific experiences. So that was exciting, and it meant that the editing process was more dynamic, because in some sense, those images became found images – you asked me to talk about found images.

WC: Yeah.

LS: They became “found” because they became allegorical or they became more associative than they were literally about different people and moments with the camera: “Oh, I pushed the button then and you pushed the button later” – like that. We didn’t have to remember that. Now about my relationship to found images: First of all I think that there is a difference between found images and archival images, though in a sense they exist in the world in the same way. Archival images have a more obvious relationship to specific historical events, not to say that they’re objective because whoever shot them or made them occur or paid for them interject some subjectivity. But those images do have a correspondence to history, and often I have an interest in archival images that is respectful, that is reverent, that is not necessarily trusting, but um…is confidant that they will lead me to a slightly better understanding of something that happened.

WC: And found images?

LS: With found images – and they could also include archival images – I have no reverence. I don’t necessarily have any respect. I have more intrigue and I feel like it’s my job to manipulate them for the piece as a whole, you know, to make them function as parables, to make them work as transitions, to make them work for me for humor, to give more dimensionality, to have fun with them. I’m interested in that distinction, and I’m also interested in creating a little confusion with my audience about when to trust me, when to think the images do have a relationship to history or to the objective world, and when the audience starts to say “hey, this is all just a mish-mosh that is meant to take me into another way of thinking.”

WC: That’s a great distinction. So I guess the next kind of generic question that everyone asks, and I have to ask, is, who and what are your influences and how do they reflect in your work?

LS: My main influence is a man named Chris Marker, who is still alive. He’s in his eighties. He’s a very active film and video maker. He started out in the era of the French New Wave. He was making films around the same time as Jean Luc Goddard and continues, as does Goddard. His films are very keenly observational and idiosyncratic, and there’s a group of people in the world who are obsessed with Chris Marker – there’s lots of us. He has a really devoted following and he works very much by himself. I met him when I was in college, and I had written a paper about his films, and I sent it to him and he called me and we met in San Francisco, and we talked for hours, and he had met Roland Barthes…do you know who Barthes is?

WC: Yes I read some of his essays last year.

LS: Yeah, well they knew each other, and I had compared his films to Barthes, and he said, “Oh well I think Barthes may have said some of that differently” and, you know, he’s very intellectual but also very whimsical and private and…he’s a wonderful person. His films are essay films, and I think of my films as essay films. And then I would say Chantal Ackerman. She’s from Belgium. Do you know her work?

WC: I’ve heard about her but I haven’t seen her work.

LS: She’s made feature films and she’s just very interesting, and feminist, and also creates nuances to that moniker. And then I would say, Stan Brakhage, with his idea of the camera being an extension of your inner being, and physically that you move with the camera, and my resistance of the tripod. You’re more physical and your “corpus” is more integrated with the camera when you follow the way of working that Brakhage did follow. Uh and then…um…I would say Craig Baldwin, whose films I showed in class – I screened Tribulation 99.

WC: [Laughs] Yeah.

LS: His use of found footage has definitely influenced me and excites me and is very dynamic…very full of energy and also works with the sensibility that we call “dialectic”, where you create new meaning through conflict and opposition. So those are a few people.

WC: Cool. So you mentioned Stan Brakhage as one of your influences, and I know that he never work printed his films. He wanted every piece of his final product to be touched and done by him and he embraced the natural imperfections that happen to the physical film. Do you feel that something is lost or changed in the many steps of the film process?

LS: I do think that a great [inaudible thanks to the excessively loud waitering] for the down and dirty method of art making in general, where you welcome the universe into your hermetic environment. You say, “Oh dust is okay. That’s what was going on that day. That’s a little emblem of the hemisphere, of the air, of the ambiance.” So there’s something about loss of control that’s really exciting and helps you come to a new awareness. It’s like the environment becomes your friend instead of your enemy. But I don’t always follow that. I say that in an ideal world.

In another world I’m very…I pay a lot of attention to every single shot, I like films to be without dust…it’s this whole thing about dust…I wish I could make a film about “dust”, ‘cause then I could welcome dirt and dust. You know, it’s a give and take. In some ways I’m very casual about the way I shoot. It sounds funny, but I don’t change my lens for every change of location because I want to be less obsessed about that kind of thing. But then there’s this whole transition to the digital realm, where everything stays pristine once you have them in your computer, and then I find that I have a lot of worries around the computer too. It just changes. It’s this other element that becomes and obstacle. I’m trying to take the lead from the technology as well as to lead the technology myself.

[Coming from a conventional film background where imperfection is unacceptable, I’m fascinated by this concept of working with a film with the mindset that whatever happens along the way – whether it’s scratches, collection of dust, etc. – adds to the authenticity of the film. I could never work in the way that Brakhage does. It is hard to give up control and submit to the natural occurrences surrounding physical film. Much like Lynne, I want my films to be without “dust.” I don’t want physical dust – specs of dirt marring the perfection of my film. Perhaps there is room in my future work, however, to let in the spontaneous and the accidental – a different kind of dust.]

WC: So to go with the subject of technology, I know that you recently transferred much of your material from film to digital format and DVD. Can you talk a bit about how the new format has changed your work, if at all? Does the transfer from film to video change anything?

LS: With regards to the digital format and the internet, if you have the patience for it, I was really excited about making the piece The House of Drafts on the web and that it allowed for an international conversation in the making process. With my DVD compilation, it was kind of thrilling to go back to those collages and then I made new collages. I didn’t let things go to bed. Things from the past came back to life, and that was really because of the DVD. The collages from The House of Science became available to you, the viewer. And that DVD has kind of taken off and given new light to those films, which were created in the 90s, because they’re on NetFlix, and they’re on lots of different internet distribution modes.

I don’t know if people are interested in it because it’s my compilation or if it’s because there’s something about Lilith in it…I don’t know. But it’s sort of taken off in a way that I was hoping for, but wasn’t sure was going to happen. I’ve gotten e-mails where someone said, “I saw your film in a store in France,” and in lots of other different places. And lots of places have bought it – both wholesale and retail. One of my favorite museums in the world is called the Exploratorium. Have you been there?

WC: No I haven’t.

LS: It’s in San Francisco. It’s a really innovative science museum. They keep buying DVDs of that.

WC: That’s great!

LS: And uh…I don’t know why. But it’s an interesting place for me to imagine my work being available to consumers. And that wouldn’t have happened without DVD. People didn’t buy VHS that way. They buy DVDs to put on their shelves and revisit.

WC: That’s very true.

[We both take sips of our hot drinks.]

WC: I’ll just check one more time to see that I’ve got it.

[Click]

WC: In The House of Science, you repeat the image of the woman rolling down the sandy hill many times, playing with it with different effects, reversing the motion, slowing the motion down, etc. I noticed that in many of your films you repeat certain key images. Could you please talk a bit about the significance of this choice?

LS: I’m interested in repetition but also with a certain kind of transformation. The woman rolling down the hill in The House of Science appears in many different manifestations.

[Lynne glances at the window.]

LS: Wow it is really raining outside. I just want you to remember that. [Laughs]

[The tape recorder loses its power over us for a moment as we turn and look through the windows of the café. It’s really raining.]

WC: [Chuckling] Yeah it is…

LS: Um…I was interested, in that case, in the woman rolling down the hill because I liked the idea of a person having contact with the earth. It kind of goes back to your question about Stan Brakhage and when you don’t want to touch the medium and when you do want to touch it, and how it gets changed, and I was talking about dust.

I was interested in her body and my body and your body and what our connection is to the earth, and so as we roll down a hill – in this case a sand dune – we’re leaving imprints of our body, like a fossil. We’re leaving some kind of shaping to the earth, and I was interested in that pure contact, that the skin touches the sand, and that there is this sensual experience. A lot of times we walk on top of the earth, but we don’t enter it. I feel that with sand we enter it and we leave marks.

In that case when I was shooting it I took a friend to Death Valley and I had my camera – my Bolex – and I said “I want to shoot you rolling down the hill.” And she said “Well, I’ll only let you do that if you take your clothes off too.” She wanted me to have the same experience, and it was transformational. Being in sand is like being in water…but it’s solid. So it was exciting, and it was different from…say…pornography, where the person behind the camera is less vulnerable. So that was one thing, and I repeated it because I wanted this sense of propelling – that the body was being continually propelled through the universe or along the surface of the earth, or through the film. It was a sort of transitional device in the film, and I wanted this suggestion of something being cyclical. She turns and turns and turns again and comes back cyclically in the film, and she is creating a cycle by rolling, so it has two aspects.

And then in Investigation of a Flame I have images of a flower that repeat…red flowers. So there’s a literal meaning for that and a more allegorical meaning. The literal meaning is that those flowers are red in that part of the country in May, during the spring, when the Catonsville Nine burned draft files with homemade napalm, and they did it May 17, 1968. I shot those images on May 17th, 2000 or something. I wanted to think about doing this drastic action…this illegal action…when the flowers were in full bloom, when spring was at its height. So I felt that by putting my body with the camera into this environment at this time of year, cyclically, decades later, I could know what was bursting around in the climate.

But then those flowers keep coming back no matter what…as long as global warming doesn’t destroy the earth…even if we’re sad, even if we’re at a war, even if conflict is right outside our door. The flowers still come back. That was interesting to me. I started to look at my images of the flowers where I shot them in this sort of speeding blurred way, and they started to have the feeling of blood to me. So sometimes you look at them literally as flowers, and sometimes in conjunction with the voiceovers talking about blood, they start to appear like blood.

WC: Right.

LS: So I wanted there to be that visual ambiguity. That happens sometimes when images are repeated. They have a literal meaning, and then they have something that goes outside that. And that’s what I hope to happen.

WC: In Photograph of Wind, you film your daughter, Maya, in a single, brief moment and use the abilities the medium to extend it. I used to take photographs all the time. Of myself, my friends, my family…I hope you don’t mind if I read the rest of this question from my paper because I wrote it out carefully.

LS: Yeah, sure.

WC: I think that I was hoping to capture the emotion of those moments, preserving them, hoping to look back on the photos someday and revisit that time in my life – feel what I felt then by looking at the photographs. A couple of years ago, I realized that it’s impossible for me to recreate life or truly capture moments, because they do not exist mutually exclusive of the moments before and after them. Like when I look back on photos of me and my mother and father before they got divorced, I know that things must’ve been happy then, but I don’t feel that happiness. I feel nothing but sadness. How do you feel about the ability or inability of film to capture the essence of a moment?

LS: That’s a really great question. I like that. Um…yeah I’m interested in the way that images, and family images in particular, mostly hide. They mostly conceal, rather than reveal. So in Photograph of Wind I’m kind of admitting that, because you can’t photograph wind. You only photograph what wind carries. You only photograph the effects of wind. But wind itself is not visible, so I suppose I was wondering about my daughter’s youth…whether she was visible to me in her essence, or was she visible to me in her physicality. And there’s this kind of…

[The waiter somehow appears next to our table and stands there awkwardly, oblivious that we are having a session of profound introspection and reflection.]

W: Order?

LS: We’re fine.

[The waiter leaves.]

LS: And that kind of connects to States of Unbelonging; this idea that we try to grasp something, but we can’t have it completely. We can only try to cherish the fragments, and Robert Frank, the photographer…do you know his work?

WC: No I don’t.

LS: He made a film, and I think he just casually used the expression Photograph of Wind, and I loved it. And I feel like that’s maybe what I’ve been doing my whole life: trying to photograph wind. So there’ll never be an absolute success. We’re always trying to grasp something that’s just a bit farther away than what we can really get a hold of. But that’s also a nice thing because if we grasped it, then we’d say, “Okay, the challenge is over.” So one of the reasons I went to film rather than photography, because I started photography too…or at least fancied myself a budding photographer, was that I was interested in…like you said before, the before and after…but I was also interested in the wisp…the wisp of something coming through: the…the motion. And it’s funny we call what we make, “moving images.” I was interested in things affecting us emotionally. So when we say “That was a very moving experience,” we don’t mean that we moved physically. We mean that we were touched emotionally, so that play on words is probably one of the reasons why we were drawn to twenty-four frames per second instead of one frame per second. [Laughs]

WC: [Laughs] Oh I should check the time.

LS: We’ll get the check.

WC: Sure. It’s 9:25.

LS: Okay. Well we’ll do…is one more question okay?

WC: Alright.

LS: [To waiter] Can we have the check please?

[I’ve got one last shot. I pause for a moment and look through my questions to pick the best one to ask.]

W: Five-fifty.

WC: I’ll get it.

LS: Are you sure?

WC: Of course.

[I hand the waiter six dollars]

WC: Okay so…the last question I guess…would be…um…Could you please talk a bit about your use of superimposition and collage in your films?

LS: Yeah. I would say my interest in super…or my attraction to superimposition… comes from the collage. It comes from the fact that I made collages way before I made films. The thing about collages is that there’s no transparency, right? So it’s kind of a fascinating outgrowth of the motion picture…the video or film mode of production…that we can produce transparency. Through the transparencies I think that you can create a level of abstraction which is really key to my work: that my viewer doesn’t experience or witness images always in their literal presence, but they become abstracted, and in that abstraction, they become more associative and more freeing intellectually. And that only happens in the viewing experience.

In fact, for me, the transparencies, or the multiple exposures, remain discreet in my films. They only become connected by you. And once you do that, there’s this kind of energy and invitation for you to create new meaning. Like I have my own ideas of what the meanings are, but they might not be the same as yours. I think I’m guiding you to thinking about the images in a new way, and that’s exciting to me, once the images create a kind of language that’s very…image based. You might even say, “I can’t put it into words, but this happened, because these two images were superimposed and that made me think in a new way, and I had this…what Roland Barthes says is this ‘punctum,’” which is NOT a literal interpretation. It has to do your thinking, “Oh, I see something new. I see a relationship that I didn’t see before.” And it just kind of gets you like…new dessert… [Laughs] “Ooooh that is delightful!”… in my imagination as a viewer, or your imagination.

So I like that. I like to delight people. I am in the entertainment business right? I like to delight people visually, and then it makes you think in new ways. That’s probably the place where experimental film is a little different from traditional film. Because we don’t always have the control of that mode of interpretation, and we like that lack of control and we like giving the viewer this ability or this chance to be delighted intellectually without our knowing exactly how that will happen. [Laughs]

[One of the main things I noticed about Lynne’s films is her use of multiple exposures, superimpositions, and dissolves. Often the images did not have any apparent meaning to me. In House of Science, for example, I wasn’t sure about the overt meaning of showing the woman rolling down the hill over and over again, with the image altered and superimposed against various images.

With Lynne’s films in general, I can appreciate the narrative arcs. The part that fascinates me the most about her work, however, is not the surface meaning, but rather her ability, through her sound design and her selection of images to make me distinctly feel a certain way. The parts of her films that leave the strongest mark in my mind are those moments of abstraction that elicit emotions or feelings from me. This freeing of the mind that Lynne talks about with regards to how we openly and personally create meanings for abstract images is interesting and compelling to me.]

WC: Okay great! I think that’s a nice place to end the interview. Thank you so mu…

[The tape cuts out]

9:35 AM

I thank Lynne for lending me her time and her sincerity. Rising from our seats and taking out our umbrellas again, we head out into the drizzling rain. I put my tape recorder in my bag and hope that the interview recorded properly. She walks me to the subway and we go our separate ways – she to her home where her family awaits, and I to my place where I assume my girlfriend is still asleep. I feel like I’ve been awake for hours and the day is nearing its end…and yet, it has barely begun. My entire morning feels surreal.

The whole subway ride home, all I can think about is Lynne’s Photograph of Wind and what she said about how with film, we are grasping at the intangible, trying to capture what cannot truly be captured. I wrote an essay last year called Second Glances, in which I dealt with my desire to preserve moments and feelings in still images so that I can revisit them at a later stage in my life and remember the way I felt at the moment the photographs were taken. The conclusion that I came to at the end of my essay was that taking photographs was a futile effort because I could not capture the essence of moments in my life. The emotions I feel when looking at photographs are constantly tainted by the progressions in my life. I never see a photograph in the same way twice.

Watching Photograph of Wind and talking to Lynne about it, my faith in photography has been rekindled. Maybe it is all about the pursuit of capturing and reproducing reality. Perhaps it doesn’t matter that we can never reach that goal.

We cannot see wind, but we can see it rustling the leaves on a tree, tossing a girl’s long hair as she stands in the open, carrying pieces of debris through the air, making them dance. Similarly, we can never experience the past – it has gone and we have all changed…but through photographs and motion pictures, we can hope to catch glimpses of it, and perhaps that is enough.