Alex Fields

June 7, 2024

https://notreconciled.substack.com/p/lynne-sachs-from-the-outside-in

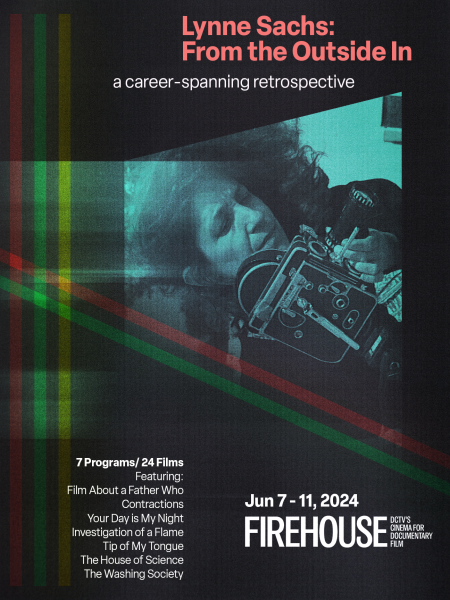

For forty years, Lynne Sachs has produced adventurous work at the intersection of documentary, essay, and avant garde film. Though they vary greatly in form, all of her films seek novel ways of questioning dominant perceptions of gender, work, and artistic representation. A career-spanning retrospective of her work, From the Outside In, screens this weekend (June 7-11) at DCTV in New York City and includes approximately two dozen films, from the early 80s to brand new films.

The earliest of these films are interested in our gendered perception of the movements of human bodies. The strongest of these, Drawn and Quartered (1986), uses 8mm film stock in a 16mm projector to display a “split” screen of four frames on one reel of celluloid. The top and bottom rows are identical, but the left and right show difference scenes, initially with a man on the left and a woman on the right. The figures, both naked, engage in a series of ordinary activities: squatting and standing, speaking and gesturing. The quadruple frame, along with the film’s silence, create a choice and push the audience into awareness of where we direct our attention, including how we may interpret the man’s and woman’s body language differently despite their essential similarity.

Other early films employ different devices toward comparable ends. Still Life with Woman and Four Objects (1986) films a woman putting on a coat, peeling an avocado, and so on, but adds a soundtrack seemingly unrelated to the images. A voiceover reads what sounds like a screenplay–“Scene 1. Woman steps off curb and crosses street”–but these actions never occur on screen. Similarly, Fossil (1986) cuts back and forth between video of women performing modern dance and women in a Balinese village working along a river. Both films break down barriers between what we perceive to be scripted performances of art and what we perceive to be mundane performances of work.

Over the following decades, Sachs’s work expanded this interest in representation into an examination of scientific and medical literature. One of her most ambitious and complex works, The House of Science: A Museum of False Facts (1991) assembles a whirlwind collage of texts and images dealing with (pseudo)scientific accounts of women’s physiology and and women’s experience in medical contexts. Women’s efforts to speak for themselves–in poetic written memories or seemingly documentary audio records–are interspersed with supposed expertise speaking for and about them, from Renaissance art to images from science books and documentaries. The sheer variety of source material, combined with the fact that images and sound rarely match, means that the materials are never able to settle into a clear narrative, and instead are presented in their character as representations. The overall effect mimics something of the confusion of a lifetime of contradictions taught to women as demeaning frameworks for understanding their own bodies, with the clarity of lived experience struggling to emerge from among this morass. This is sometimes played as comedy, such as when the laughter of children is played over a patently stupid text describing women’s brains and criminal tendencies.

Questions of meaning and textual representation get a much darker and less playful treatment in The Task of the Translator (2010), named for Walter Benjamin’s essay of the same name. Sachs is arguably less concerned with the problems of translation between two written languages and more so with how one appropriately translates the horrors of war into a journalistic text or art work. In the film’s first section, the voice of a doctor describes the work he did during a war to preserve and present human remains while we watch footage of kids at play. In the second section, scholars sit around a table translating a horrifying article about burials in the Iraq War into Latin. In the third and final section, a radio report describes a woman’s effort to recover the remains of her husband who died in the war, while a laundry machine spins on screen. All of these segments pose an unanswerable question about how the meaning of these wartime texts can possibly be grasped by their intended audience living in an utterly different context.

In a very different way, A Month of Single Frames (2019) also deals with the idea of translation, this time between two artists. A posthumous collaboration between Sachs and Barbara Hammer, the film incorporates reels from an uncompleted 90s work by Hammer with new footage and audio recordings by Sachs. Hammer speaks through her own voice and through her work, and Sachs is implicitly in dialogue through her editing and her own footage. It’s partly a documentary, partly a completion of a once abandoned project, but its real magic is in the present tense interaction of these elements.

Sachs seems drawn to these ambiguous and open-ended forms, even in her more apparently conventional documentary work. Your Day Is My Night (2014) portrays residents in a Chinatown apartment who take turns using the same beds according to their different work shifts. The scenes are poignant, so much so that they begin to feel too perfect, raising the question of how scripted some of this might be, particularly when new characters arrive and introduce themselves without ever noticing the camera. Later in the film it becomes clear that the action is partly staged, even explicitly revealing the set as a literal stage. The film was created collaboratively with its actor-participants, who played versions of themselves and other actual interview subjects in both live and filmed performances, blurring the already soft lines between documentary reenactment and scripted fiction. The film itself emerges as only one document of a process which was, arguably, a more expansive art work in its own right. It therefore frames itself as a contingent and partial view, as interested in the political nature of representation and translated meaning as in the specificity of its subject, raising more questions than it attempts to answer.

See also this interview with Sachs published by my friends at Ultra Dogme.