Wide Angle Volume 14, published in 1992. The House of Science: Museum of False Facts / Feminist Polemics through Film Poetry by Marilyn Fabe.

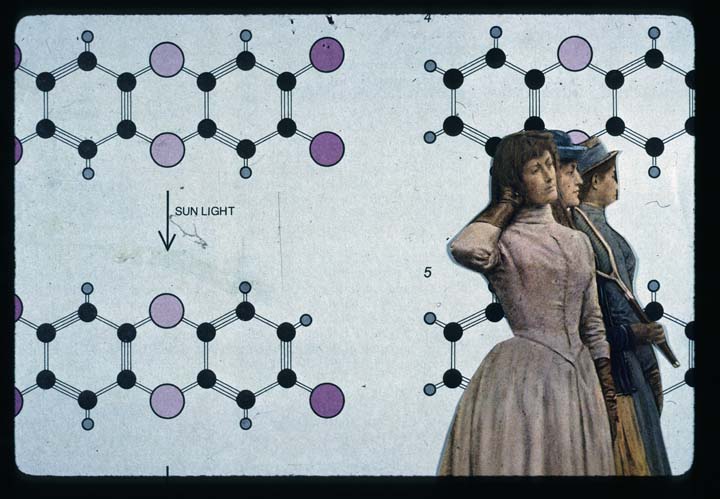

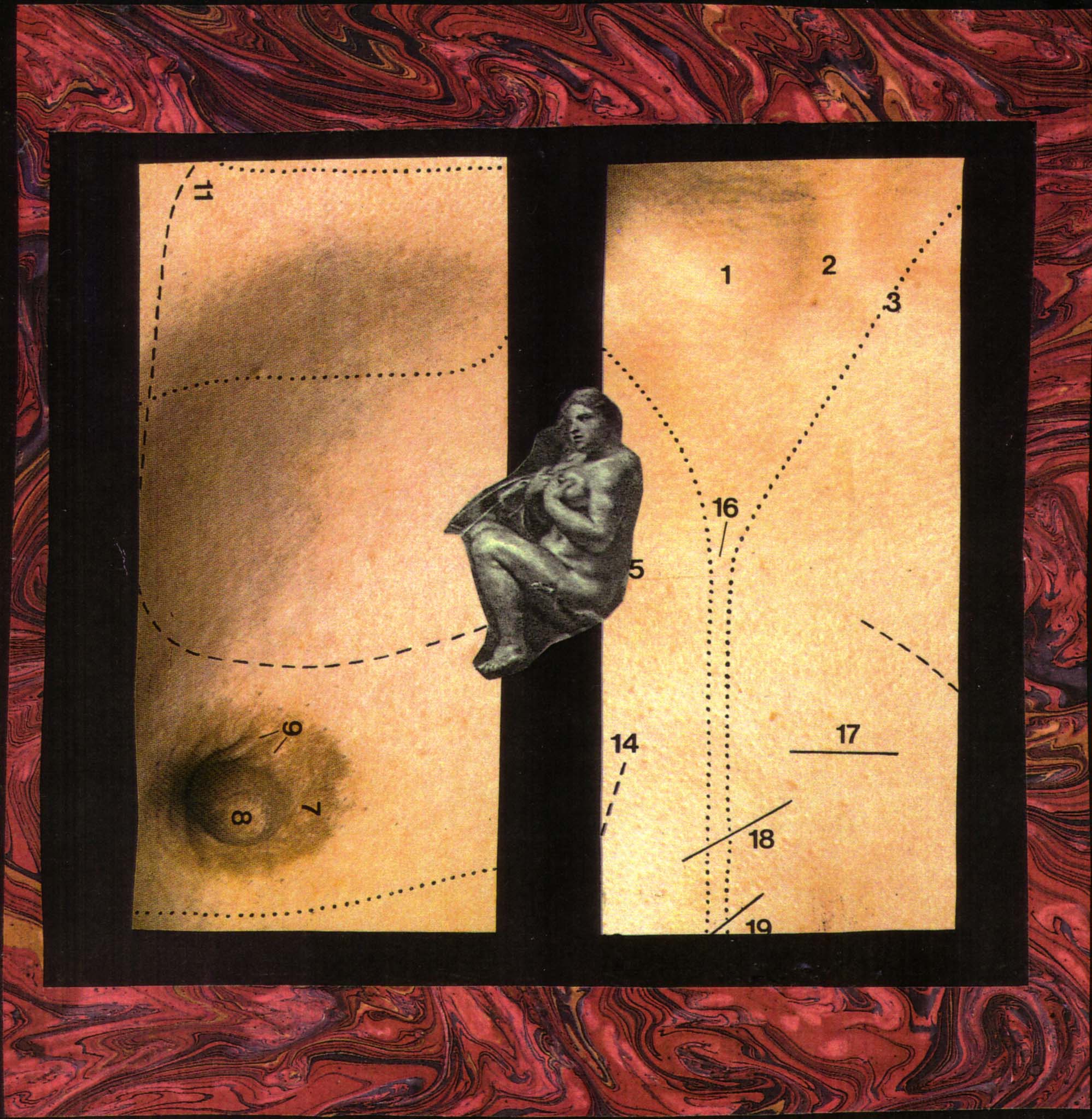

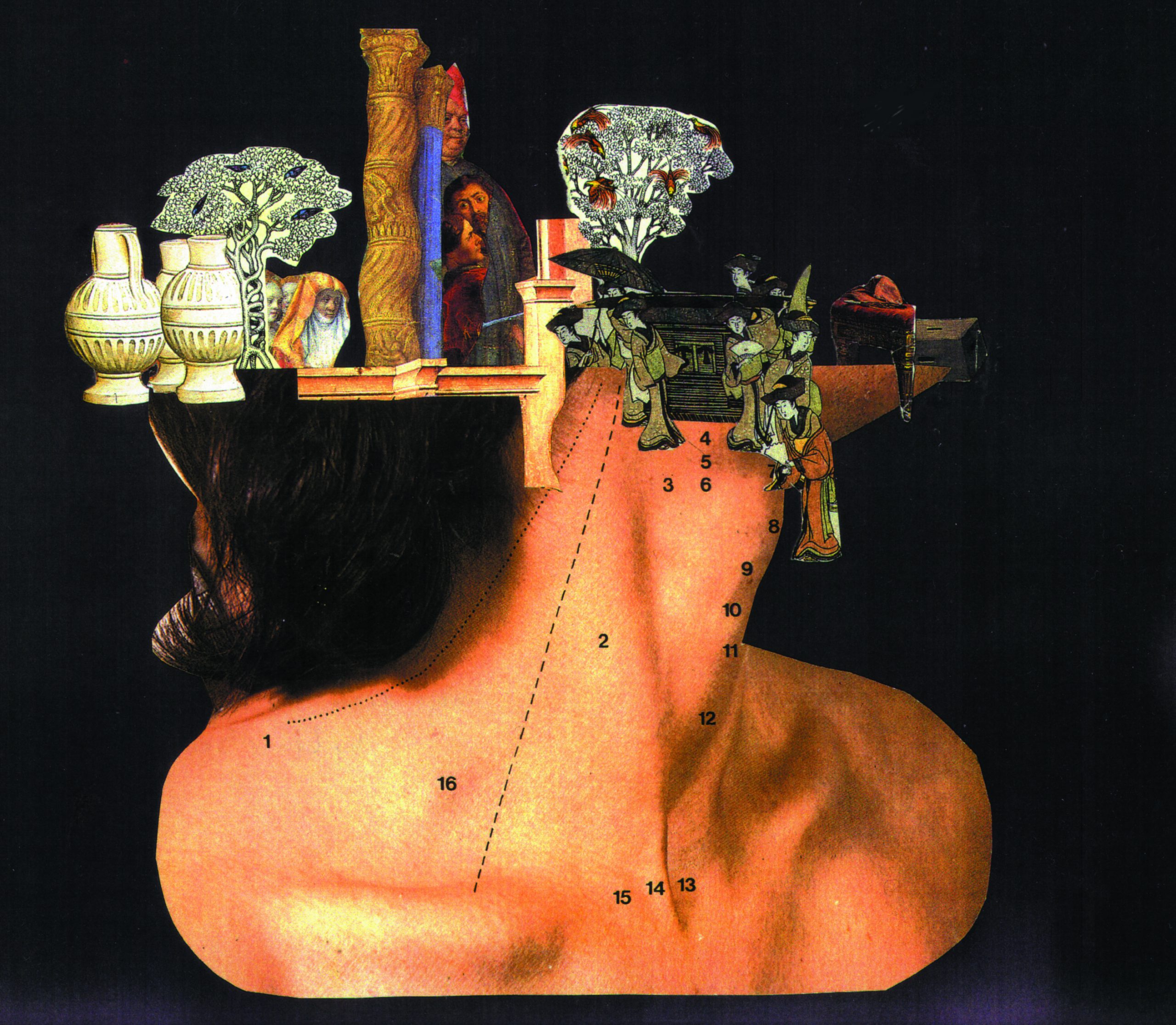

In The House of Science:A Museum of False Facts, Lynne Sachs exposes the edifice of scientific “facts” with which the male-dominated disciplines of science and medicine have constructed an image of what a woman is. Through-out the 30-minute film, Sachs traces the unfortunate interface between women and science, a terrain in which men are supposed to have all the knowledge, defining and mapping out women as their territory, while women are alienated from their own bodies.

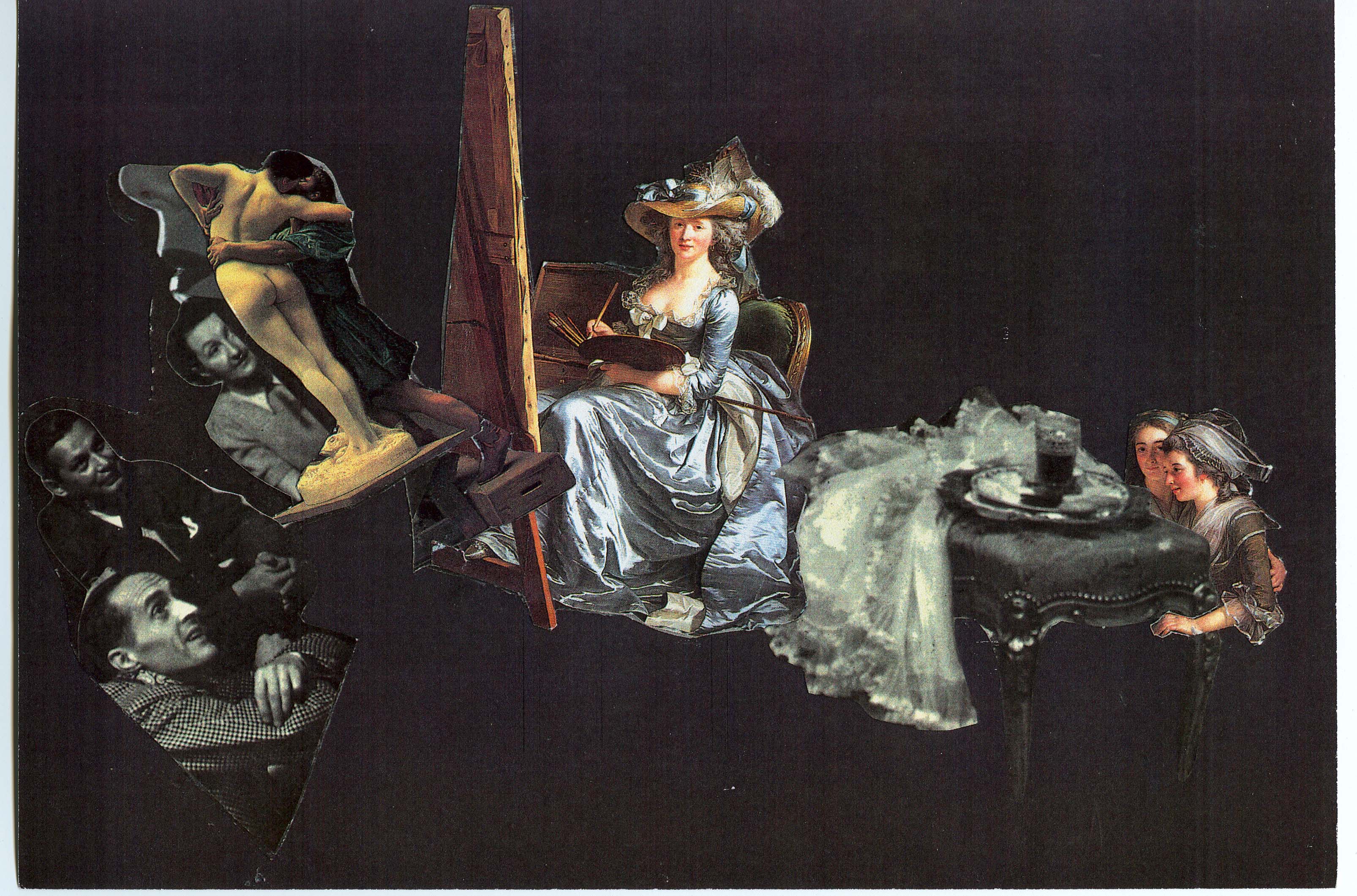

This synopsis of the film’s thesis doesn’t begin to convey the wit, complexity and visual brilliance with which Sachs approaches her subject. Indeed, I would argue that she achieves in this film what Sergei Eisenstein sought through intellectual montage: “to restore to the intellectual process its fire and passion … to give back to emasculated theoretical formulas the rich exuberance of life-felt forms.” Through associative montage, superimposed collage, and sound in counterpoint to image, she launches an attack on the presumed objectivity of western science, and exposes the limitations of verbal language in expressing “the truth.” Sachs does this by replacing the language of logic and science with a complex film poetry. The House of Science is a passionate feminist film that makes its point through poetry rather than polemics.

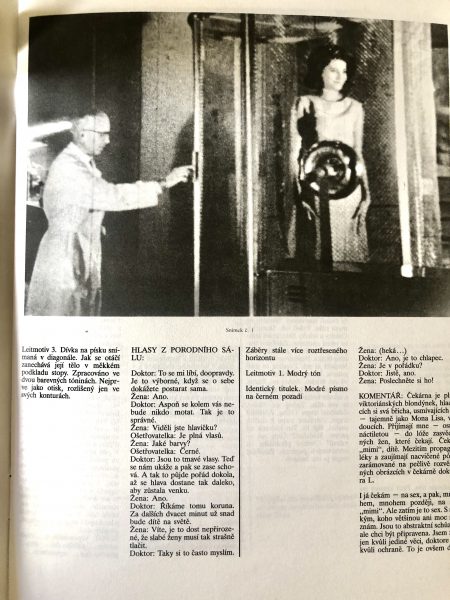

Even as Sachs depicts the house of science into which women have been locked, she subtly and subversively dismantles it-or, in a metaphor more appropriate to the film’s denouement, burns it down. The manner in which the first sequence works suggests the structure of the film as a whole. Before the titles appear, Sachs counterpoints found footage of a man in a white jacket-a Doctor with a capital 0-escorting a woman into a glass booth. This image is accompanied by a voiceover of a woman describ- ing the cold, perfunctory manner in which she was treated during her pregnancy by her gynecologist. Here the disparate sound and image tracks uncannily mesh, the glass booth becoming a symbol of the sterile House of Sci- ence in which women have been enclosed, objectified and observed. At the same time, the voice of the woman reflecting on her pregnancy reminds us that everyone’s original dwelling is the woman’s body. In a flash of recognition an idea bursts forth: because men come from a mysterious house (the womb), they have a compulsive

need to put women back into one (the doctor leading the woman into the glass booth). The sadistic implications of this are played out associatively when the same doctor detonates a fuse which causes a model of a house to burst into flames. Sachs adds her own heat (her anger) to this image by tinting the black and white image of the burning house with flashes of orange.

This foregrounding of the filmmaker’s feelings, superim- posed in color on the black and white image, resonates suggestively with the pregnant woman’s description of her gynecologist: “He always struck me as short, cold and with glasses and he may not look like that at all.” At issue here is the questioning of any kind of objective reality. Unlike the authoritarian certainty with which men speak throughout the film, this woman acknowledges how feelings filter our perceptions of reality.

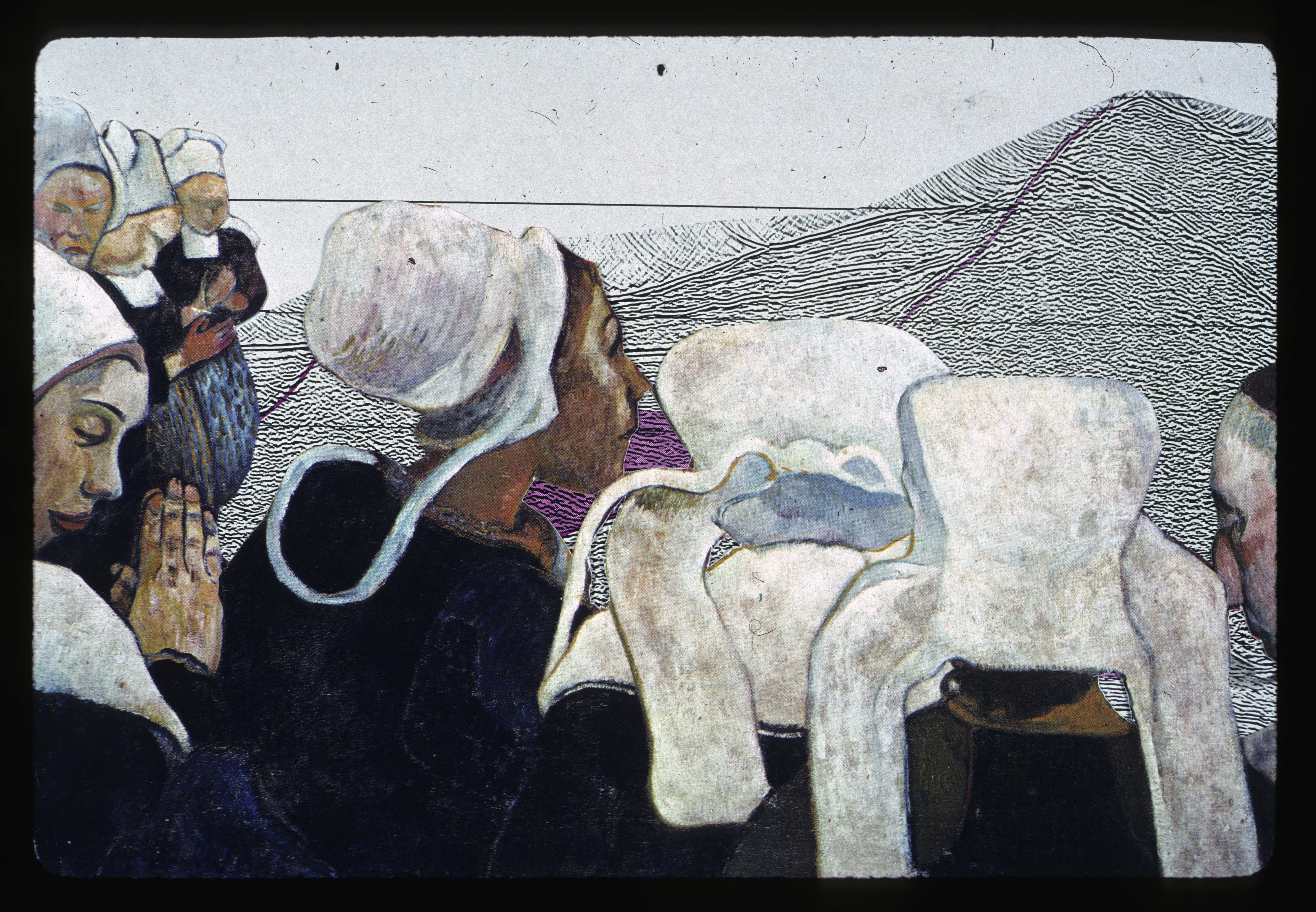

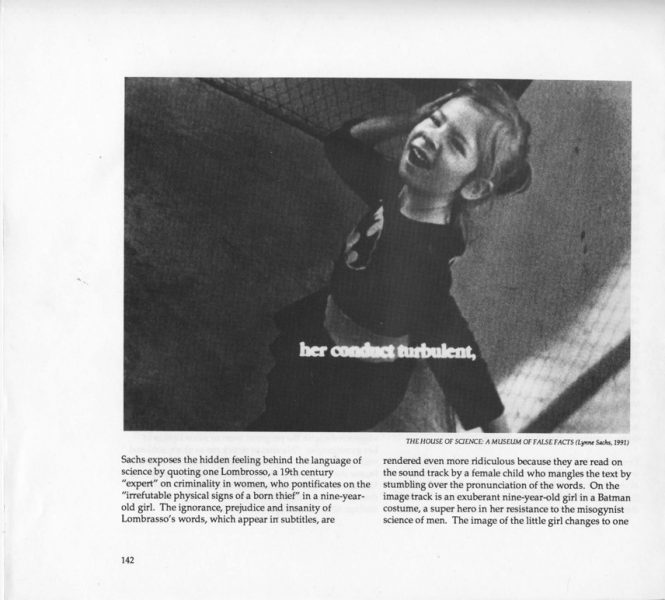

Sachs exposes the hidden feeling behind the language of science by quoting one Lombroso, a 19th century “expert” on criminality in women, who pontificates on the “irrefutable physical signs of a born thief” in a nine-year- old girl. The ignorance, prejudice and insanity of Lombrasso’s words, which appear irr subtitles, are rendered even more ridiculous because they are read on the soundtrack by a female child who mangles the text by stumbling over the pronunciation of the words. On the image track is an exuberant nine-year-old girl in a Batman costume, a superhero in her resistance to the misogynist science of men. The image of the little girl changes to one of a dancing woman, who, unlike the child, is not free but contained in a crudely chalk-drawn frame of a house, reminding us of how adult women lose the liberty of girlhood only to be confined in the constrictive House of Science.

Sachs places frames around men as well, play- fully asserting the power of the woman artist to turn the tables. In one instance a man stands before a picture frame lecturing on anatomy. As he discusses the framework of the body, he himself appears in a frame, and the prurience underlying his pompous abstractions is exposed when the picture in the frame within a frame turns into a nude woman.

As the film progresses, Sachs increasingly presents images of women defining themselves. Three adult women, who earlier had dutifully mouthed Lombrasso’s certainty that female thieves and “above all prostitutes” have a cranial capacity inferior to that of “moral women,” begin to speak for themselves. For example, a woman art critic offers insight into why the pubic hair was removed from Renaissance representations of Venuses: ”fhe more the visual image can be disarmed the better the male artist feels.” And the filmmaker’s journal entry expresses the exhilaration and power of a woman with a speculum looking into herself.

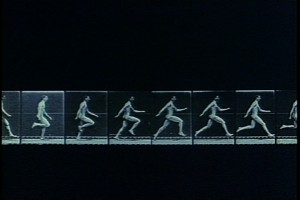

Yet Sachs offers no smug sense of victory for women. The latter images in the film, like those at the beginning, are riddled with ambiguity. The woman with the speculum lives in dread of the cancer she might find now that she has the power to examine herself. And little girls, who through- out the film resist the confinements of their culture, are given the gaze-they become spectators in movie houses-only to witness hauntingly beautiful images of graceful south sea island women spoiled by a sexist and racist voice-of-god commentary.

Although Sachs does not posit any material or transcen- dent victory for women, her film does offer a model of witty, exuberant, sensual and subversive film language that questions and subverts the patriarchal structures of thought and representation that for centuries have impris- oned women. Thus, at the end of the film the blazing house reappears, but now it takes on a new meaning: the fire that bursts forth and collapses the walls of the house becomes a powerful metaphor for the incendiary power of the woman poet/polemicist to destroy from within the oppressive structure of the House of Science.

Marilyn Fabe teaches Film Studies and Women’s Studies At the UniversityofCalifornia-Berkeley. She is The Co-author Against theClock:Career Women Speak on the Choice to Have Children (RandomHouse, 1979).